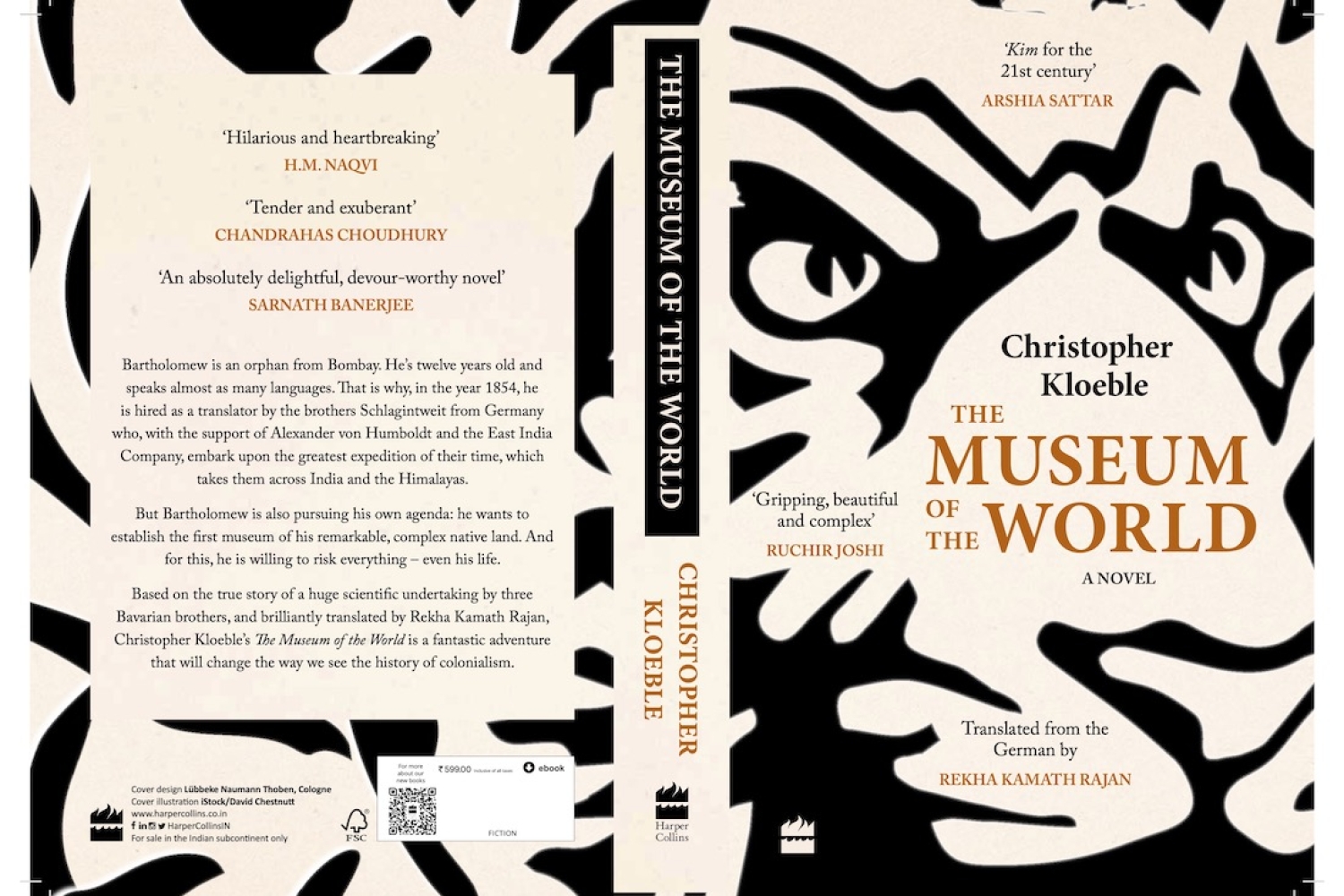

Science, Germans’ role in colonialism, and an Indian’s voice and gaze pervading European literature, are elements that form the core of Christopher Kloeble's The Museum of the World. While originally written in German, the narrator of the book is a young, orphan boy from Bombay, who provides for us a fictional rendering of the true story behind Bavarian brothers Adolph, Hermann and Robert Schlagintweit’s monumental scientific undertaking and expedition in India, with the support of Alexander von Humboldt and the East India Company. Now, the book has been masterfully translated into English by Rekha Kamath Rajan, for a larger Indian readership to discover the lesser known nuances of their colonial history.

We are in conversation with the translator below:

How were you led towards translating The Museum of the World?

I read the novel soon after it appeared; it was initially available only as a Kindle edition on Amazon. When Christopher wrote asking me if I knew of anyone who could translate it into English, I asked him if I could attempt it myself, since I liked the novel so much, and I was keen to try my hand at translating it. The theme of the novel appealed to me because a large part of my research dealt with India in German literature. I also felt that the novel would appeal to readers in India/South Asia. There is a great deal of literature about the British in India, but this is probably the first dealing with Germans in India and therefore needed to be translated into English at least. I loved the twist that the author gives by making an Indian boy the narrator. In this way the tables are turned, and India/Indians, who in European literature were always the object to be observed, described and judged, now become the subjects, while the Europeans are the objects.

Can you take me through your creative process?

For me, the most important aspect of translating literature is to get the rhythm right. It is difficult to explain this, but I think that every work of literature has its own rhythm, its tone, and this is what needs to match in the translation. I read the sentences aloud in German and then the translated English sentence to see if there is a match (of course, this is after reading the entire novel twice!). The humour, the sadness, the anger — all these emotions are conveyed, to my mind, in the rhythm and the tone of the sentence. I hope I have achieved some of what I wanted to!

Did your translation process include conversations with the author?

Since the language is fairly straightforward, there wasn’t much conversation involved. I didn’t really need to ask what he had meant by a particular sentence or word. There were one or two places where there was a play on words in German, which did not work in English, and which I drew attention to as a problem, as were the few Bavarian phrases.

What do you hope the readers take away from this book?

I hope that readers in India enjoy the book, of course, but also gain a new perspective on colonialism. People are generally not aware of the fact that throughout the nineteenth century, even at a time when there was no unified German state and there were no colonies involved, German intellectuals and scientists participated in what I call the European colonial project. The British also used them to explore places where they themselves were not welcome, and they gained from the findings of these German scientists. So, this is new terrain for this kind of literature, and I hope it will be interesting for readers here.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

I have no plans as yet. But I would love to attempt another novel at some point in time.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 29-12-2022