Photo Jonathan Ring

Photo Jonathan Ring

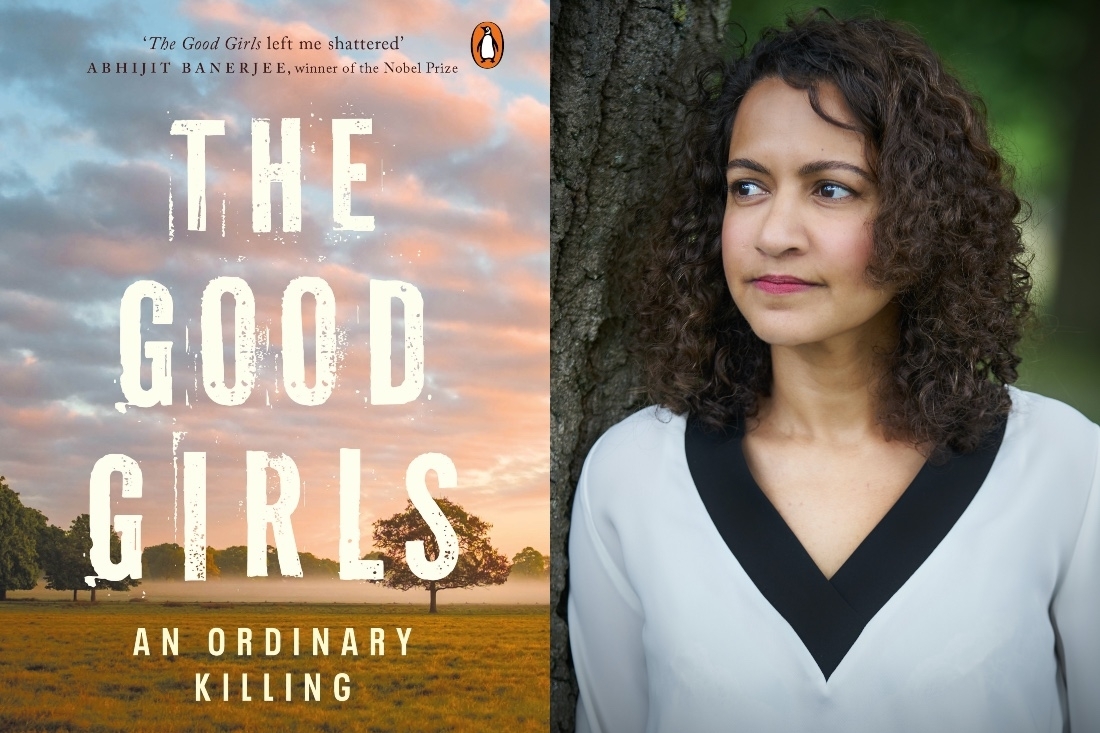

When I began reading Sonia Faleiro’s The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing, I was prepared to be devastated by the narrative reportage. It was clear from the very beginning that this true story about the death of two young girls in a village in Uttar Pradesh, when investigated by the lens and acumen of someone like Sonia Faleiro, would end up revealing all the shades of darkness that pervade our society’s attitude towards women and sexual violence. Needless to say, the tragedy, written in a cleverly empathetic yet unsentimental way by the author, is gut-wrenching and heart breaking. After sixteen-year-old Padma and fourteen-year-old Lalli go missing and hours later are found hanging in the orchard, the investigation into their deaths implode everything that their small community held to be true, and instigate a national conversation about sex and violence. Slipping deftly behind political manoeuvring, caste systems and codes of honour in a village in northern India, The Good Girls returns to the scene of Padma and Lalli's short lives and shameful deaths, and dares to ask: what is the human cost of shame?

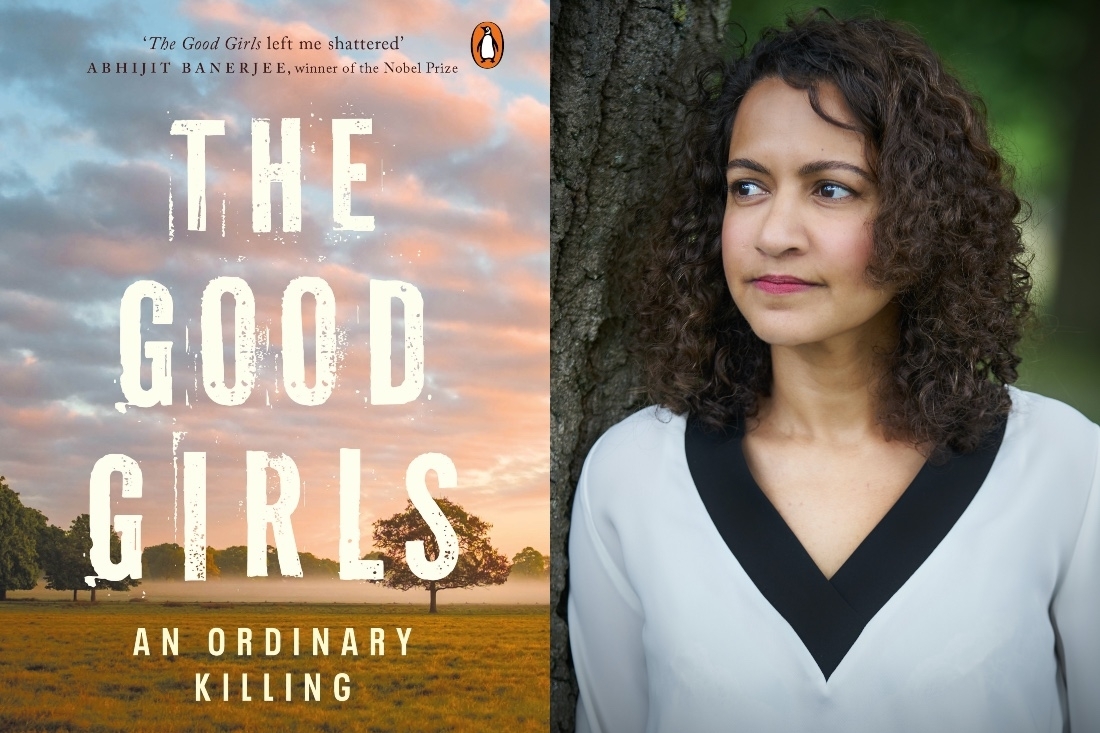

In conversation with Sonia Faleiro about the book and her process behind its construction.

What is your first memory of writing?

I was always writing. I have a lot of notebooks from my childhood. These old-fashioned, A4 sized, ruled notebooks that were called registers, that I would take from my father's office and I would just fill them up as quickly as I got them. At first I was filling them up with stories, which were heavily influenced by the literature I was reading at the time, and later with records. I keep a lot of records, akin to keeping a diary. So I was always precocious in this one way.

How were you led towards the true story behind The Good Girls and what made you want to write a book about it?

Just like pretty much everyone else outside Katra Sadatganj, where this incident occurred, I was introduced to it by an image circulating on Twitter. The image showed the children hanging from a tree, and it was taken by a reporter who was a local and had gone to the orchard in the morning. He took the picture and posted it on Facebook, where I don’t believe it elicited the reaction the way it did on Twitter. When the photograph migrated on Twitter it created an uproar and the immediate rumour that began circulating was that the children had been raped, killed and then hanged by a man from a dominant caste. This was merely two years after the 2012 Delhi bus gangrape case, which had a profound impact on me and prompted me to look into the subject of sexual violence in India.

When the Katra Sadatganj incident took place, I thought I would use that incident in my book. However it was just going to be one incident and I was going to write about a great deal of other things. I flew to Delhi, went to Badaun, stayed there in a hotel and then drove a couple of hours more to get to Katra Sadatganj. I ended up staying a few days in Badaun and at the end of that week it was quite clear to me that the story of what I had been told and what I had read was not the full story of what had happened. So I was faced with the choice of whether I want to write what I’m being told by the people, or if I want to investigate, and I decided to investigate the case.

As unsettling as the events described in the book are, the narratorial tone of you writing tends to remain calm and composed throughout. Could you give us an insight into your process behind writing this book?

The Good Girls is very much in keeping with how I write. You’re right that it is calm and composed, and I am not present in the text. I don’t offer opinions and absolutely no judgement because I don’t consider that my job. I think my job is to report a story and to present the facts, and that is what I’ve done. I am very serious about this because I feel editorialising is unnecessary. I don’t think it achieves any purpose and very likely puts-off people. I prefer that the readers make their own judgements, come to their own conclusions, and I think that is a part of the process. I remember that I was asked by an editor if I would like to be a character in the book, but I never seriously considered that.

The book is seeped in darkness and is an important exercise in the exploration of violence and suffering. How challenging was it to delve into such dark themes?

It is a struggle to work on a project such as this, and not just for a few months but for several years. The story of The Good Girls is particularly tragic and moving because it involves children and I was dealing with subjects who were traumatised for obvious reasons. So it is impossible not to be moved by that level of suffering. I am affected by these things but I try not to focus on them. I focus on the work and I remind myself that ultimately I am a bystander. I mustn’t respond in a way or write in a way that takes attention away from the people whom I am writing about and brings it on me. With that in mind I tend to work.

As there are many many social and cultural concerns at play in the book, did you have any one, perhaps main driving force while writing the book?

Just trying to understand what had happened to the children. It really is remarkable that there were so many people involved in the incident of the night when the children disappeared. They left their house ostensibly to go to the fields to squat and didn’t return. Then one search party and then another went looking for them. Dozens of people were involved, then the police was involved, and all of this happened even before the sun had risen. Afterwards of course the politicians showed up and the media showed up, and family and friends from far and away. Now you would expect that there would be a single narrative after all this, but there wasn’t. Virtually everybody who went in search of the girls appeared to have seen something different, heard something different and experienced something different. So trying to understand why this was the case was really the first challenge. Once I explored what was happening and why people felt the need to change their stories, then I was better placed to move forward, start corroborating the various stories, and come up with one narrative.

The book begins with an epigraph from The Laws of Manu. Could you elucidate upon the significance of this epigraph?

It offers an insight into how women are perceived. We all understand that adults should have the freedom to live their lives as they please and it really doesn’t concern anybody else unless they aren’t breaking any laws. However, what we continue to see in many parts of India and the world is that a woman’s life, even if that woman is an adult, is considered everybody’s business. Whether it is family or partners or society at large, everybody feels this need to comment on, judge, and tell women how to be. I find this extraordinary, given how we’ve advanced in so many other ways and yet we continue to be so backward in this one fundamental way. We do not allow women to live freely. I also don’t think this problem is only exclusive to rural communities and what we see with The Good Girls is that it has a terrible effect on the development of young girls. It destroys their hopes, it shatters their dreams, and ultimately in some cases, like this one, it can have a deadly effect.

What do you hope the readers take away from this book?

I hope it helps them understand the human cost of what we seem to think is acceptable behaviour. We talk about patriarchy, caste and gender, and sometimes we get lost in the language without realising that real people are falling tragically victims to these social and cultural situations, and we really need to respond in an urgent fashion.

Lastly, how have you been coping with the pandemic and what are you working on next?

I started running again. I run a lot! I am in London and the government has handled the situation perhaps worse than any other government, excluding the United States. We have lurched from one lockdown to the other without really knowing what is happening. None of us know what lies ahead and one way I’ve found of coping with the anxiety and stress is to just run. It helps me start my day and just smoothes the edges. I am also trying to be kind to myself, to the people around me, and taking it all one day at a time. The other thing I do is just focus on work and I am now figuring out the idea behind my next book.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 28-01-2021