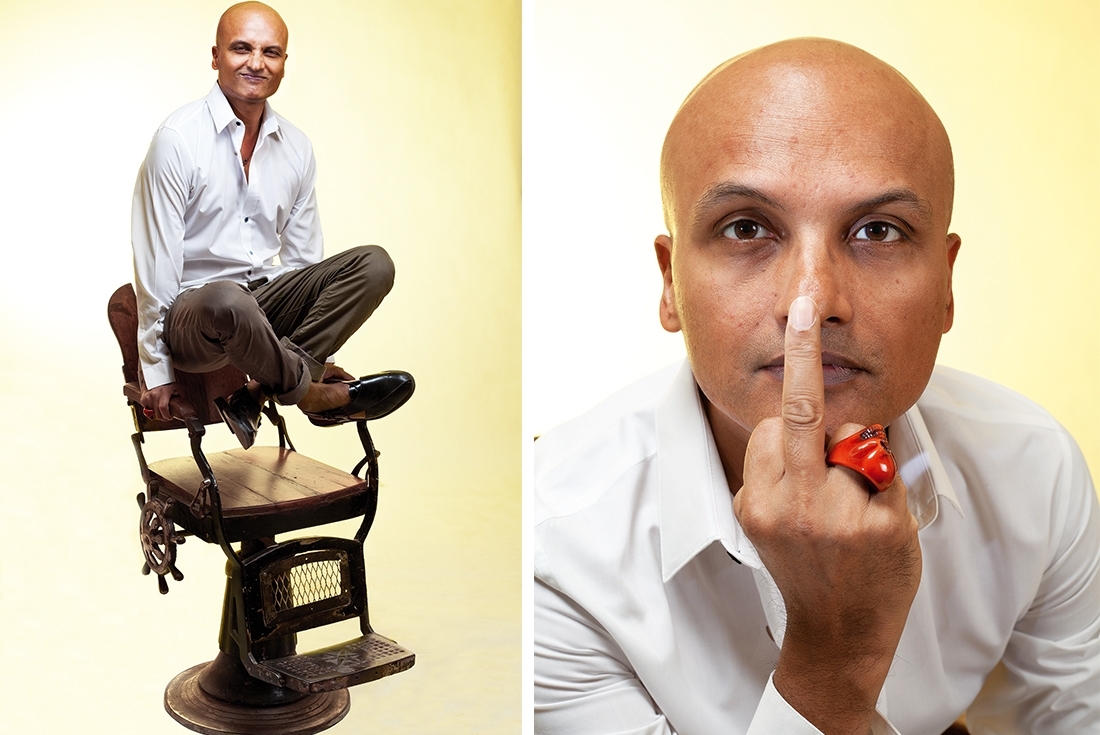

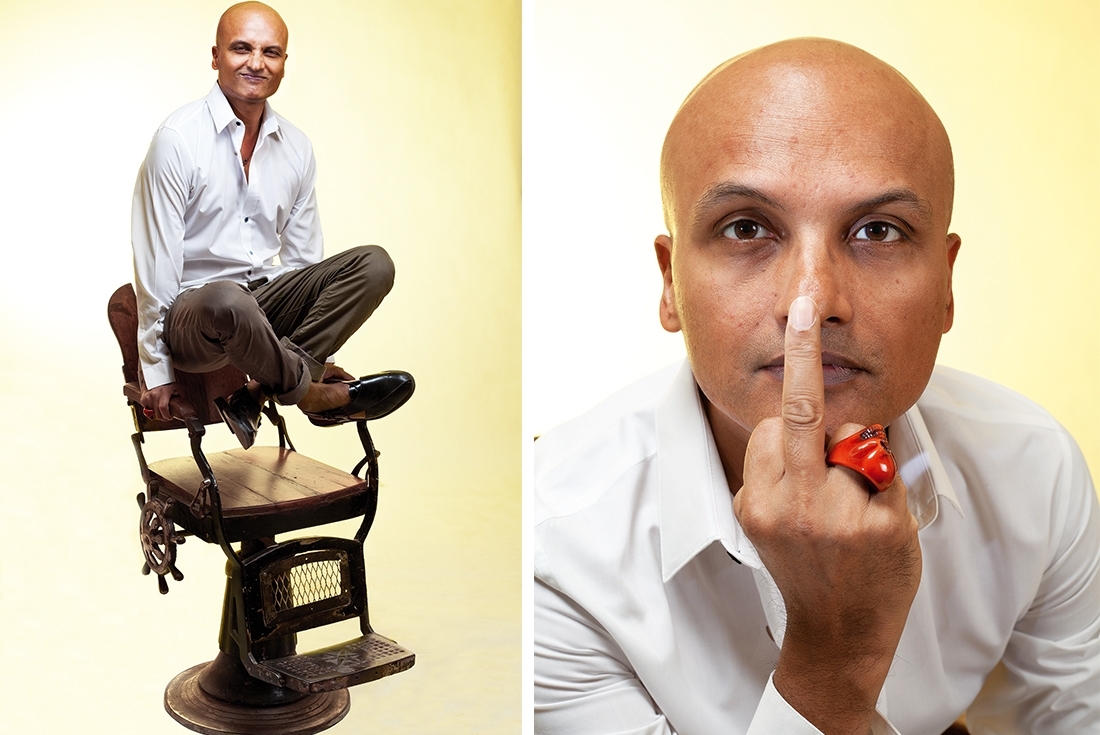

Photography by Raoul Amaar Abbas

Photography by Raoul Amaar Abbas

We revisit our interview with Jeet Thayil who has recently released his new book, Low, and will be seen as a speaker at this year's Jaipur Literature Festival.

A Man Who Once Held a Pipe

A large headed boy, born with the help of a midwife, makes his first appearance in the world on October 13th, 1959. Born to Syrian Christian parents in Kerala, little did the enfant terrible know what path he could take, what life threatening experiments he would perform, how he would react to and what he would take away from the sixties and seventees, who he would cross paths with, what substances he would consume or how he would end up becoming the master storyteller – Jeet Thayil.

I was first introduced to Jeet when I read his very unconventional debut novel that houses a motley crew of compelling characters in a world that no longer exists. Instantly, the book, and his life that resonates in every page of the award winning Narcopolis, enthralled me. To the conservative mind he could be passed off as a junkie, but to the worldly mind he is an inspiration in every way. In two years he made up for the twenty years of his intoxicated life and turned it around. Those years of getting high and frequenting the opium dens turned out to be an apprenticeship, a kind of journalistic emergence that would eventually turn up in a book, of that he had no clue. The need to want to make some record of a world that no longer exists, motivated Jeet to capture the world that he once belonged to through the pages of his fearless and arresting first book that garnered tremendous acclaim, raised eyebrows and has become a regular at every award function.

A performance poet, a line drawing artist and a prolific writer, Jeet has always expressed his creativity through various mediums. As I got comfortable in his old-school Calcutta chair, he began unraveling the various stages of his life that led him to Narcopolis.

CHAPTER I

The Large Headed Intelligent Negativist

Where were you born?

I was born in Kerala but I’ve never lived there. My parents were in Bombay at the time. I was born with the help, or hindrance, depending on which way you look at it, of a midwife. My parents were educated, intelligent and fairly modern, but they chose to follow an inexplicably foolish and obsolete tradition, that the wife must return to her maiden home to have a baby. The problem was, my mother’s ancestral house was in a remote part of Kerala, inaccessible by road. Pregnant, she walked across paddy fields and some pretty dangerous terrain to get to the house. It was a very difficult birth, it took a day and a half, and my mother almost died, my head was too large. Under normal circumstances, the doctor would have insisted on a cesarean, but we were in the hands of a midwife in a remote location. Afterwards, my grandmother said there would be no more births in the house. Mine was the last.

So you grew up in Bombay?

My father was a journalist, which he still is. He worked with The Free Press Journal in Bombay, and for a while he was the editor of a newspaper in Bihar, The Searchlight. We lived in Patna for some years, and Bombay, and when I was eight my family moved to Hong Kong, where my father became an editor with the Far Eastern Economic Review.

What entertained you in your teens?

Drugs. I started experimenting around the age of fourteen. I also started to play the guitar, to write poems and make drawings, all around the same age. It was the seventies, an amazing time. When people say the sixties, they mean the seventies, because in most parts of the world the sixties occurred in the seventies. The music, the writing, the art and fashion, political and spiritual consciousness, sexuality, individualism, everything sort of exploded. I felt it at the age of thirteen, as a time of enormous possibility, really, a time for the breaking or questioning of every rule you thought had been set by your parents’ generation. I was rebelling, and, in retrospect, I was rebelling without a cause, which was something I realized much later. In my defense, I was thirteen, and like most thirteen-year-olds, I was a complete idiot. It all seemed very positive at the time, but it wasn’t. It was exactly what happened to the sixties: we thought the movement was about love and peace and flowers, but it was also about something demonic. Woodstock became Altamont. Love, peace and revolution turned into addiction, black magic and murder. The good drugs, the weed and LSD, which opened your mind and expanded your consciousness, they morphed into the killer drugs - into heroin and speed. And all of this happened in the space of a couple of years.

Were you intelligent?

I read all the time, but I found tremendous excitement in negativity. I was an intelligent negativist.

CHAPTER II

A Hard Working Junkie

Opium dens, college, getting high and yet you were hard working - how did that work?

I returned to Bombay from Hong Kong when I was about eighteen, and I discovered opium. Before moving to India I was never addicted and drugs were never a problem. But I had been suspended from school - I got into trouble with the police, I was obviously going the wrong way, and my parents sent me to India thinking it would tame me. They sent me to Wilson College, which, it just so happened, was very close to Shuklaji Street, the heart of Bombay’s old opium world. I didn’t know then that in a matter of four years this world would disappear, vanish into the unreliable pages of history. For me, discovering opium was like discovering a literary continent that had until then only existed in books. The fact that it felt good too was a kind of bonus to the adventure. I would go to the opium dens in the morning and turn up in the afternoon for classes, often nodding off, though I didn’t do too badly. After the BA was done, I started working. I joined a newspaper in Bangalore as sub-editor. I held that job for a year and half. For the next twenty years, I had every shitty journalism job you can imagine, and some you can’t. They were often awfully paid and I had to work for egomaniacs and lunatics. Some jobs I held for a year, some for two or three years. I was often depressed. I hated my life. I wanted to be a writer. I also had good journalism jobs that paid well. For a while, I was the Bombay correspondent for publications in Hong Kong. I earned about a lakh a month, which, at the time, was way too much money. The point was I did these jobs for cash. I was never that junkie that sold things from home or stole from friends. I supported my habit by working. I think, it’s thanks to a protestant work ethic, or a Keralite Christian work ethic that was stronger than the compulsions of the drug.

CHAPTER III

The Clean Up Act

What was that point of realization that made you change your trajectory?

I had a health crisis in New York in 2002 - I was diagnosed with a chronic liver problem. I knew if I didn’t clean up I was going to die, and for the first time I felt my mortality, I saw the shape and length of it. During the years I was doing drugs I was convinced I would live forever, I believed I was indestructible, immune, nothing would happen to me. So when it did happen, I was shocked. I pretty much quit overnight. I started living healthy, started working out and eating well, and I quit drinking, turned vegetarian for some years, quit cigarettes. In the past I had joined many rehab programs and cures, around two dozen, without much success. This was the first time it worked. I joined a methadone clinic in New York for a year and a half. Methadone programs in the United States aren’t designed to help you quit drugs, but to keep you off the street and stop committing crimes. You have to undergo urine tests a few times a week and if they find drugs in the test, they up your methadone dose. The theory is that you are not doing enough methadone, which is why you are still using heroin. I reduced my dosage every week, over a year and half, until I was free of it. I was told later I was the only person who had done it in their program. I think the reason I could never go back to heroin is because that year and a half was so difficult, so long drawn out. In a way it’s good that it was painful.

CHAPTER IV

The Face Behind the Mask

It took great courage to write a story that is so close to your own reality - what made you put yourself out there without any hesitation or apprehension?

It’s a novel, so you know it’s a mask. When I returned to India in 2004, I was planning to write a book of non-fiction about Indian religions. I don’t know what I was thinking. I traveled around India and I was going to write about churches and temples and then I got this residency with the Bellagio Foundation at Lake Como. I was working on this non-fiction book and one day I wrote a chapter that is in the middle of Narcopolis, ‘A Walk on Shuklaji Street,’ and as I wrote it, all this stuff came tumbling out. It was like tapping a vein. I couldn’t stop. At the same time, I felt beholden, because this was a world that was gone and most of its people were dead, they’d never get a chance to speak, and I felt it was a way to chronicle lives and a time that had disappeared. I put everything I had into remembering and I was amazed at the kind of journalistic detail I had stored away without even being aware of it.

That was another thing I discovered as I was writing the book, that if you spend a long time on one story, on one book, you discover things about the story you are writing that you could never have known when you started. This kind of realization happens when you live with a story for years: you discover alluvial layers, you excavate, and then you bring it out into the sunlight. For me, that was probably the most exciting thing that happened during the writing of the book. And I discovered that I didn’t like who I was and that’s apparent; the ‘I’ character, the so-called narrator is the least interesting, the most feckless, watery kind of guy. His name is Dom Ullis and if you’re drunk and slurring, Ullis may be mispronounced as Ulysses. The difference is that Ulysses wandered, whereas Ullis drifts, any which way. He is the character with the least amount of ballast. He will go with the breeze wherever it blows, and I think it reveals a dislike on the part of the author for the character that is closest in terms of biography.

What is the difference between the Bombay you wrote about and the Mumbai that it’s become?

As far as the city goes, I was living in Bombay for the last year and a half when I was working on Narcopolis. The apartment that my family owned in Bandra had been sold when I was in New York, because I told them I wasn’t coming back. So they invested in a place in Bangalore, which they rented and I lived off that rent, a small but steady income, while I was writing Narcopolis. I realized that the Bombay I was writing about had no resemblance to the Bombay I was living in. Bombay in the seventies and eighties was a different kind of place. It was full of promise, a magnet, and the promise it made was that if you had ambition, talent, beauty, if you were willing to work hard, the city would reward you; if you brought money with you, it would be doubled. It assured you of a reward whoever you were and wherever you came from, whatever caste or community you belonged to. That was the promise and that promise has been broken, is broken every day, thanks to the city’s current management, the same management that changed its name from Bombay to Mumbai, that has divided people along religious lines, that has made people realize that they have to be aware of the religion of the person they are conversing with. These things would never have happened in Old Bombay. It is a huge disappointment.

CHAPTER V

The Writer of Now

How has life changed after Narcopolis?

Well, I never expected all this to happen. I thought I was writing a serious literary novel that would be talked about in five or ten years and would find its place in a generation down the line. I didn’t think it was the kind of book that would make immediate waves. It was the shortlisting for the Man Booker that did it. It changed everything. That nomination, and winning the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, made the writing of the next book less lonely. I knew I’d find a publisher; with Narcopolis I didn’t know if it would be published at all.

Sometimes a book has to gain acceptance and appreciation outside the country in order to get applauded here? Why do you think this happens?

I think we are the last colonials in the world. I don’t think the Chinese are. I was in Shanghai recently and was struck by how much weight they give to their own opinions about their own art and artists, which is as it should be. They don’t wait for approval from elsewhere, unlike us. We are liberal yet conservative, and we do not value our own history and art, not until they’ve been endorsed elsewhere, preferably in the west.

What is it about Newton Pinter Xavier that fascinated you enough to make him the protagonist of your next novel, Sex Lives of the Saints?

The first draft of Narcopolis was six hundred pages and I chopped it down by half. The first version had a lot of Newton. In the final version, he was in only one chapter - a chapter that occurs very early and kind of sets up the novel, and then he disappears. But that chapter collapses a decade of Bombay into a kind of set piece, and people who were there in the eighties will recognize a lot of it. Like Narcopolis, the new book has elements of the bizarre and fantastical, but it rests on bedrock. The Newton character is based on Dom Moraes and F.N. Souza, more Souza than Dom. They were contemporaries and they were similar in some ways. The thing is, Xavier is not a pleasant character: he cheats on everyone, on women, he is a thief who steals from himself, he is absolutely unreliable and selfish, but by the end of the new book, I hope he becomes likeable, a figure of vulnerability and passion, a heroic figure.

CHAPTER VI

Sex Lives of the Saints

PROLOGUE

The first time Goody Lol met God she didn’t notice his famous laugh or his obsession with his teeth. Feverish, she lay prone as the nights whitened and the moon rose red as blood in the gauzy skies above her. When she opened her eyes, she found a small man sitting at the foot of her bed. She was frightened by his smile. You? she said. You’re so dark. She thought his eyes were like images she had seen of the moon’s pitted surface, cool and palely waiting. At this, their first meeting, she told him of her crime and chief regret, that she had committed a sin against her family and all of humankind. The man asked: How old are you? Six and a half, she replied. Too young to sin, he said. Now talk about something else. What do you do?, she asked. He said, Nothing at all, but I work very hard at doing nothing. I work all day and most of the night and it isn’t enough. She said, How can you do nothing? It isn’t posible, not even for you. His eyes narrowed, as if he were seeing her for the first time, as if she were the one who had appeared out of nowhere. Then he nodded. Okay, he said, I make things. She told him that her friend, Sophie, drew pictures of armadillos, the best pictures she’d ever seen; and Sophie drew other animals too, animals that did not exist, but so detailed were the drawings, so exact, that it seemed they must exist, though perhaps in another country, or on an undiscovered planet. She’s always making things, said Goody. I want to make things too, like Sophie and you. It was at this moment that he seemed to lose interest in the conversation. He took a tiny mirror out of the watch pocket of his bellbottoms and held it to his face. He pulled his lips back, though he wasn’t smiling. Neither of them said anything. When he eventually spoke, his voice was flat and very soft. Go, he said, and make things, if that’s what you want, because you won’t live forever, nobody does. Goody’s eyes closed, and for a minute or two, no more, she dreamed of a field of flowers that swayed in the breeze, flowers she didn’t know the names of, flowers of many bewildering shapes and colors that stretched as far as the eye could see, and everywhere she looked, in the midst of the flowers whose names she did not know, were wooden crosses that grew like flowers; and when she opened her eyes, God was gone.

Our conversation with Jeet Thayil was first published in the Literature Issue of 2013. This article is part of the From the Archive series where we revisit relevant articles from our substantial article archive.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra