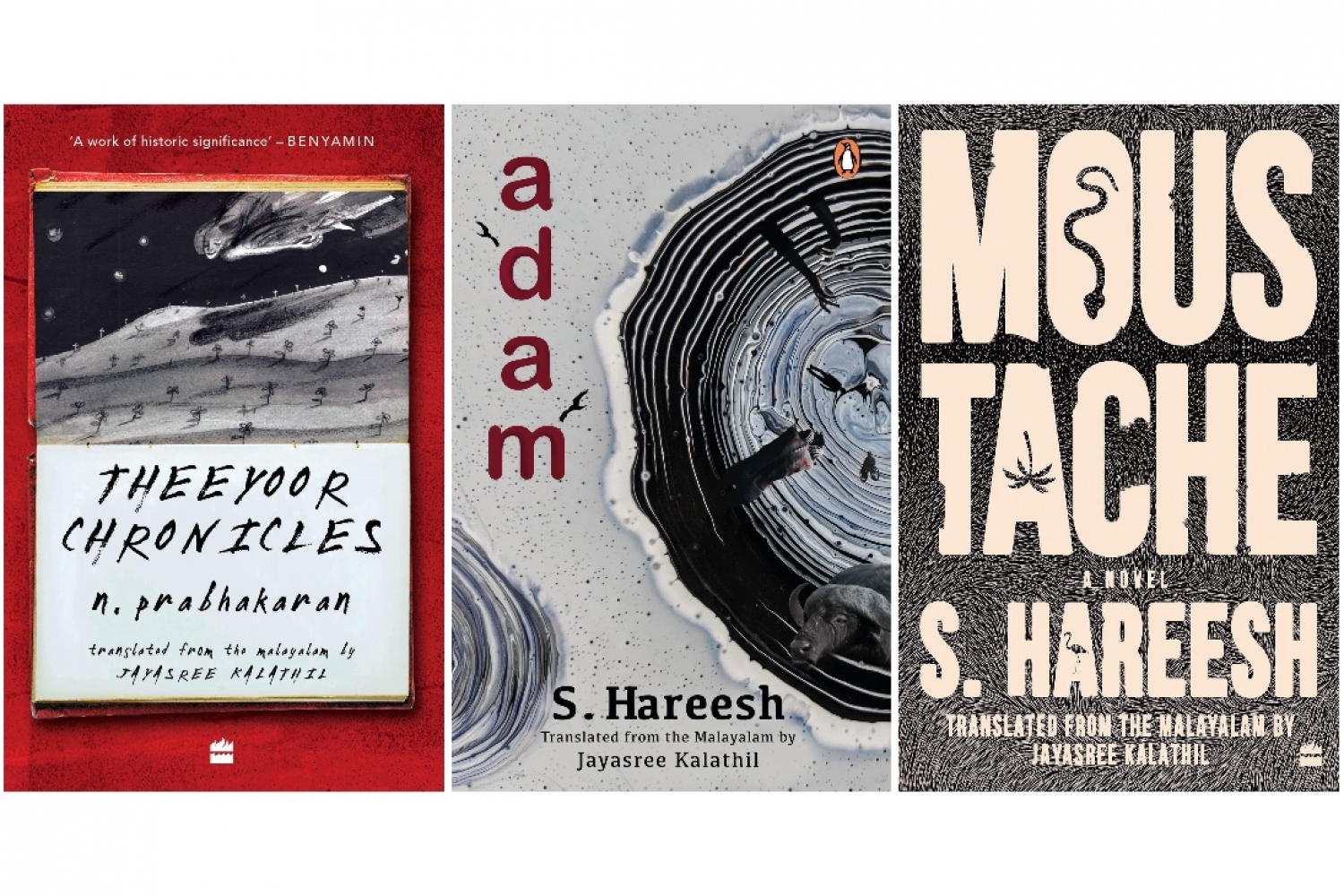

I was first acquainted with translator Jayasree Kalathil’s work when I read her English translation of S. Hareesh’s debut novel, Moustache, originally written in Malayalam. Immediately, I had a new author and translator at the top of my ‘must-read-more-work-from’ list. While I thoroughly enjoyed more of her translations, in the form of The Diary of a Malayali Madman and Theeyoor Chronicles, Malayalam writer N. Prabhakaran's extraordinary works, I was eager to delve again in S. Hareesh’s literary brilliance and her masterful translation of it. With Adam, a short story collection by S. Hareesh, now translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil, I was once again engulfed by their unique collaboration, one that will truly be remembered as essential and exceptional in the history on Indian literature.

I connected with Jayasree to converse about the art of translation. Excerpts follow:

Since last year, some of the greatest books I’ve read have been translated by you, from Moustache to Theeyoor Chronicles. How were you led towards the world of translation?

Thank you. That is such a kind and encouraging thing to say. I think what brought me to the world of translation is the love of storytelling. I have been an avid reader right from childhood, and literature in translation has always been part of it. I find the idea of stories traversing boundaries of language and culture fascinating. And the creative challenge of rendering someone else’s words and ideas into an entirely different language is equally fascinating.

With so many nuances and much that is said between the lines, how do you make sure a story is found and not lost in translation?

The idea of ‘lost’ or ‘found’ in translation — do we mean anything more by this than saying whether a translation has worked as a text? While the translator has a responsibility to keep as closely to the original text as possible, it is also a creative process, one that takes into cognizance the nuances of the language a work is translated into.

There is a whole debate in translation about foreignization and domestication, essentially whether or not a text should retain its cultural specificities in translation or whether it should be standardized to conform to the culture of the language into which it is being translated. Personally, I think this debate is a bit ridiculous, especially when it comes to English, a language of the colonizer which has several different cultural and linguistic histories across the world.

I think the biggest responsibility a translator has is to do all they can to be loyal to the story and to the author’s voice. However, I don’t think there is a singular, objective reading of a text. So, what ultimately gets translated is the translator’s reading of the text. We can do this without trying to obfuscate, by finding ways of being transparent in meaning and intention, and trusting the intelligence of the reader.

Can you take me through your creative process?

A translator, I believe, is the closest reader of a text. That’s where I start — as a reader interested and invested in the story. I read the text several times over before I begin, and I translate chapters or passages that I love the most first. It is only after I feel that I have a good sense of the author’s style, tonality and individual quirks that I begin working more systematically with the text. Telling the story in a different language is easier but translating an author’s unique voice is more difficult — S. Hareesh is a very different writer from N. Prabhakaran. I am very interested in how they use words, turn phrases and play with language, and I can sometimes spend hours getting a single word or sentence right. I am also interested in detail, and tend to go down rabbit holes reading about something in the story — for example, the irrigation system described in Moustache or mud therapy in Theeyoor Chronicles.

Adam marks your second translation of a work written by S. Hareesh. Could you tell me a little bit about how you approached this book differently from the one before, especially since Moustache was a novel and this is a collection of short stories?

As a reader, the short story is my favourite genre, so that definitely helped. A novel like Moustache gives the translator some room to be expansive in the translation, but a short story demands the preservation of the economy of words. I don’t know if Hareesh will agree with me, but, as a reader, I thought each story in Adam had a seed, a defining moment or idea, that was central to the story. Figuring that out was the crux, I think, and ensuring that it was reflected in the translation. In other words, one had to ‘get’ each story — and I do not mean that each reader will get it in exactly the same way — in order to translate it.

Photo by Adley Siddiqi

What is the greatest challenge of the art of translation?

Trying to convey something of the author’s unique voice. Translation is a collaborative process, and as the re-creation of a text, it will always reflect something of the translator’s style. Despite this, every translator has the responsibility to convey not just the story, but the unique way in which an author tells that story. I think that is the greatest challenge.

How have you been coping with the pandemic? Has it affected you as a translator in any way?

It has certainly brought to relief the privileges that we take for granted — from having a home to lockdown to access to vaccines. Like many people, it has also involved a certain amount of personal losses as well as a period of intense reflection. Writing — both my own work and translation — and reading have been my way of coping in this period.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

I am currently finishing work on a novel by Sheela Tomy. Another by Sandhya Mary and a children’s book are in the planning stages.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 10-01-2022