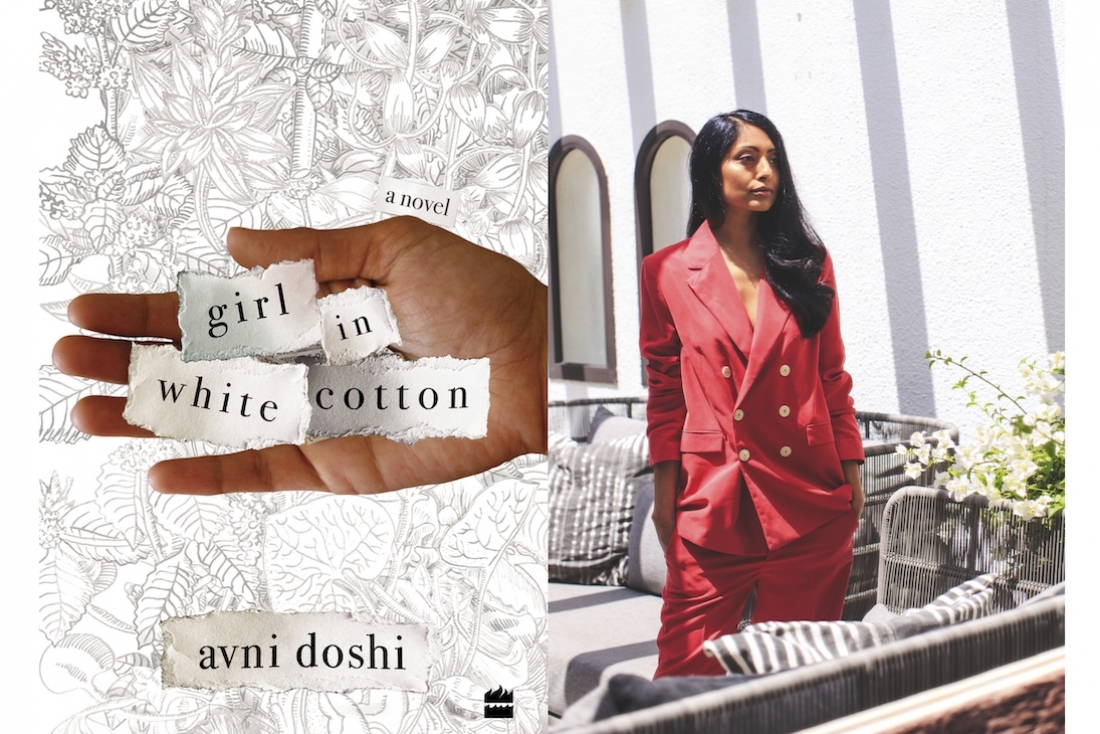

Avni Doshi had some beginner’s luck as a fiction writer. She had just started writing Girl in White Cotton when she heard about the Tibor Jones prize in 2013. She decided to use the prize as a deadline to finish the first draft, but in the end she won.

‘Soon I had an agent – I applied to and was awarded a fellowship. Everything was flowing and felt effortless until the time came to revisit the manuscript. I now really believe there is a danger in showing your work too early. It wasn’t ready. I wasn’t ready. I didn’t know how to rework it, but I kept trying, and that’s all you could see in those drafts. Effort. Pretense. I was trying to write what I thought I should write. I was trying to sound a certain way. It took me seven years and eight drafts to find this character’s voice.’

Here’s all that transpired in that time, bringing to us one of the most poignant debuts of the year.

When did writing begin to shape your identity?

I’ve always had a tendency for daydreaming, fantasizing, replaying scenes in my head and then changing them, inserting myself into them. I suppose I privately knew I was a writer in the eighth grade when I wrote a series of bad poems in iambic pentameter and my kind English teacher Ms. Kardos began calling me “the poet”. I heard that and thought, well of course, that makes sense. (I haven’t written a poem since then, by the way.) I don’t think I called myself a writer aloud until I was in my twenties, and then the word writer was always preceded by the word art - I was an art writer for many years. Fiction was more of a secret, more about pleasure - something I did to get away from the academic and critical stuff.

With writing, there is always so much doubt, and so the ways I identify with being a writer are always in question, always a little unclear. I usually think I don’t know what I’m doing, that I’m not qualified to put my thoughts on paper. No matter how many people say that they think what I’ve done is fine, or even good, I have a lurking sensation that I might just be an imposter. Validation from the world doesn’t sink in easily. Maybe because writing is so solitary, so lonely - and the process for each writer is so distinct - we create our own stories about how we make stories, and whether they’re worthy. We see the mess, the bad sentences, the countless drafts - the whole archive of failure. No one else sees that. So I can never really fully believe what other people tell me about my writing. They mostly see the polished, hard-bound product. What about the rest? What about the truth?

And so I am not even sure whether my identity is that of a writer. I suppose it is there in the way I approach the world - often as an observer. On the outside of things. Is identity grounded in the quotidian, in how you spend your days? In that case I was a writer - but lately I’m more of a reader, an editor and a mother.

Take me back to the moment in which the Girl in White Cotton was conceived.

Girl in White Cotton was conceived in Pune, in my grandmother’s 8th floor apartment. There is also a small balcony at the back where we hang all the laundry and wet towels to dry. The glass partition on the balcony was discolored and looking through it changed the view. I imagined a mother peering over the glass and her young daughter stuck below, seeing something entirely different from the ground. The first scene I wrote was set in a house with a balcony like this one, partly encased in glass, with a mother and daughter talking, unable to reconcile their opposing viewpoints, each one ignorant of what the other had seen. And there was another image of a woman looking in a mirror, partly in shadow and the two halves of her face seem to belong to two different women.

The scene read very surreal - almost dreamlike and a bit confusing. In fact, it was the first thing many early readers suggested I cut, which was entirely appropriate. That scene had an energy but the language didn’t feel like mine - probably something from my unconscious that came out, that I don’t have contact with. It was interesting but didn’t need to go into the final draft. I think of it as a preparatory sketch.

I should mention that when I’ve gone back to my grandmother’s house since then, and have tried to look for that same effect in the glass, I’ve found it doesn’t actually exist.

How did you find Tara and Antara?

Antara, the daughter, was really conceived as her mother Tara’s foil but through the process of writing and discovering the characters, they both evolved into something more complex. I found that they kept remaking each other as I wrote - and that is where the tension in the relationship comes from. It’s a kind of polarity and obsession you normally discuss in terms of erotic relationships. If this were the story of a father and daughter, you might even describe it as Oedipal. In a way, I was rethinking or reframing the Oedipus complex.

The story presents the argument that memory, truth and identity are never absolute, ever shifting. Is it unfair, then, to degrade human life to objectivity?

I think rather than an argument it’s another central tension in the book. Biologically and culturally we crave categories. We think they keep us safe, but what are the dangers of stripping away nuance?

It’s easier to keep things black and white, distant, objective, but what are we hiding from ourselves by taking that stance? On the other hand, sometimes Antara is too open, too empathic, and she crosses that line into pain and dissolution. I’ve definitely experienced that myself, when I’m writing. It’s magical but also a little scary. I forget where the character and the story ends. And I think that is what I’m really interested in - how everything begins to dissolve at the margins.

Whose lines would you steal if you could?

Do you mean another writer? Rachel Cusk. Deborah Levy. Don DeLillo. Javier Marías. James Salter. I’ve recently started reading more short stories, and Grace Paley is so sharp. Sheila Heti’s Motherhood is a book I wish I’d written.

Where do you write your best?

I think the place is less of an issue than the time. I can write with my laptop on any bed. I used to have a really lovely study but my baby sleeps there now. Actually I think the bed is the best because there’s something sleepy and still about my bedroom and I can write from a dream state. Early in the morning when I’m just barely awake is a good time. That doesn’t happen much anymore with my son. But I feel I’ve always fetishized the right time and circumstances in which to write, and now it’s time to put that aside and get on with it.

What is your biggest obsession that results in inspiration?

I tend to get obsessed with researching different topics. Alzheimer’s was a big one, especially after my grandmother got sick. There was a time when all I did was look at and think about art, or even design. My house became an obsession when I moved in. I would spend months thinking about fabrics and textures and wallpaper.

Travel used to be a big one for me. There was a time when I lived out of suitcases for years at a time. (I have Jupiter at 0 degrees Sagittarius.) But now I don’t travel very much. My life is very routine, quite domestic. However I’m becoming more and more neurotic, so maybe I should start traveling again.

But reading is a good way to travel when travelling isn’t possible.

What has been that one most difficult and naked thing to put in words?

I can’t identify one thing. Trying to make contact and write about my shadow side is hard - the parts of myself that I don’t want to acknowledge or look at. The mother-daughter relationship was hard to write without trying to be polite or gentle. I think I was brought up to not say certain things in public, and with my book, I’ve had to undo that learning. But the parts that were the hardest to write feel the best to get right, so it’s always worth it.

What is the responsibility of the writer, or the collective purpose of writing?

I don’t like to speak about collective purpose because writing is varied and particular. I write alone and the only responsibility I place on myself is to attempt to write what is true. I don’t mean factually true - I write fiction after all. I’m also not interested in universality. I suppose I hope to achieve something like authenticity (although I think that word is really overused).

What book would you send to the leader of a government that imprisons writers?

I would probably not bother because I can’t imagine the leader who imprisons writers would open a book I would send him. But I’m reminded of a compelling large-scale installation by the artist Shilpa Gupta. It’s called 100 Jailed Poets. She overlays voices reading the work of jailed writers and the written texts are skewered by metal spikes. I would probably organize for this leader to experience Gupta’s installation. The effect is visceral. The voices will not be ignored or silenced.

Have you started working on other writings yet?

I still feel I have Antara’s voice in my head so it is difficult to start a new novel. In the meantime, I’m reading a lot, and scribbling in the margins of other peoples’ books.

Text Soumya Mukerji