Photography: Arshid Bhim

Photography: Arshid Bhim

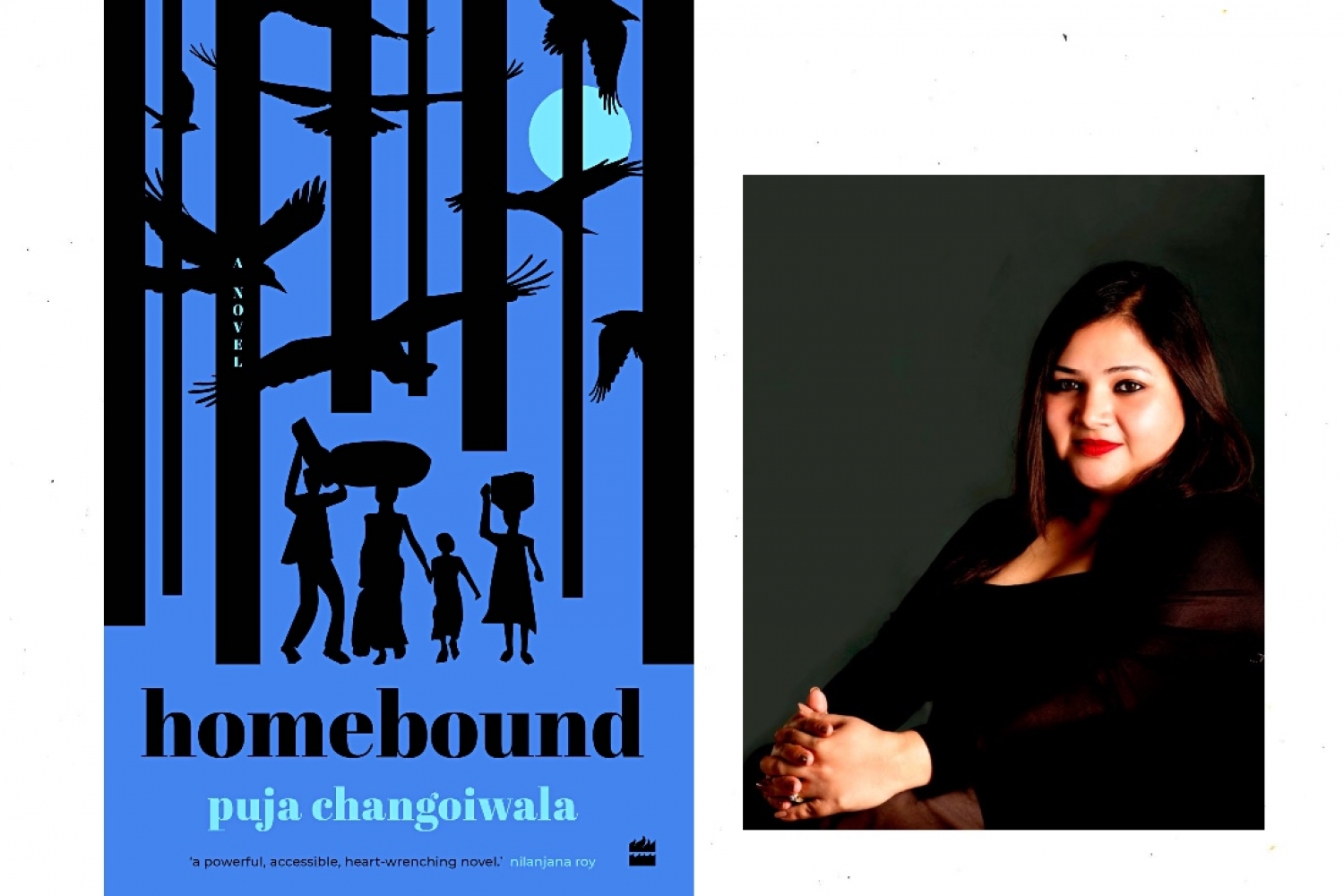

“While becoming a writer was a natural progression of my journalistic career — ‘collateral damage,’ as some would say — I had always wanted to be a journalist. And that long-held desire turned into a resolve after the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks,” shares Puja Changoiwala, an award-winning journalist and author of highly-acclaimed, non-fiction books, Gangster on the Run and The Front Page Murders. Her encounter with the aforementioned tragedy has led her to explore intersections of gender, crime, social justice, human rights and technology in India. So, for her debut fiction book, Homebound, she has endeavoured to capture the mass exodus of migrant workers to their hometowns and villages when the pandemic resultant lockdown hit the country last year. And this endeavour has resulted in perhaps the most important book to emerge from, and on, this dire time. Setting itself apart from the media coverage on this crisis, Homebound fictionalises the very real circumstances of the people by delving deeply into a single family’s, especially their young daughter Meher’s, physical, psychological, and in many ways, a significantly political journey.

“Humans have inspired Homebound, and the novel relays their very real triumphs and their realer defeats. It’s an attempt to capture the hope, resilience and fortitude of India’s invisible workforce — real people who breathe, sense, and feel, and despite the disregard and neglect, continue to dream, hope and believe,” she asserts. Below, the author gives us further insight into this brilliant book’s creation:

THE CONCEPTION

I wrote Homebound because I wanted to document the migrant crisis that followed the Covid-19 lockdown in India last year. I had begun to believe that their exodus belonged to history, with the great journeys triggered by wars, conflicts and natural calamities. As a journalist, who has reported on India’s informal economy and the workers who pillar it, I knew that their plight was to be blamed on the systemic, structural decay that has spanned decades. Exploited and abused since time immemorial, their mass departure had lent them sudden visibility in the national discourse, and now that their obscurity was beginning to dissolve, I wanted to seal their cold realities in ink, ensure that we never drown them into oblivion again.

THE CORE

Homebound traces the journey of a migrant family in Mumbai, who are compelled to walk 900 kilometres to their village in Rajasthan after the state announces the world’s biggest coronavirus lockdown. At the novel’s core are the 450 million internal migrants in India — humans who form the bulwark of our economy, while living in Dickensian tenements, mostly working as daily-wage labourers without safety gear, written contracts, job security, paid leaves, health care benefits, social security, and fair wages.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

As the author of two non-fiction books, my first instinct was to write a true account, relaying the journeys of a few migrant workers as they marched home. Considering the topicality, I had to write the book soon, and with the restrictions on public movement, I knew that wouldn’t be possible. Being an independent journalist, I do not have a press card, and could not travel to villages to meet the characters of my story. The lockdown, thus, turned me to fiction, and filled with doubt, I embraced the risk of failure. This was a crisis that I just had to document.

JOURNALISM AND FICTION

I think fiction, especially contemporary fiction, has an obligation to be friends with reality. My journalism, thus, has only abetted my work as a fiction writer. Although a novel, Homebound borrows heavily from my journalistic fixation on research. For instance, to understand the characters of this book, I visited dozens of villages in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan, sauntering along the road that the migrant workers trudged, and interviewing scores of them. I spoke to NGOs along the way, the families of these birds of passage, and villagers, who saw them as a threat. I spoke to lawyers, police officers, migration specialists, and anyone, who could educate me about their Homeric journeys, the nuances of their lives and their homes, and the structural issues that mar India’s informal workforce.

THE CHALLENGES

Writing Homebound came with many challenges. As I went about creating Meher’s [the 15-year-old narrator of the book] world, I realised that as a writer, I can manage non-fiction, relying on facts for rescue. Fiction, however, challenged me. Fiction despises the creative censorship that walks in with truth, yet demands its reason. It compelled me to peep within, and it exposed demons I did not know I bore. It turned my family and friends into raw material, and it made me feel vulnerable and free, dubious and determined, all at once.

This article is an all exclusive from our November EZ. To read more such articles follow the link here.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 25-11-2021