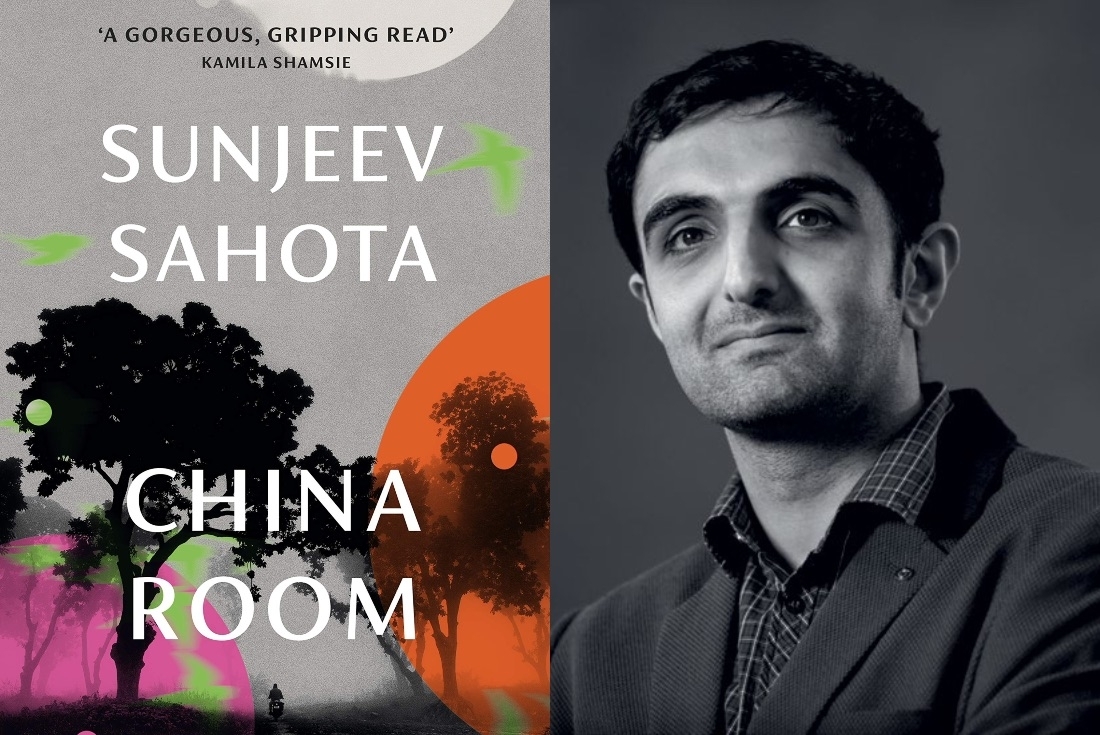

At the end of Sunjeev Sahota’s new book, China Room, now longlisted for the Booker Prize 2021, there is a photograph of a lady holding a baby. Upon probing, the writer tells me that it is his great grandmother holding him, around the time he was born. The photograph is a significant aspect of the book, as the writer himself asserts. China Room’s narrative ricochets between the story of an unnamed narrator in England, battling his sorrows and addiction, and of Mehar, a newly-wed young woman, living confined within a room called the China Room, on a large farm in rural Punjab. The stories, also set in two very different time periods, find themselves constantly reverberating each other. Eventually they collide and a deep-seated connection comes to fore. This connection finds itself encapsulated in the photo, as the author’s great grandmother’s story was the inspiration behind China Room.

We connected with Sunjeev Sahota to know more. Excerpts follow:

From your debut book, Ours are the Streets to the recent release of China Room, it has been a decade. How has your craft evolved in these past ten years?

I think some commonalities are still there in terms of language and the intimacy between my characters. In this particular book, China Room, there is a greater emphasis on the form and how the emotions and thematic interests in the book can be delivered via the form and structure of the novel and not just through the characters. I was always interested in the framework of a book, so perhaps in this book there is a greater focus on the artistry of the novel writing process.

What does writing mean to you after all these years?

I love writing. I am completely absorbed by it. Even when it is not going well, it is still something I love doing. It is a very nourishing relationship. I derive a lot of meaning from reading and writing. It is where I feel very the most comfortable and alive. I feel at home.

In your three books so far, do you feel yourself gravitating towards certain thematic concerns?

Across all my novels, all my characters seem to be seeking some kind of freedom, liberation and connection. Whether it was in my first novel, about a young man in the north of England, who is trying to find a sense of who he is and liberation from the constraining sense of himself that he has. Or in my second novel, where the characters are literally trying to escape in search of a better life. In China Room, both the main characters are oppressed by society. They are oppressed in different ways but they are both seeking liberation and connection. It was a really interesting idea that not only are these stories connected thematically, but one of the themes is also them looking for connections. So form and content really aligns for me in this book.

What inspired China Room?

There has always been this family legend about a great grandmother of mine, who was, as the story goes, one of four women married to one of four brothers, but did not know which brother was her husband because they were all veiled all the time and had to be kept sequestered. They did not know until a year later, when they saw which husband was holding their baby. I don’t know how much of this story has changed over the years and how much truth there is in it now, but this was kind of the seed of the story in China Room. I took this seed a began to wrap it with a fictional narrative. However, five-six thousand words in, I stopped writing the story. It didn’t feel vital or necessary for me to be telling this particular story. I started writing a different story. It was about an unnamed narrator, going through his own kind of pain and trauma.

Then I realised that these two stories have so many things in common. So many themes echoed, so many mirrorings. I soon recognised that they were both a part of a larger story. I started writing the story of my grandmother again alongside the story of the unnamed narrator, who then ended up being his great grandson.

Addiction is a significant theme in this book. What drew you towards exploring it?

I think what draws the young man in the novel towards addiction is the fact that he can give form to his pain and trauma in this way. The pain he feels and his difficulties are quite abstract. One of the ways he can make sense of it is by putting it all in a vial or a syringe. He can see it and say that this my pain. This is how I can hold my pain in my hands, via this addiction. Which is why I think for this character and for many, addiction is a way of housing your existential sadnesses. By giving it form and then overcoming his pain, he is trying to overcome his addiction as well.

Were there any particular literary influences that affected the creation of this book?

Henry James’ A Portrait of A Lady is a story of a young woman fighting to forge her own path, so there are parallels from that book with the stories about female characters like Mehar in China Room. Also Edith Wharton, in her books The Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth, is very interested in the idea of triangulated dynamics and my novel also has many threes and triangles, which very much ground the novel. Then José Saramago wrote the book The Double about a doppelgänger, and I started this book with that sort of idea. In this book, the doppelgänger became like a version of me, which I thought was an interesting kind of transmutation as well.

If you could iterate, what would you like the readers to take away from this book?

There is a line towards the end of the book that says ‘the underlying hurt cannot go away and can only be paid attention to’. Pay attention to your pain. There is no total redemption ever. All you can do is make space for that pain and move forward regardless. The book is also asking for a distinction to be made between accepting pain when we need to, but that doesn’t mean that we judge that pain to be acceptable.

The farm in India has a significant topological and thematic place in the novel. What kind of a relationship do you share with India personally?

I miss India! I used to visit India every year, but I haven’t been to India now in four years because my children are quite little and then the pandemic hit. I’ve got a large family there. The farm that the story is set in, that’s my family farm and it is still there. I love that while I am walking there, even though I don’t speak the language fluently, there is a kind of freedom. You become kind of oblivious to what everyone is saying. Here in England, I hear everything and I understand everything, and it can be a bit oppressive. In India, I love the cacophony and just existing in a place without totally being a part of it.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

My next novel, it is quite early to speak of it right now, but it is looking like it’ll take on the idea of the doppelgänger with a very surreal tone. The idea of the doppelgänger is a potent image, which really intrigues me. I am hoping the writing of the novel will explain to me why it intrigues me.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 29-07-2021