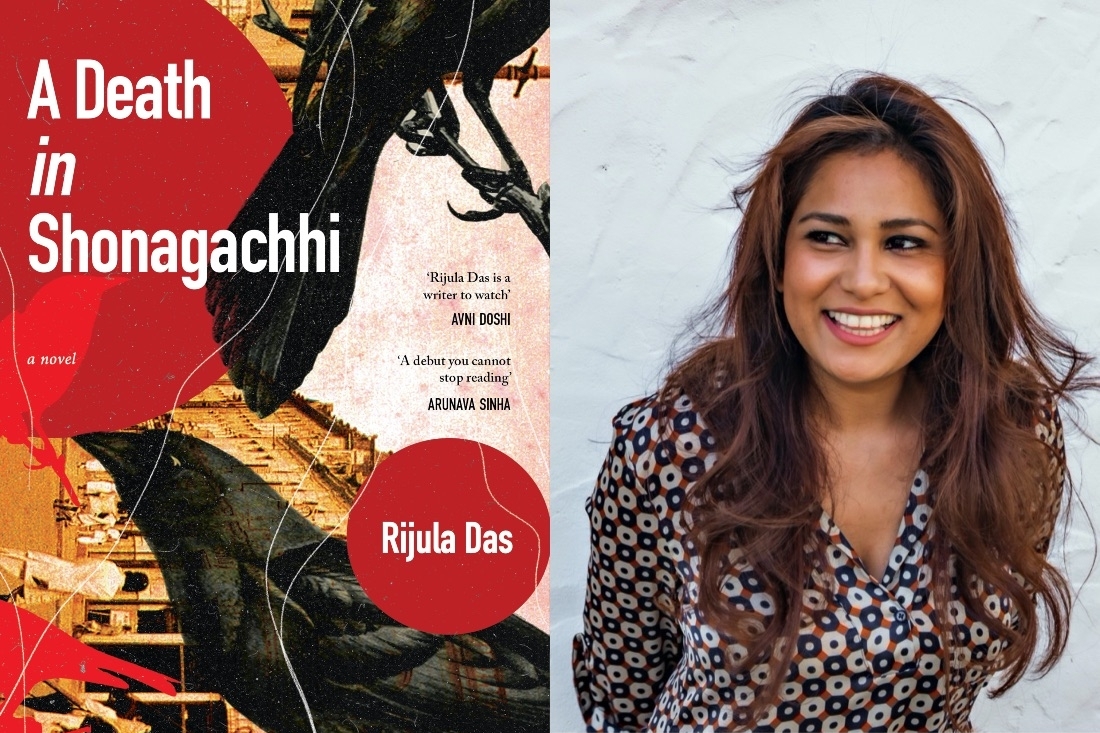

In Rijula Das’ riveting new debut book, the spotlight shifts towards the spaces and people on the periphery, either ignored or continually erased from the city’s collective conscious. The city here is Calcutta, the space is the red-light district of Shonagachhi and the people are Lalee, a sex worker, and Trilokeshwar ‘Tilu’ Shau, an erotic novelist, hopelessly in love with Lalee. And then, the literary noir hits you, as a murder is committed, propelling a series of events that peel through the dreadful layers of the city and the society that occupies it. With A Death in Shonagachhi, author Rijula Das lends us remarkable insight into how our society operates to keep the marginalised on the margins, with ignorance, violence and exploitation.

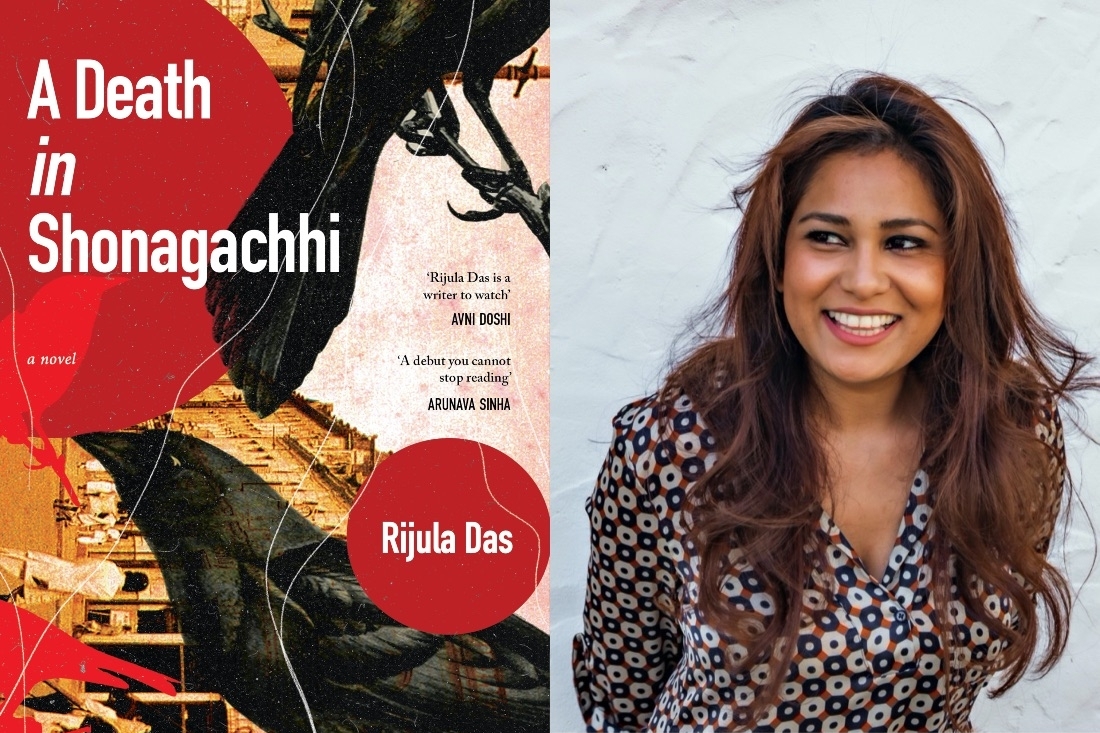

We connected with the author to know more about her and the book. Read our exclusive conversation below:

Why writing?

That is probably the hardest question to answer. All the usual cliches apply to me –– I read a lot, I thought books and writers were magical things, I was a lonely child. But not all bookish, lonely children grow up to be writers. What turns us into writers is a mystery to me. We like to imbue writing with mysticism, but the actual fact of writing can be a fairly humdrum experience. To call oneself a writer, however, takes a certain amount of privilege and arrogance. My socio-economic circumstances didn’t groom me to own that label quite so readily. It was always meant to be a side talent, and the praise of friends was reward enough. Writers have always been writers, there is something in the wiring that’s preset, but it wasn’t till I started my doctoral work in creative writing that I was able to say aloud that I’m a writer. It was thrilling but also very exposing.

Which writers and books that have informed or influenced your work?

I’m a mongrel writer. I read widely and it’s hard to see my own influences, and I suspect they’ll be different for my subsequent work. But for this book, Nabarun Bhattacharya’s spirit of the carnivalesque was a big influence, the nose-thumbing bravado of people who dance on the edge. The humour in this book owes a debt to Terry Pratchett. Both these authors have played with genre expectations and subverted them. I wanted to extend that experiment to the anti-murder mystery, because there are deaths that we let slip through the cracks.

What inspired A Death in Shonagachhi?

I wanted to experiment with form and polyphony. It was an attempt to write a local, regional book, in English, preserving the spirit and form of Bangla literature. I wanted to tell a story that had existed on the margins of our cultural consciousness as exotica, without making it sentimental or pandering to the expectations of tragedy. I also wanted to tell a story that wasn’t personal, a book that looked outwards and not into my own psyche. Mostly, I wanted to see if I could write a book worth reading.

What is at its core?

The core of this book is a community and a city, and their extraordinary everydays. To catch them at the moment of their confrontation with violence and structural negligence.

Could you give us an insight into how you conceived and built the main protagonists?

That was the easiest part. The characters were already there, in a manner of speaking, I didn’t feel I had to create them or their personalities. My characters have always been real people to me, in the same way that strangers on a bus are real, living universes we brush past everyday. Lalee perhaps, took more coaxing than others. She unfurled gradually. The rest muscled their way in without invitation and did whatever they pleased.

The topography is a significant feature of this book. What led you to locate your debut novel in Shonagachhi?

A Death in Shonagachhi derives from my doctoral research, which examines the relationship between public space and sexual violence in India. As a writer, I’ve always been interested in place, in the private spaces we create amidst the public. I wanted to explore Shonagachhi’s continued existence in a country where sex work’s relationship with law and society is difficult at best. It is a very public neighbourhood, but it is also very intimate. I wanted to question why Shonagachhi, a place that has fascinated us for generations, seems to have only a walk-on part in mainstream culture. The book is, in many ways, a love letter to Calcutta. But I was more interested in writing a novel that focused on the margins of the city.

What kind of challenges did you face with the debut?

The greatest challenge was confronting my own mediocrity. I’m a good reader, and I knew, all too starkly, when I disappointed myself. I wasn’t a good enough writer to tell myself a story in the language I needed to. I’d written short fiction before and they’d cost me blood, but I was able to arrange every word, every comma, in exactly the way I needed them to line up. It was difficult to demand that exactness in a novel. It felt too vast, too much flowed through and out of my fingers. I hope, one day, I’ll write a book-length work that will be precisely wrought, that will say no more and no less. But the only way to learn how to write a book, is to actually write one. That is the biggest challenge –– feeling uncertain, and still going anyway.

How have your own roots affected the creation of this book?

I grew up in small-town Bengal. Coming to Calcutta was, in minor ways, an unsettling experience. Moffusil towns take a glamorous view of life in the cities, and then one day you realise that the big city is provincial in its own way. My intimacies with Calcutta have always had an element of distance; I’ve been an outsider in a city my own but not my own. The characters in my book, in their own way, have a deep intimacy and a deep distance from the place they call home. My character Tilu Shau’s perambulations of the city is a very close representation of my days of flaneuring in the city.

What do you hope the readers take away from your work?

It is too early to talk about my ‘work’. I’m only one-book old, and don’t know if I’ll get any older or better. For this book –– I hope they take away the laughter, the humour, the unexpected edges and polyphony of my book’s people. It’s easy to imagine the tragedy of nowhere towns like Shonagachhi from our sanitaire-cordons, but like life and like Calcutta, Shonagachhi has its humour, its slant-eyed mockery, and its defiant laugh in the face of adversity.

Today, what does Calcutta mean to you?

Love. Ask any Bengali, they’ll tell you the same thing. We’re parochial that way, intense, and possessive of the narcissism of our small differences. Calcutta is an impossible city; it is impossible to get through the day without the city overwhelming you, drowning you, soaking you through. I wouldn’t learn how to write if I didn’t fall in love with Calcutta.

How have you been coping with the pandemic and what will be the new normal for you post it?

I think immigrants lug around an invisible oxygen cylinder wherever they go. The oxygen level climbs downwards each year, month, day you’re away from your ‘place’. That place doesn’t have to be a country; it is the soil you belong to. Like some plants are native to a soil, a climate, a certain kind of rain. My oxygen cylinder has run out. I haven’t seen my family and soaked up my ‘place’ in more than two and a half years and counting. I’m very lucky to live in New Zealand, and very lucky that my immediate family in India has been safe through the pandemic. But separation like this leaves invisible wounds and makes it hard to breathe.

The new normal is probably getting used to the concept of digital publicity. If I had had an idea for my first book at all, it would have involved bookstores, meeting readers, just as I’d stood starry-eyed in the back of the crowd, listening to writers in conversation at their book launches. I’ll never write a first book again, but in this ‘new normal’ I can’t meet the people I’d have hoped to meet through this book.

Lastly, what’s next?

I’m working on translating Nabarun Bhattacharya’s novel, Kangal Malshat, from Bengali to English and looking forward to getting on with the next book.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 28-07-2021