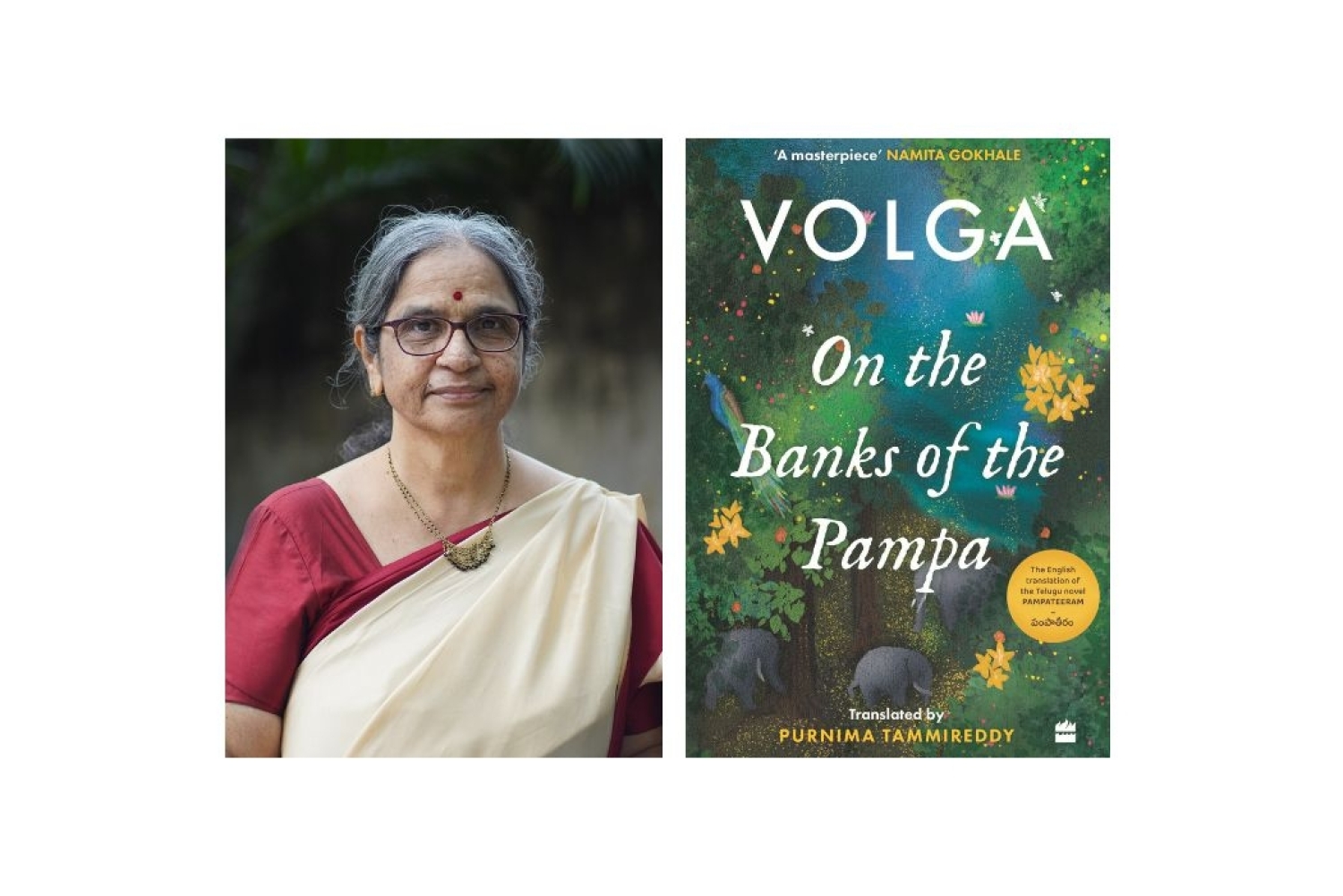

On the Banks of the Pampa is a quiet yet radical reimagining of Sabari’s story. It traverses devotion, displacement, and ecological resistance, all at once. In this powerful retelling of a moment from the Ramayana, author Volga and translator Purnima Tammireddy explore the emotional depth and political urgency of waiting, belonging, and bearing witness. We spoke to them about feminist storytelling, the challenges of translation, and the importance of listening to voices long left at the margins.

Where did your idea for this story come from? Why do you think this is an important story to tell?

This was not an idea that struck me like lightning—it was the result of years of quiet reflection. Sabari is a character from the Ramayana who is loved by many. I found myself returning to her again and again. Sabari is a forest dweller, yet she waits for Rama with such hope. Why? How did she come to know of him? Why was she so eager to meet him?

This novel engages with several of these pressing concerns. It raises questions that, I hope, will continue to resonate and spark dialogue long after the last page is read.

I don’t approach writing as a craft in the conventional sense. For me, it begins with feeling and thinking deeply—until I reach a point where the writing unfolds naturally. I always view society, both past and present, through a feminist lens. It’s not possible for me to tell a story without engaging with feminist politics. Clarity of thought and a deep emotional connection to the characters form the core of my process. I spend time understanding them, living with them.

“I don’t approach writing as a craft in the conventional sense. For me, it begins with feeling and thinking deeply—until I reach a point where the writing unfolds naturally. ”

Did writing this teach you anything new about resistance, liberation, or even yourself?

Every new piece of writing teaches me something in the process. This novel, in particular, taught me the value of persistence—and of holding on to hope, even in the face of uncertainty or failure. It reminded me that we must continue to speak what we believe, regardless of the outcome.

The contemporary Telugu literary landscape is vibrant and rich, with many voices telling stories rooted in their own identities and experiences. I hope these voices continue to grow stronger, inspire readers, and contribute to the creation of a more democratic literary culture—one where difference is embraced and diversity is truly respected.

What do you hope for readers to take away from this book?

I hope readers will begin to think differently about the idea of development—to question its real meaning and to recognise how, in its name, inequalities continue to deepen within our society. I also hope this story encourages readers to raise their voices in defence of diversity—both in nature and among human communities. Because protecting diversity is not only an ecological concern, but also a cultural and ethical responsibility.

Is there anything else you’re working on currently? What does the future look like?

I’ve recently begun working on a novel that explores the relationships between boys and girls, and how, in some cases, these are turning increasingly violent. The story looks at the various social, psychological, and cultural factors that influence young minds—sometimes pushing them towards aggression and, in extreme cases, criminal behaviour.

Translator: Purnima Tammireddy

What chose you to translate On the Banks of the Pampa and make it accessible to a larger audience?

On the Banks of the Pampa, like all great literature, carries many layers. But even in the original, it spoke to me deeply—as an ecological reimagining of myth. In an age shadowed by climate change, I felt a quiet urgency to translate it. The text unsettles our human-centred ways of knowing and understanding of our world, our idea and interpretation of dharma, and invites us instead to listen, to belong, to be one with the living world.

When did your journey with translation begin, and what set it into motion?

I began my journey as a translator in 2012, with Gulzar’s short stories into Telugu. Since then, I’ve translated Manto’s stories and essays, and Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar, also into Telugu. On the Banks of the Pampa is my first full-length translation into English. Along the way, I’ve also translated stories and poems of other literary giants—Harishankar Parsai, Fikr Taunsvi, and more.

Alongside being a translator, I also run an indie publishing house—Elami Publications—which focuses primarily on translations into Telugu. The translation landscape, especially Telugu literature making its way into English, has been evolving steadily over the past few years. There’s a growing sense of attention and ambition. Not just academicians, but young people with no/limited formal training too are now taking on the arduous task of translating, even though the compensation is barely worth speaking of.

Luckily for me, the offer to translate this novel—and another memoir—came my way. Otherwise, pitching a work to a publisher and securing a contract can be a long and consuming process in itself.

As a translator, I thrive on both the text and its context—for me, the two are inseparable. I spend a great deal of time understanding the author’s worldview, their life, their moment in history.

Because when readers engage with a translation, they’re not just reading a story in another language. They’re entering a different culture, a different history—and it’s my task to make that encounter as honest, as textured, and as alive as possible.

Date 23-07-25