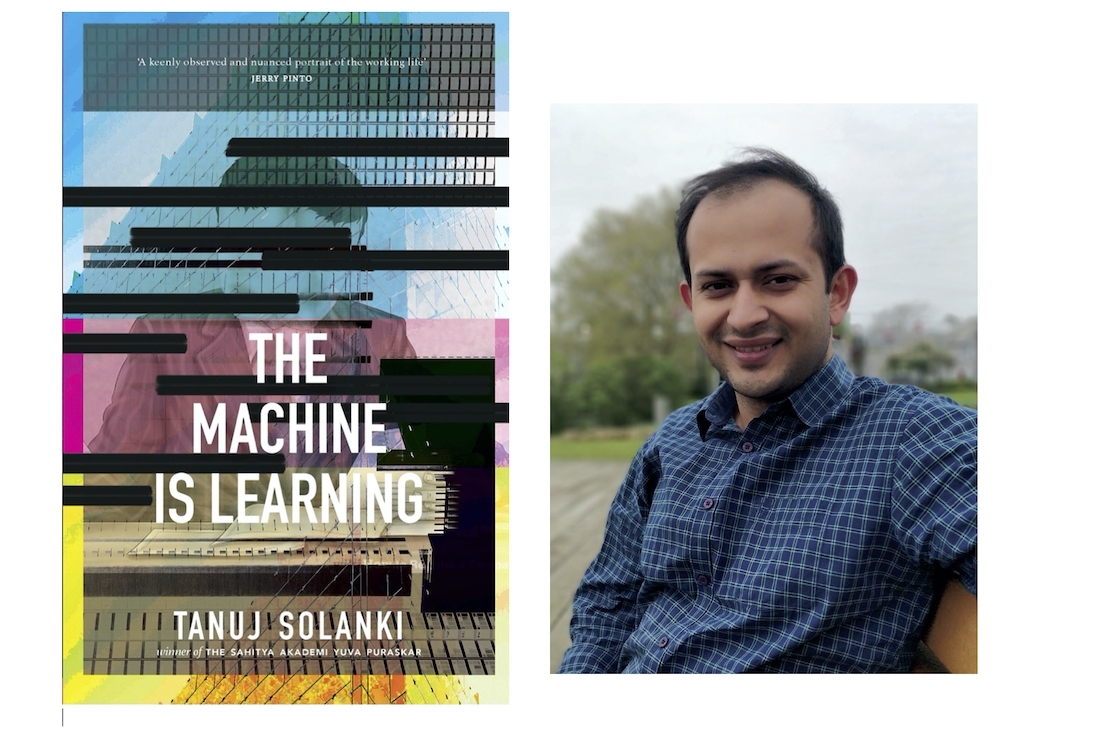

Saransh works at a life insurance company, as part of the Special Projects Group (SPG). Their current project is top-secret: the development of an Artificial Intelligence system that will leave 552 branch-level employees redundant overnight. Because of site-specific customizations, however, the system needs to collect information from the company’s various branches. Thus begins a cycle in which Saransh travels across the country, interviewing the very people that his machine will replace soon.

The Machine is Learning is a novel about twenty-first-century workplaces, love and the impact of technology in all of our lives. It interrogates a world order that accommodates guilt but offers no truly ethical course correction. In the nexus of capitalism and technological advancement, the value of human life is slowly dissipating. Tanuj’s book explores this lesser acknowledged side of capitalism — one that is apathetic to the devastation it causes.

In conversation with the author about his literary journey, the new book and the pandemic.

How were you led towards the world of writing?

By the urge to imitate good writing. About ten years ago, when I was in my early twenties, I used to read stories in The New Yorker and think 'This is so easy, I should try.’ So I started writing short stories on a whim, or, rather, to match the writers publishing in The New Yorker during those days. Soon I realized that it wasn’t as easy as I had thought. In time, I realized that it wasn’t easy at all. However, through those early efforts, I discovered the joy in writing and rewriting, which stuck.

Which authors and books were your early formative influences?

I’m an early-stage writer, so to speak, and in that sense, all my influences are still formative. I started writing during the Roberto Bolaño boom and his influence was pretty much unavoidable, especially for someone who got attracted to literature by reading American magazines online. My reading-to-learn-writing range has expanded widely since then. I was deeply influenced, I remember, by Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment. Lately, I’ve been amazed by Anjum Hasan’s The Cosmopolitans and I keep coming back to it as a sort of milestone in 21st-century Indian writing in English. One day it is the Nehruvian-enclave novel signing off. The next day it is an adaptation of Don Quixote. Even its faults are dear to me. I hope to one day to write something as accomplished.

What inspired the writing of The Machine is Learning?

I would have to say that it was the Netflix show Mindhunter, which to me was a show about work before anything else. It gave me the template that my novel uses in its beginning: two men traveling across the country as part of their work, interviewing people that they want to eliminate. The context couldn’t be more different from the story in my head, of course, but the first spark of The Machine is Learning came from Mindhunter.

Could you take us through your writing process behind this book?

The plot and the basic storyline was in my head from the beginning. I also had this vague idea about precision, that the novel should be ten chapters of twenty-five pages each. This allowed me to jump across chapters while writing, which was helpful if I was getting stuck at a particular place — I could always hop to another problem elsewhere. This sort of hopping-through-the-plot was happening for the first time in my writing process, and so it was quite fun early on. However as more of the novel filled up, I had to go back to a more or less linear way of writing, wherein I finished page 75 before page 76 and so on.

Your book presents a rare view of the actual effect capitalism and development has on humanity. How challenging was it to tackle such issues in the context of a world that is consumed in ‘techno-capitalist progress’?

Aesthetically and ethically, it was important for the novel not to embrace easy ideological solutions, but to stay with the questions. That has been my attempt in writing this novel. The Machine is Learning is about the onset of mass loss of employment due to technological advances, and therefore about the apathy inherent in Capitalism. Yet, both the novelist and the protagonist completely accept that there is no easy solution. Leave aside solving the problem, it is difficult to even resist the effects purely and without contradiction. Capitalist modes are so pervasive and totalitarian that resistance also falls back into the same pit, both linguistically and materially. In the does-anything-change-in-the-story calculation, The Machine is Learning is a pessimistic novel. However, it does try to find value even in the seemingly ineffectual modes of rebellion that, often, are all that common citizens can muster, and is, in that sense, hopeful.

What do you wish the readers take away from your work?

That Capitalism is broken, and that the possibility of a fix is an urgent matter.

Everyone had been affected by the global pandemic we’re in the midst of, how have you been coping with the pandemic personally?

I’m fine. Work has seeped into my most personal spaces, including my reading-writing spaces. This has caused disruptions that I’ve still not completely come to terms with, but materially I’m fine and find myself able to act, so as to minimize my exposure to the virus — which is also to say that I live in an astonishing state of privilege.

What will be the new normal for you post the pandemic?

I don’t know. I work in insurance. Maybe I won’t need to go to the office as often as I did earlier. Or maybe I’ll lose my job, in which case the question changes in meaning drastically.

Lastly, what is next for you?

In writing terms, if I survive the pandemic and all that, I’d like to work on a big crime novel based in Muzaffarnagar, my hometown. I’m also working on a novella in Hindi, let’s see where that goes.

Text Nidhi Verma