Photography: Chandni Gajria

Photography: Chandni Gajria

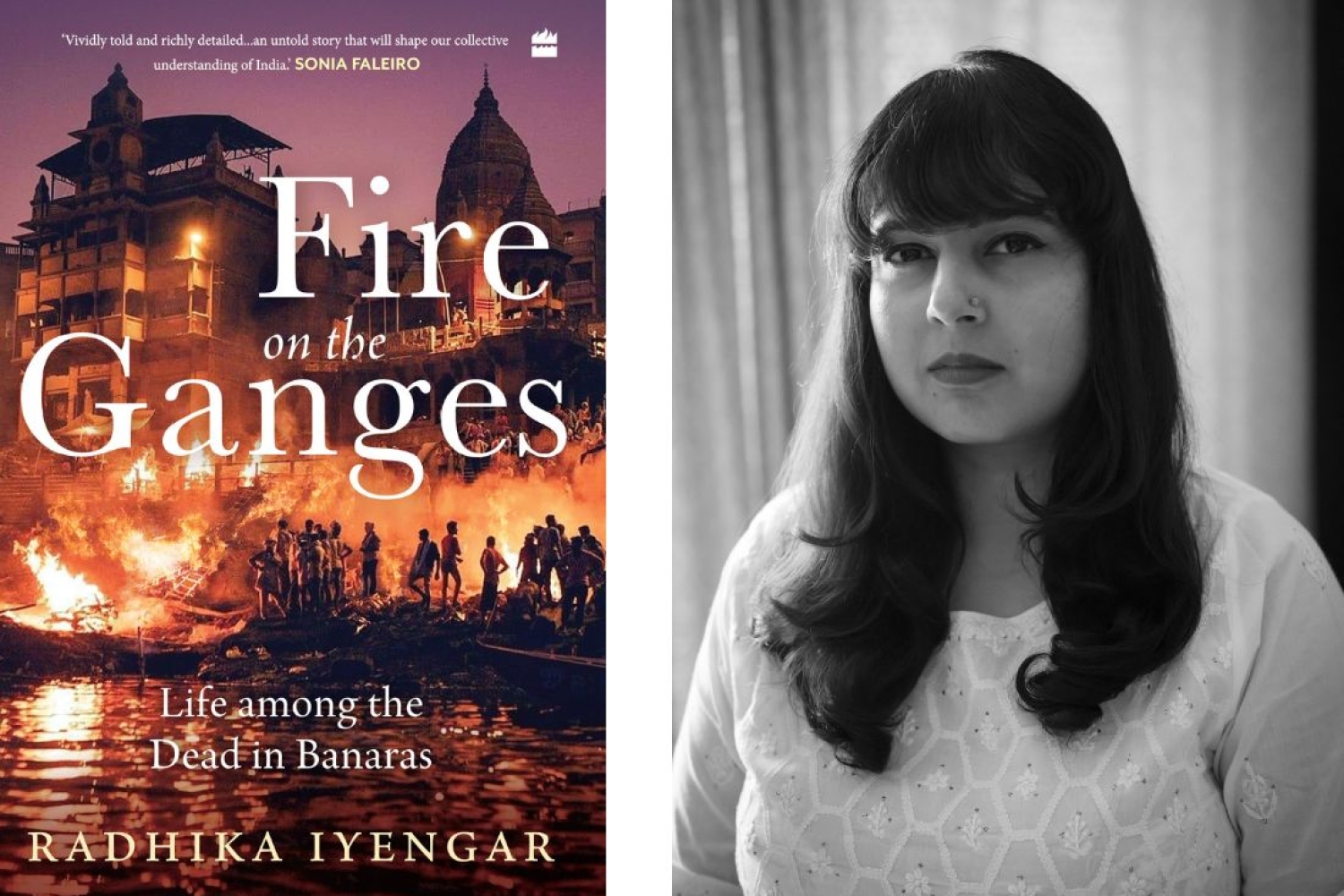

Fire on the Ganges: Life Among the Dead in Banaras (HarperCollins India) is a path-breaking work of non-fiction on the strength, struggles and ambitions of the Doms, a Dalit sub-caste traditionally responsible for cremation rites, bound by age-old traditions. It is believed that Hindus cannot achieve moksha (liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth) without being cremated by a Dom. Despite their supposedly traditional auspiciousness, they are not spared from the daily acts of caste prejudice. This book focuses on the journey of select individuals from the Dom community who have managed to break free from the vicious cycle of casteism that has long defined their lives.

Radhika Iyengar’s work in the realm of slow journalism is the result of countless hours of interviews conducted over approximately eight years, conducted during field visits to Manikarnika Ghat and the Dom neighbourhood and via video calls, in the pandemic. Her motive was to truly understand the experiences of the Doms beyond mainstream coverage, accomplished through documenting the stories of individuals who aspired to lead lives on their own terms, unburdened by the shackles of caste. Iyengar, Platform’s Deputy Editor, shares with us her experiences of reporting at the cremation ground, engaging with the Doms, and the profound impact this had on her.

Why did you choose to write about the Dom community?

I had read an article about the Dom community, which led to the initial interest. When I tried to learn more about them, however, there wasn’t enough information available. Whatever little was available, had a narrow, singular narrative associated with the Doms, which is that the men labour at the ghats and perform crematory work.

I wanted to understand the experiences of the Dom men beyond that lens. I wanted to know about the women who remained largely unseen in public spaces; about the children in the community and whether they had dreams of a future that was not pinned to a life at the cremation ground. If they did, what were those dreams and what opportunities did they have to pursue them? At the time, however, I didn’t realise that I would end up investing many years of reporting on the community, which would eventually turn into a book.

Tell us about your research and your process of interviewing.

Between late 2015 and early 2023, I held several hours of interviews. Photographs took the form of visual note-making. There were also handwritten notes. I read books, watched films and documentaries, and referred to countless news reports. Over the years, the methodology of interviewing evolved too. Initially, the interviews were formal but as the community members became more comfortable with my presence, the interviews organically took on a more open and conversational form. It was during these lengthy conversations that significant insights emerged. While reporting, I’ve realised that one must learn to make patience a friend, ask informed questions, listen with empathy and attention and become a keen observer of the surroundings. The smallest gesture of an individual’s response to their environment, for instance, can reveal something significant about their personality.

What were some of the challenges you faced in doing a work of slow journalism?

At Manikarnika Ghat, everywhere you turn, there is an overwhelming presence of men. There are wood-sellers, corpse burners, shop-keepers selling funerary paraphernalia, barbers with portable shaving kits, local guides, boatmen and so on. I had to come to terms with that in order to report at the cremation ground. Initially, the corpse burners were not very forthcoming. I don’t think there are many people who enjoy discussing their lives with complete strangers. In that sense, the Dom men weren’t entirely receptive to an outsider approaching or talking to them either – particularly a woman. Gaining their trust then (although challenging) was of utmost importance. The corpse burners were extremely time-conscious as well. Understandably, they did not entertain anyone while they were on their shifts, therefore, I had to wait and speak to them when they had the time to do so.

On one of my initial visits to Manikarnika Ghat, I made the mistake of standing too close to a cluster of lit pyres. The air was thick with smoke. For the uninitiated like me, within minutes, my head began to throb and lungs felt heavy, I almost fainted. I realised then how excruciating it was for them to work in such conditions. To stand for hours – particularly in peak summer, amidst burning pyres that radiate immense heat, without any protective paraphernalia, with flakes of ash and smoke irritating your vision – amounts to working in an unstable and unpredictable environment. I decided then that I had to follow through and recreate that sense of urgency for the readers who hadn’t been to Manikarnika Ghat and give them a modicum of what it might feel like to be working at the cremation ground.

Did writing this book and reporting on the community also bring a change in you somehow?

Before I began reporting on the Doms in Banaras, although I was cognisant of the prevalence of caste-based discrimination in our country, I didn’t understand how deeply rooted it was or of the varying degrees of caste trauma that existed. For instance, during one of my field visits to Chand Ghat, I was informed about a par- ticular shop owner from the dominant caste who would ask his Dom customers to leave the money at the counter and stand at a distance after they purchased an item from him. If change needed to be returned, he asked them to cup their hands so that he could drop the coins into their palms. We read about grisly acts of violence like flogging and honour killings in the newspapers but there are perpetuating smaller acts of violence that occur every day, which have deep, long-lasting psychological impact on those who experience it. So, the change was inextricably linked to my learnings as a journalist and as a human being. My reporting experiences certainly made me more aware, informed and empathetic.

This is an all exclusive excerpt from our Bookazine. To read the entire article, grab your copy here.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 25.11.2023