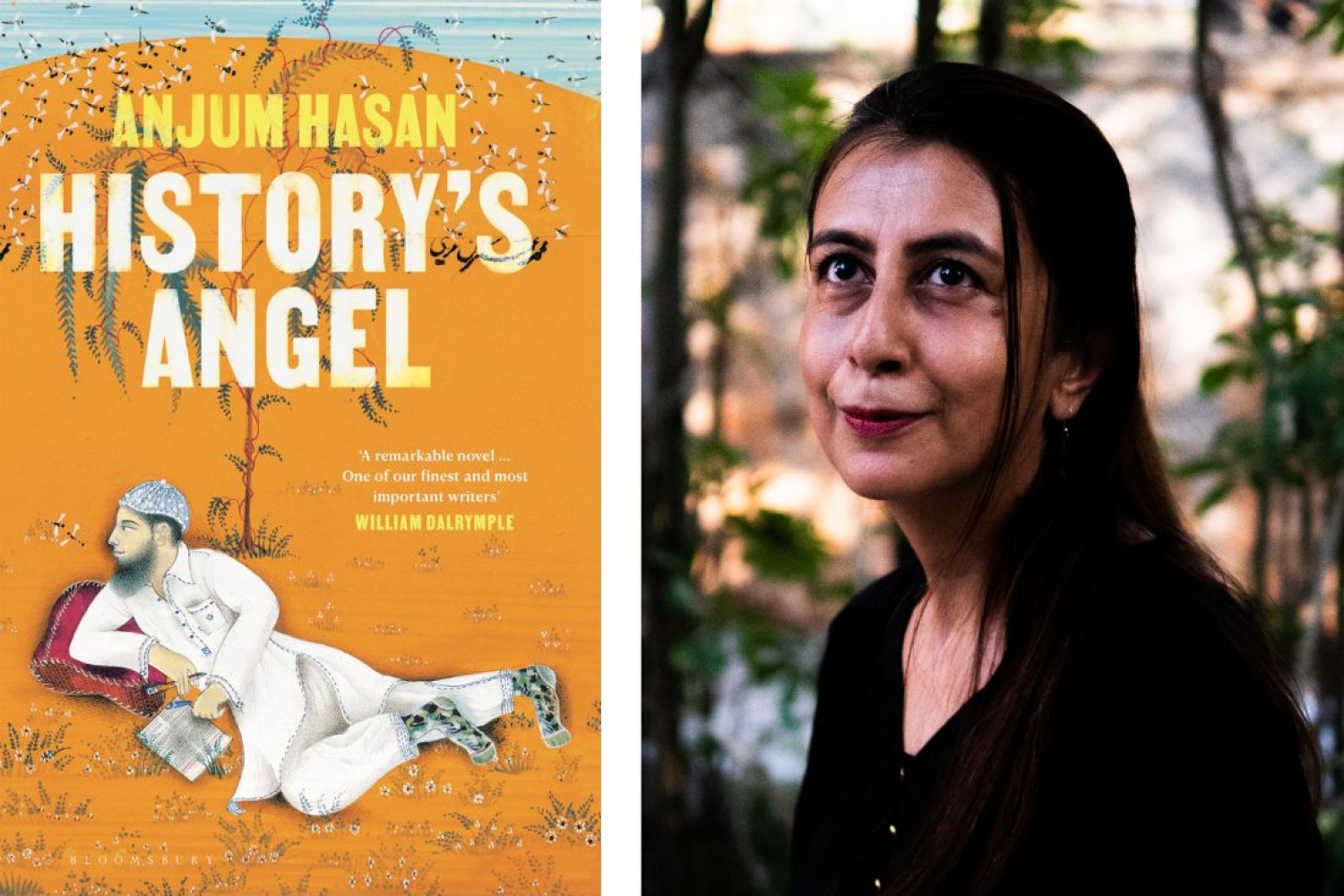

In her latest fiction, History’s Angel, Anjum Hasan depicts how history is itself fictionalised in the times we live in. Through the fragments of polarisation, Hasan’s protagonist, Alif, navigates life as a Muslim history school teacher in Delhi. Alif grapples with the challenges of the Indian education system, where rote memorization overshadows a genuine understanding of history’s significance.

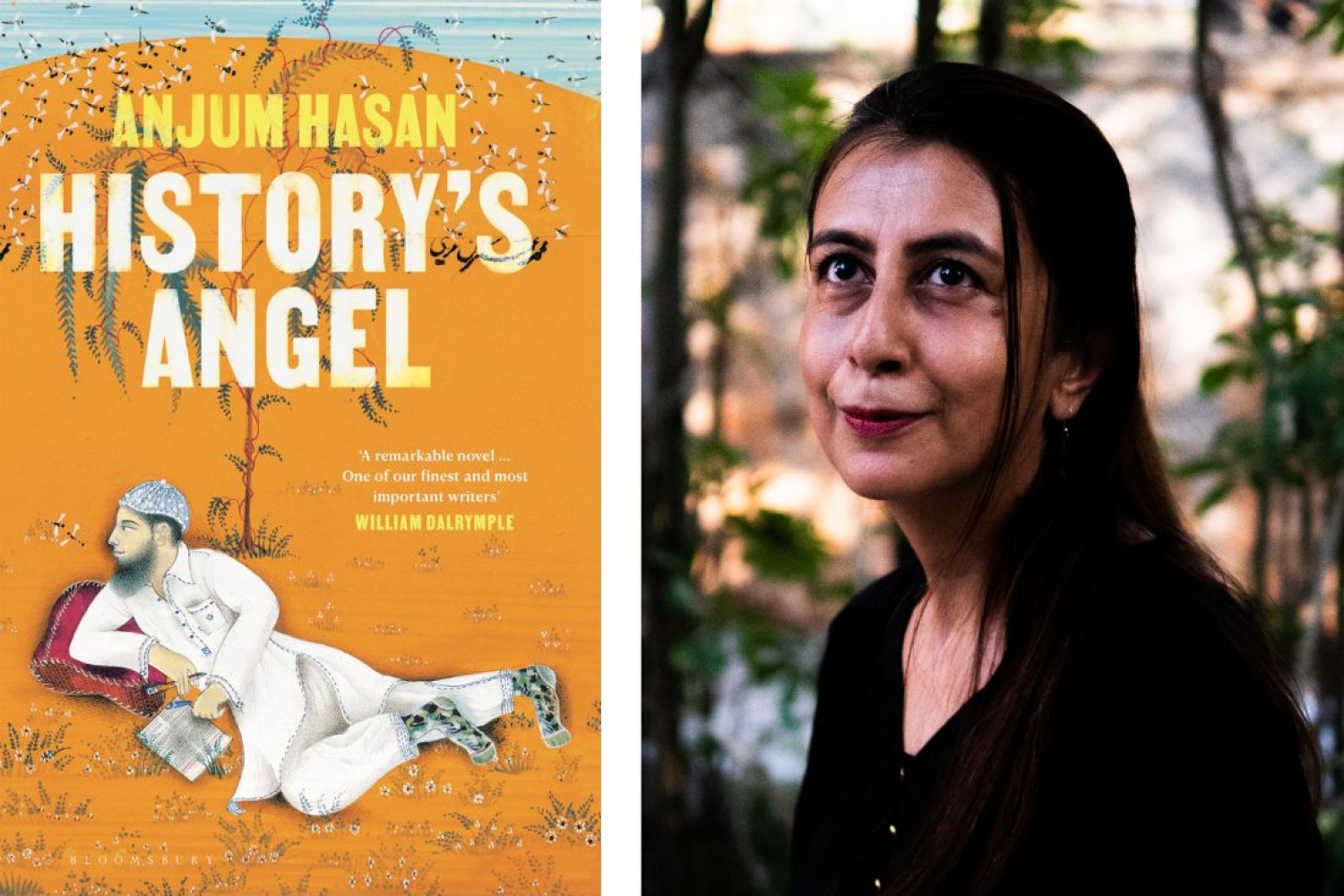

While he aspires to live a simple life where all he wants is to make children understand history in all its complexity, his wife, Tahira, wants to complete her MBA and make a name for herself in the structure of capitalism. Through wit and compassion, Hasan’s book stands out as one of the essential records of contemporary India. In this conversation, Hasan talks about her creative process, the intricacies of her characters, and the artful manner in which she weaves together her prose to tell the story of an ordinary man navigating the complexities of past and present .

What made you come up with a protagonist who is obsessed with history?

A protagonist taken with history, that is, with a critical view of history, in an Indian novel is by default a standout. History passes very quickly into myth in our minds – e.g. Gandhi as a Mahatma. Or it becomes emotively political without sufficient attention paid to the facts – e.g. our long-running obsession with the temple and mosque. Both of these attitudes Alif, my hero, would deplore. He is both passionate about history and impersonal about it, that is, he doesn’t take anything in the march of the ages personally.

What were the challenges of writing this novel?

To not bore the reader – because one is writing about recent things, things very close to home, which are done to death in the media already. To make beauty out of con- temporary dreariness, which is only possible by trying to keep the language alive and dancing somehow, oppose it to the language of the media. To not be partisan, to show all the wrong-doers on every side as equally human or equally inhuman.

What significance does the poetics of Urdu hold in the novel?

I know very little Urdu poetry, just small scraps, and everything I knew I put in the novel. The characters know much more. But it fascinates me – poetry as part of one’s frame of reference. It does something to the worldview. Makes it otherworldly and ironical.

Did writing this novel bring change to you or your understanding of society?

It helped me deal with the times. I don’t have well-formed political opinions – and don’t want to take part in the debates of the day. But the tone in which the debates are conducted, how the shouting on the TV sounds, or how fear and loathing are expressed in private conversation – now that’s of interest.

What do you hope readers take away from this novel?

The sense that fiction can speak to the feelings we are all feeling. I still believe there is redemption in being able to talk about dark times – and I don’t believe the times are entirely dark. But I also hope that we can think more about things like form and style and not see novels as just dry reports on what’s happening. We are impatient with literary questions and I want to ask literary questions, while all the time telling a story, of course.

Alif and Tahira’s aspirations differ from each other, what sort of complexities did you want to explore through their relationship?

I think difference of opinion in a marriage is par for the course but divergent values are trickier. I thought of Tahira, when I was starting, as just a routine example of the age of discontentment and the age of consumption but she turned out more alive than that. As I developed her in contrast to Alif, she became a high-spirited woman and a practical one. The question I’m asking is: can love overcome even such differences? How does love play out under the pressures of the times?

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 17.02.2024