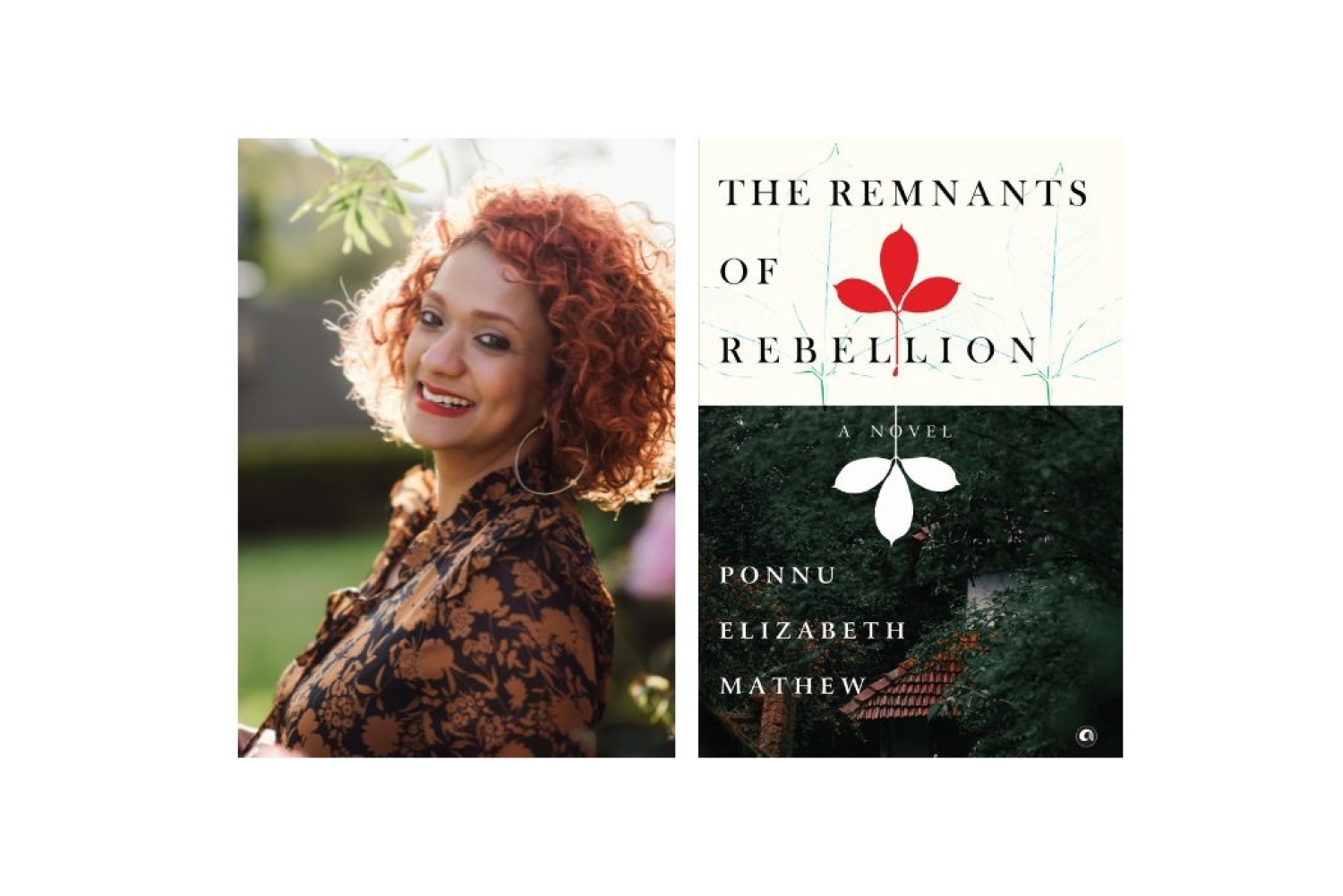

Shannon Da Rocha, Rocket Photography

Shannon Da Rocha, Rocket Photography

The Remnants of Rebellion is a novel that spans across three generations. Aleyamma, the protagonist of the novel, arrives at a haunting bungalow she inherited from her great grandfather, set within the rubber plantations of Kerala. We follow her as she finds herself entangled in a legacy that she did not quite expect, and knew very little about. The novel slips between the past and the present; between Eesho’s arrival as a plantation supervisor during a time of political unrest, and Aleyamma’s search for answers amid buried histories. We’re in conversation with Ponnu Elizabeth Mathew about writing memory, ghosts, and rebellion.

Personal and the Political

The Remnants of Rebellion is, at its core, about the many forms rebellion can take—political, personal, and social. While the backdrop is shaped by the larger upheavals in the country, I always kept the focus on the story itself, particularly on Aleyamma, her grandfather Eesho, and the people who matter to them.

For me, the writing process was deeply immersive. These characters have lived with me for over fifteen years, and the act of writing—over more than five years—often felt like I was inhabiting their lives. Their struggles, choices, and moments of rebellion became my own as I wrote. I did not consciously separate the personal from the political; the two were always intertwined in the characters’ experiences. My job was to be true to their journeys and simply write down what unfolded.

In the end, it was always the story and the characters that guided me, allowing the personal and political strands to naturally weave together.

The Setting

The setting of The Remnants of Rebellion is a Syrian Christian household in Kerala. The novel unfolds across two timelines: the 1960s, following Eesho’s story, and the present day, through the eyes of his granddaughter, Aleyamma.

But I take a much broader sweep of the canvas. The narrative goes back to the legendary arrival of St. Thomas the Apostle in Kerala in 52 AD, the birth and evolution of the Syrian Christian community, and the waves of change brought by the Portuguese, British colonization, caste dynamics within the tradition, and later, the Naxalite movement and current politics in the state. These layers of history shape the family’s world. The novel is as much about these intertwined histories as it is about the intimate lives of its characters.

The Creation

To faithfully portray this period of Kerala’s history, I read and asked questions. My background in journalism helped me that way. I read widely on the themes central to my novel, but two books were especially influential: Kerala's Naxalbari: Ajitha, Memoirs of a Young Revolutionary, which offers a firsthand account of the Naxalite movement and its impact on Kerala’s social and political landscape, and Modernity of Slavery by P. Sanal Mohan, which provides deep insight into the complexities of caste and social structures.

Beyond books, I sought out personal stories. I spoke with people who had participated in or witnessed the Naxal movement, gaining invaluable perspectives that went beyond what was available in print. Since the novel is set on a rubber estate, I also engaged with people who manage and work on rubber plantations to understand their lives and the socio-economic realities of the time.

Challenges

At first, I assumed that portraying a time I hadn’t personally experienced, like the early and mid-1900s, would be the most difficult part. But to my surprise, those sections flowed quite naturally. Perhaps stepping into a more distant past gave me the freedom to imagine without being weighed down by the complexities of the present-day world I know so well.

In contrast, I actually found writing about contemporary times more challenging. Capturing the nuances, contradictions, and rapid changes of today’s world required a different kind of sensitivity and honesty. I sometimes feel more at home in the rhythms and obscurities of the past than in the noise of the present, much like Aleyamma.

Writing Process

I truly don’t think I could have written this book, at least not in the way it exists now, without my own cultural background. I’m writing from within the community, about the community I grew up in. So much of what shapes the novel comes directly from my lived experience: the people I observed as a child, the rhythms of daily life, the food we shared, and the rituals and mysteries of church liturgy that both fascinated and confounded me. My cultural heritage gave me the language to bring the characters to life with authenticity, wit, and nuance.

Literary Inspirations

Whenever I hit a writer’s block while working on this book, I would reach for my well-worn copy of The Moor’s Last Sigh by Salman Rushdie. I’d simply open it at random and start reading. There’s something about Rushdie’s language that always jolted me out of stagnation. His craft was not only an inspiration, but also a practical tool for me; reading his work reminded me of the possibilities of the novel form and helped me find my way back into my own story.

The Future

I’m currently working on two new books—one fiction and one non-fiction. The first is a collection of short stories set in Kerala, unified by a central theme: in these stories, everyday implements of nourishment and ritual—the cherava (coconut scraper), the aaduvaal (butcher’s knife), the pressure cooker, and sacred objects like the church paten and chalice—become powerful metaphors for the centuries of injustice faced by women and the marginalized. In these stories, the women fight back. They reclaim what was once used to bind them, turning everyday objects into emblems of rebellion, survival, and power.

Alongside this, I’m also researching a non-fiction book that traces the history of the Syrian Christian community in Kerala. This project is still in its early stages, but I’m delving into archival materials and oral histories to uncover the layered past of the community.

Both projects allow me to continue exploring the intersection of personal stories, cultural memory, and historical change.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

18-07-2025