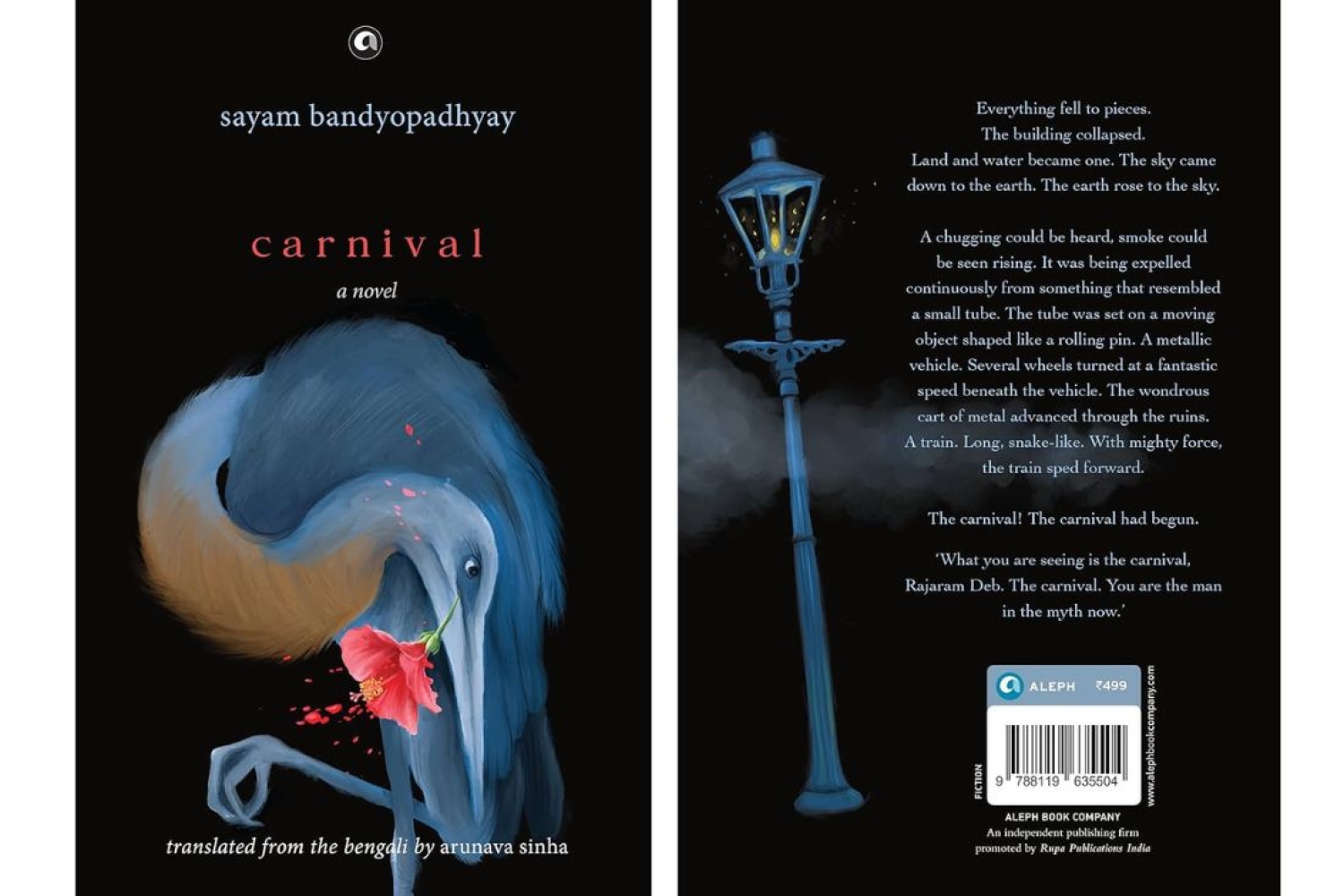

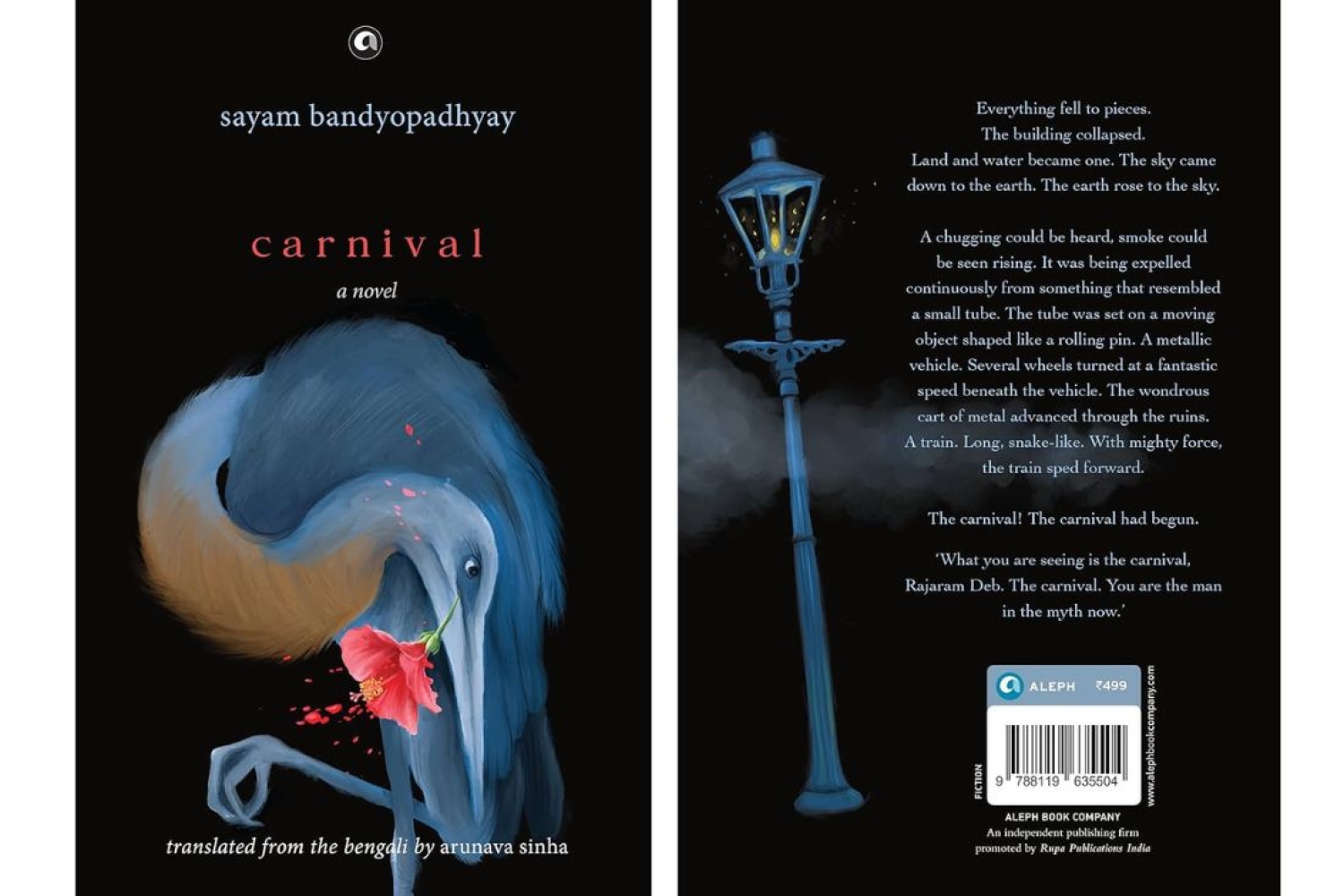

Carnival by Sayam Bandyopadhyay, translated by Arunava Sinha is a novel whose essence remains embedded in colonial Calcutta. It is the perfect blend of mysticism and realism, hence creating a narrative that blurs the lines between the past and the present; fiction and truth. Rajaram Deb, the protagonist of the novel, chases a transcendental celebration, around which the plot of the story unfolds. We’re in conversation with Arunava Sinha, the translator.

How do you choose the kind of work you translate – what is it about Sayam Bandyopadhyay’s Carnival that made you want to translate the original into English?

Increasingly, I look for a text that does something new—it could be a set of new ideas, a completely new way of telling a story, a new way to use language, a new way to depict people and what happenes to them. This is what made me try Carnival. It does all of these things, and in an intense, concentrated manner. This novel is slim only in terms of the number of pages. In every other way it is rich.

Regional languages such as Bengali have always cultivated space for surreal imagery and elements – how do you ensure that this cultural context remains in the translation as well?

As always, I am led by the text. The context, the culture, the perspectives, are all contained in the text. Every reader will come to a text with their own knowledge apparatus, you cannot make any assumptions of knowledge. So I try to put in my translation what the text is telling me, but I do not attempt to provide additional information. A well-written book always overcomes the challenge of context. As for elements like surrealism, I don’t think that’s confined to particular languages.

What is it about Rajaram Deb, the protagonist of this novel, that drew you to him? As a translator, do you find it helpful to get into the minds of your characters?

I am more intrigued by Rajaram Deb than being drawn to him. He is a classic example of a member of the indolent classes of 19th Century Bengal, but the conflict within him comes from his yearning for something more than the luxurious life of a zamindar. He seeks something, he doesn’t know what it might be. This impulse, set within the framework of colonisation, makes him a most unusual figure. He also seems to have adopted some of the traits of the protagonists of existentialist novels, even though he has no idea what the philosophy of existentialist might be. In fact he is not an intellectual. But his mind is always in motion, and he has a tremendous imagination.

As somebody who teaches translation, and facilitates the translation of many regional languages into English, what makes a good translation?

A good translation is a great book to read. The relationship between the translated text and the first version cannot be benchmarked to standardised parameters of excellence. But you could say, for a translation from Bengali into English, for instance, that a good translation will be a terrific book in English that clearly did not begin life in English, that stretches the English language, that conjures up another world that the reader can travel in effortlessly.

We’d love to hear about your journey as a translator — how did you enter this field? What are its best parts, what are some not-so-best parts?

Like most translators, I began by accident, just trying my hand at it, much like humming a song that you like. Then opportunities came, and more opportunities, and there was no looking back. The best thing is being able to read deeply and closely and write creatively but with constraints—the text exists already, you cannot write your own—which is an experience I’d recommend to anyone who likes writing.

What are you working on at the moment — what’s the future looking like?

There’s a series of books waiting to be translated. Magnificent books, really. But right now I’m finishing up a mammoth anthology of Bengali writing which will have the works of more than 100 writers—and I couldn’t be more excited.

Words Neerja Srinivasan

Date 02.08.2024