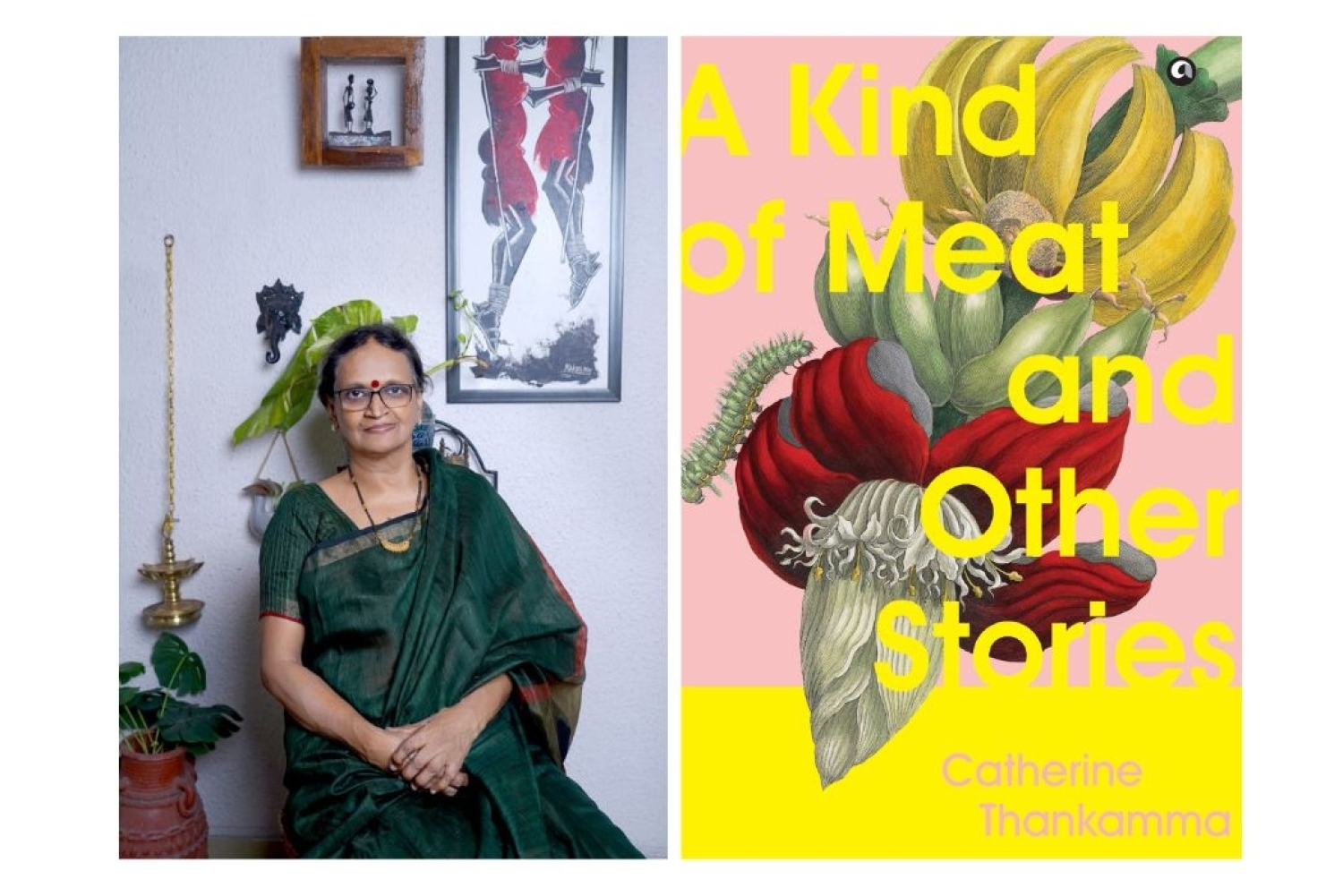

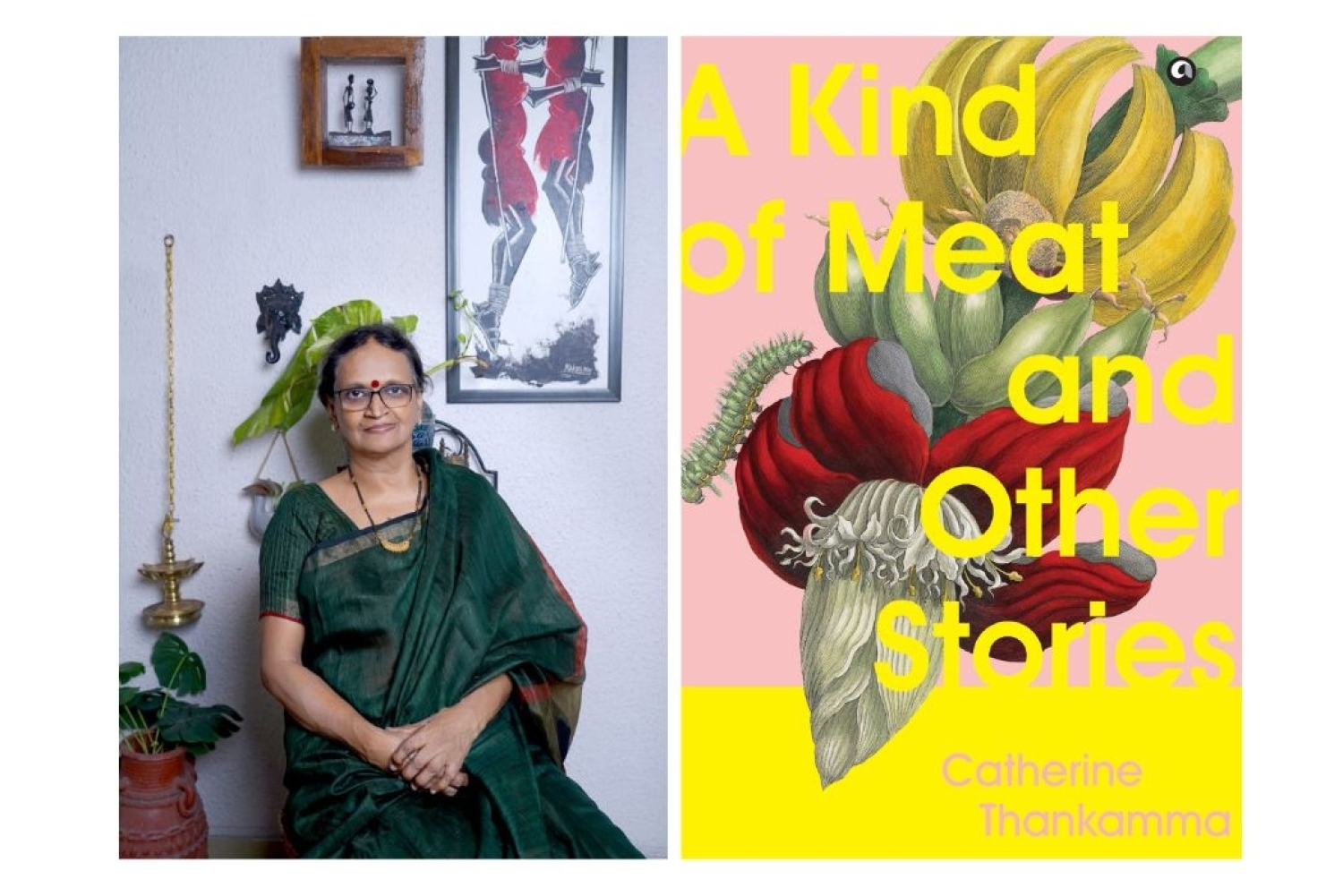

The stories in A Kind of Meat and Other Stories by Catherine Thankamma travel through some of the most quietly devastating corners of everyday life. One story looks at the subtleties of caste through a woman who is treated like an outcast despite being the chief polling officer. Another lets us witness how women can often become the strictest gatekeepers of patriarchy. Elsewhere, themes like modern parenting, education systems, and friendships fractured by communal divides take centre stage. There are stories about death and ageing too, where grief, silence, and the idea of home are gently prodded. We’re in conversation with the author about her debut short story collection.

The Collection

I've always been fascinated by the format of the short story because it's very focus-driven. It addresses just a single theme, and whatever happens, all the extras, whether they're characters or episodes, circle that central focal point, which makes it extremely powerful. This collection has twenty short stories written over a while. I wanted to stress people, incidents, particularly those who are sidelined, the unseen presences. Sometimes marginalization is deliberate. Sometimes it's accidental because they are not important enough to be considered relevant.

In a way, this collection is a celebration of womanhood. All the protagonists are women. The stories become more focused as they go on — about belief systems, conditioning, societal and familial structures, religion, and patriarchy. These stories try to hold space for what doesn’t always get said in dominant narratives.

Inspirations & Themes

I'm an introvert. I don't talk much, and I'm very happy being an introvert. I like to watch people. When you're interested in watching people, you notice interactions, sometimes just a fleeting scene. These things strike you. And short stories are the best way to capture that. It's the shortest, most impactful form. These moments would be lost in a novel.

Some of the stories come from things I’ve witnessed or felt deeply. For example, Ellunda is about a toxic family situation. A Kind of Meat is about a little girl, five or six years old, living in a rented house. The landlady asks her if her family eats beef. The child, overwhelmed and wanting to appear grown-up, says yes, and it spirals. The final sentence of that story is: ‘What is meat?’ That question stays. The lady is not cruel, but her rigidity and inherited attitudes shape how she reacts.

Then, there are stories about learning disabilities, about the education system. Since I was a teacher, that matters to me. There's one about narcissistic parenting, and others about how our belief systems shape our lives in ways we often don't see until it's too late.

“For me, writing is a way of processing, a kind of catharsis. It lets me sit with the ache and turn it into something that might resonate with someone else. ”

Shifting from Translation to Writing

Translation actually came second. I always used to write. Initially, I published a few short stories. One in this collection, Blood Sacrifice, was published by The Little Magazine in 1999. I’ve rewritten it many times since, so it’s quite different now. I’ve contributed stories to the Times of India as well, and I used to write in both Malayalam and English.

When you’re translating, you are controlled by the source language. You’re tied up by the text. The challenge lies in finding the exact equivalent, the right word, the tone, the rhythm, the subtext. For instance, translating N.S. Madhavan, who writes in a symbolic, poetic style, is very linguistically exciting. In contrast, translating Narayan’s Kocharethi, the first novel by an Adivasi author, required simplifying and adapting my English to suit his stark language. It was equally challenging.

I eventually stopped writing in Malayalam because I learned it as a second language. English is my mother tongue: I was born and brought up in North India. So for the kind of writing I wanted to do, especially stories that include literary references, quotes, and that kind of density, English gave me more space.

On Contributing to Regional Literature from Kerala

I think my stories will be quite different from the general stories coming out of Kerala. Stories tend to get typecast, and often it’s the Hindu upper caste narrative that dominates. Certain lifestyles and cultural settings become overrepresented. Christian middle-class or Syrian Christian perspectives aren’t seen much. Not that I’ve confined myself to that either, the stories span a wide range, but I do feel this collection fills that gap. These are not conventional subjects. They’re drawn from life, from things that ache within you and that you carry forward by turning them into fiction.

The Future

For me, writing is a way of processing, a kind of catharsis. It lets me sit with the ache and turn it into something that might resonate with someone else. So, I’ll keep doing that, in whatever way I can.

This article is part of our monthly digital capsule, EZ. Read the EZ here.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 17-9-2025