Unconventional and experimental in his storytelling, Jeet Thayil is unafraid of playing with structure, words and/or plot. Every piece of his writing, be it poetry or prose, is crafted organically. His writing is poetic and piercing, and it takes you on a trip that is rapturous and exhilarating.

I interviewed Jeet twelve years ago when he had just released his debut book. Narcopolis was not just a read, it was an experience. It was provocative, intriguing, compelling, but above all fascinating. Since then, up until now, I have followed Jeet’s work closely. His relationship with writing can be felt through the worlds and characters he creates from his imagination and his reality. Writing has shaped who he is today and has helped him stay away from ‘rehab or jail or a career as some sort of international criminal. It’s the only thing that stands between me and a kind of encroaching darkness that encroaches on us all. It’s the one thing that pushes back and gives you some control over time, vanquishes time, annihilates time, stops time. For me, that happens only when I’m immersed in a poem or a piece of fiction’.

Out now with a new book of poems, The City under the City, his first ever collaboration, and his genre-bending novel The Elsewhereans, Jeet took me through his process behind the making of these books, and his relationship with writing.

Can you tell us about your new book of poems - The City under the City?

The book is a collaboration with the Australian poet, John Kinsella, who has published more than seventy books in his lifetime, and he’s only sixty-something. He’s very focused and just a brilliant poet. We sent poems to each other over two years, poems that circled around the cities of the world. He would send a poem, and I would send one back. Sometimes our responses took off at a tangent, and sometimes they’re very specifically in reply to what came before. Through this prolonged interaction, we discovered connections between us that we didn’t know existed. Addiction, for instance.

Was The City under the City a planned project, or was it organically created?

I met John once in New York many years ago. I went to a reading by him and I was struck by his approach. He didn’t sit on a chair and read, or stand at a podium and read, the way most poets do. He walked around the room, around and into the audience. He had memorised some poems, and some he read from a book, walking fast. I remember he had an electric presence. He teaches in the US and the UK, and lives often in Australia. He thinks of himself as an Australian poet, but is very clearly a poet of the world, who has lived everywhere, including India. He sent me an email out of the blue one day. It was during the pandemic, asking if I’d like to collaborate on a book of poems. It took me about five minutes to say yes. So, he sent the first poem, and it took maybe a week for me to send a reply. The thing about John is, you send him a reply and sometimes within hours he responds with a poem. I felt like a bit of a slacker. And it’s not like he doesn’t have other things going on. So, very often, his replies would come the same day, or the next day. And then I would take a week, a couple of weeks. Sometimes I’d take just a day or two, inspired by how fast he was. At the end of it, when we were sent the proofs, we carried out minimal edits. The joy was in the spontaneity, how organic it was, and how little we changed the original versions.

And how long did it take you, when did you realise it’s time to end?

By the time we were about a hundred or so poems into it, we realised, this was it. Then he sent one more, and I sent the last poem, which turned out to be a ghazal. In the ghazal form, the poet puts his name into the last couplet, so in the last couplet, I put ‘J and J’.

So, two years of communication back and forth. And in the midst of all that, did you meet each other?

Never. But the thing is, in one of the poems, he says something about strangers. And in my reply, I write, we are not strangers. Because at this point, it feels like we’re friends, although we’ve never met. A week after this book ended, John sent an email saying, Shall we start another? We are now amid a prose poem collaboration.

This is your first collaboration. How has the experience been?

There’s nothing like getting an instant response to a poem and framing it in your head and responding in your turn; it’s been a pleasure and a joy. The great thing about John is that he doesn’t overthink. It’s uncanny. When you read those poems, you’d never think they were written in a matter of hours.

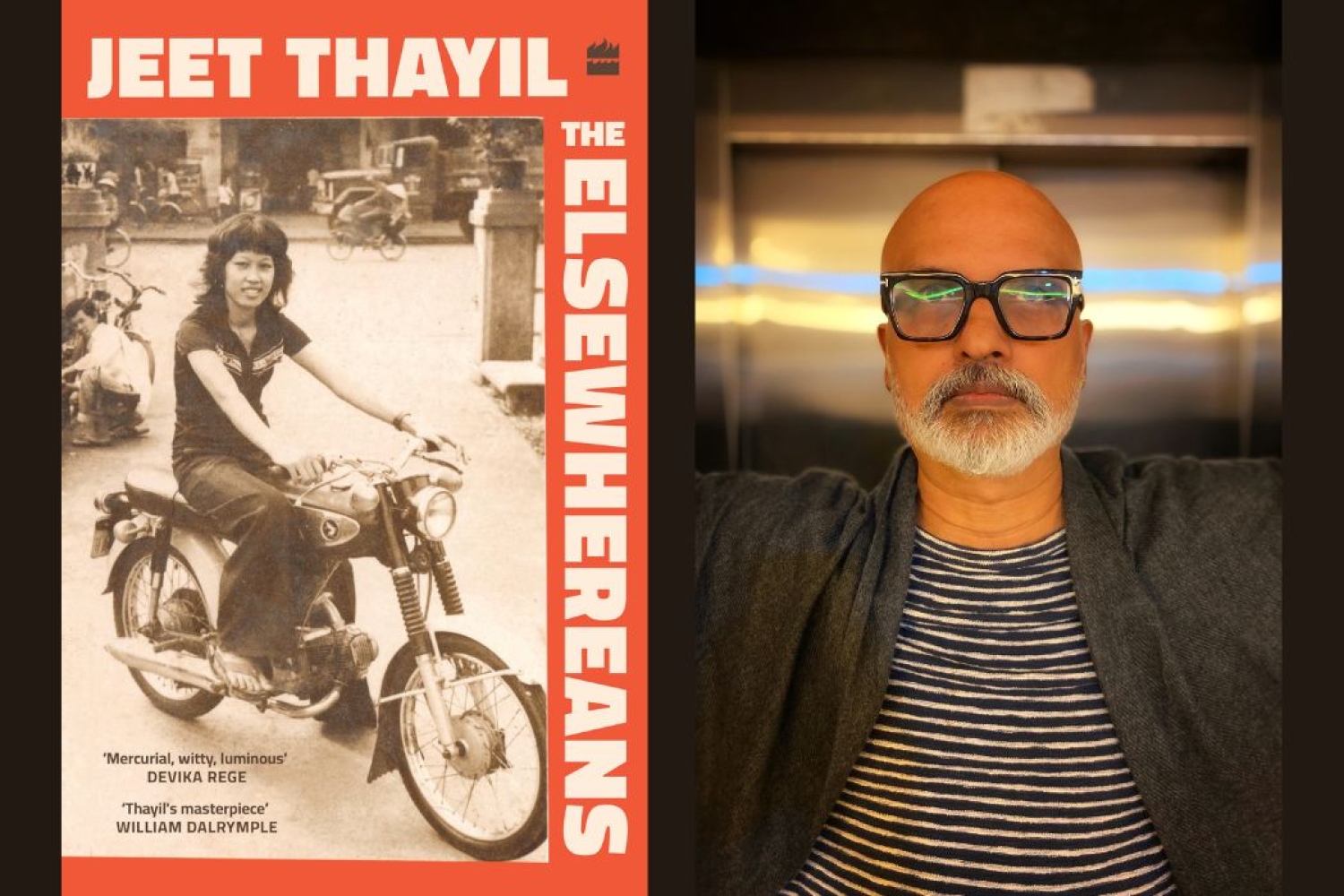

From poetry to a book that is clearly genre-bending—art memoir, art fiction, art non-fiction, art travelogue, and art photography—can you tell me a little bit about your forthcoming book The Elsewhereans?

I think genre-defying is not an exaggeration. What I’ve done is, I’ve used actual photos, of, for example, my parents and their life stories, the events that happened to them, the travels they undertook, the many houses they moved in and out of. The moment when my father was arrested by the chief minister of Bihar because he was editing a newspaper, The Searchlight, and he took the side of the student protesters. The chief minister threw him in jail. It was the first time a journalist had been arrested for sedition in Independent India. There’s a family photo of him coming out of Hazaribagh Central Prison. Of course, he treated it as a photo op; he was wearing a suit, and he’d groomed his beard. My mom, on the other hand, is wearing an informal chiffon sari draped around her shoulders, holding flowers, and she looks distressed. I use that photo in the book, and I use their names, but the story around it is mostly fiction. So yeah, there are real pictures and there are fictional pictures that are used as if they’re real pictures. The reader won’t know where the fiction ends and the fact begins.

I had to ask my parents’ permission to do this because there are some unexpected trajectories to the story, including imaginative leaps they might not have enjoyed.

What an interesting approach - what inspired you to write this and what inspired you to take this format?

I’ve always wanted to write a family history but I didn’t want to write a conventional memoir. There are ways a conventional memoir can be treated interestingly. For example, Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton, a memoir that is turned into something that borders on literary fiction. I wanted to write a memoir that transcended the genre of memoir, and I realised the only way of doing that was to use historical material as a set of building blocks, to use real events, fraught moments in history, for example, the fall of Vietnam, the liberation of Hong Kong, the subjugation of Hong Kong, the Second World War, there’s a chapter set in Germany, a chapter set in China. All of these historical events are building blocks set in real time, based around actual characters whose names I might have altered or not. I thought it was a way to make it interesting and to take some risks as well, because this is a risky project.

You’re going from Vietnam to China to Germany. And it’s set in a time when you didn’t exist. So, I mean, it’s all from your parents’ experiences or what they said. How did you go about that? What kind of research went into telling this story?

There are other characters in the book as well. In some chapters, the narrator appears in first person; there’s a grandniece of my parents, a granddaughter of the grandmother in the book, and so on. I don’t research before I write a book. I’ve discovered that when you do that, you become overwhelmed by the wealth of information you’ve gathered. You don’t know how to proceed. I’m speaking for myself. I prefer to write the book and then figure out where I need more information. That way, you know what you need to know and how much to research.

“‘Writing is the one thing that pushes time back and gives you some control over time, vanquishes time, annihilates time, it destroys time, it stops time. For me the only thing that does that, is when I am immersed in a poem or a piece of fiction.’”

What is your relationship with poetry, and what is your relationship with fiction? How would you kind of address that?

I’ve never made much of a distinction between the two. Each project sets its tone and pace and voice. Even when it’s prose, you use the same tools that you bring to poetry. It’s just that the frame is different. Each form dictates its voice. And it is a question of trusting the voice and letting go. Earlier, when you were asking if it was thought out or organic? With me, it’s always organic. When I start, I have very little idea where I’m going or where I’ll end up. I’m not one of those people who have the plan of the book before they start, each chapter, and what happens in each chapter. I discovered that as I’m writing. And I find that a more interesting process. Although if I were to write, say, a crime novel, a detective story, I might work it out beforehand.

Has the process evolved?

It’s been the same. The only thing that has changed is that I’m faster now. If I were working on The Book of Chocolate Saints today, it wouldn’t take me six years. It would take three or four, because I’m more focused on the sense of how to proceed and not to let things wait. At this point, even if I’m travelling, if I have to go somewhere, I’ll work for a couple of hours, at least, in the course of the day, preferably first thing in the morning. With a book of poems, you work in bursts, you can forget about it for a month or two and come back to it. But a novel takes shape as you work on it, day after day. You have to be at it every day for the interesting stuff to happen, for the subconscious to throw up nuggets that delight you or surprise you. For me, those are the moments that make a book.

So, while writing The Elsewhereans, did you get surprised? Can you share a little anecdote or something?

After I thought I had finished the book, I sent the manuscript to Rahul Soni, my editor at Harper Collins. We had a back-and-forth that added to the narrative. In January, my mother died. I rewrote the end of the book because it is her story. It starts with her as a teenager in Kerala. I gave the book a new ending, which was all to do with her death, her ashes going back to the house by the river where she was born. And then, of course, I realised that the book begins and ends with a river, it took a full circle. I ended up dedicating the book to her.

What an evocative turn of events. So, where did the name The Elsewhereans come from and as it’s genre-bending, where will it be placed in bookshelves, and what category of genre would you give it?

I’ve thought about this a lot, because where are you going to place it in a bookshop, right? I’m calling it ‘a documentary novel’. The title occurs in the novel. There’s a reference to my mother, when she’s living in Hong Kong, she realises that she no longer belongs to Kerala, she now belongs elsewhere, she’s become an ‘elsewherean’.

What next?

I’m working on a crime novel, and this is the first time I have written a chapter-wise breakdown. The genre I read second to poetry is crime fiction. I’ve always been a devotee. I look at it as comfort food, it has helped me through the darkest moments. If you have read a couple of thousand crime novels, which I have, you are bound to want to try your hand. I had various scenarios in my head about how this story would proceed. It took a while to settle on the two characters that propel the narrative. I’m not going to get into details, but I’ll say it’s a mother-son story. And it’s probably the first book I have written with no ghosts in it. I’m setting myself the Georges Simenon challenge. Simenon wrote about four hundred novels. He created a detective, Maigret. Wonderful slim books, around two hundred pages or so, full of odd wisdom. He lived in Paris, but he would check into a hotel in the city, I’m sure a good hotel, and he’d live there for six weeks. When he checked out, he left with a manuscript. That’s my plan. I’ve been thinking of Kathmandu, where I don’t know anybody.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra

21.06.2025