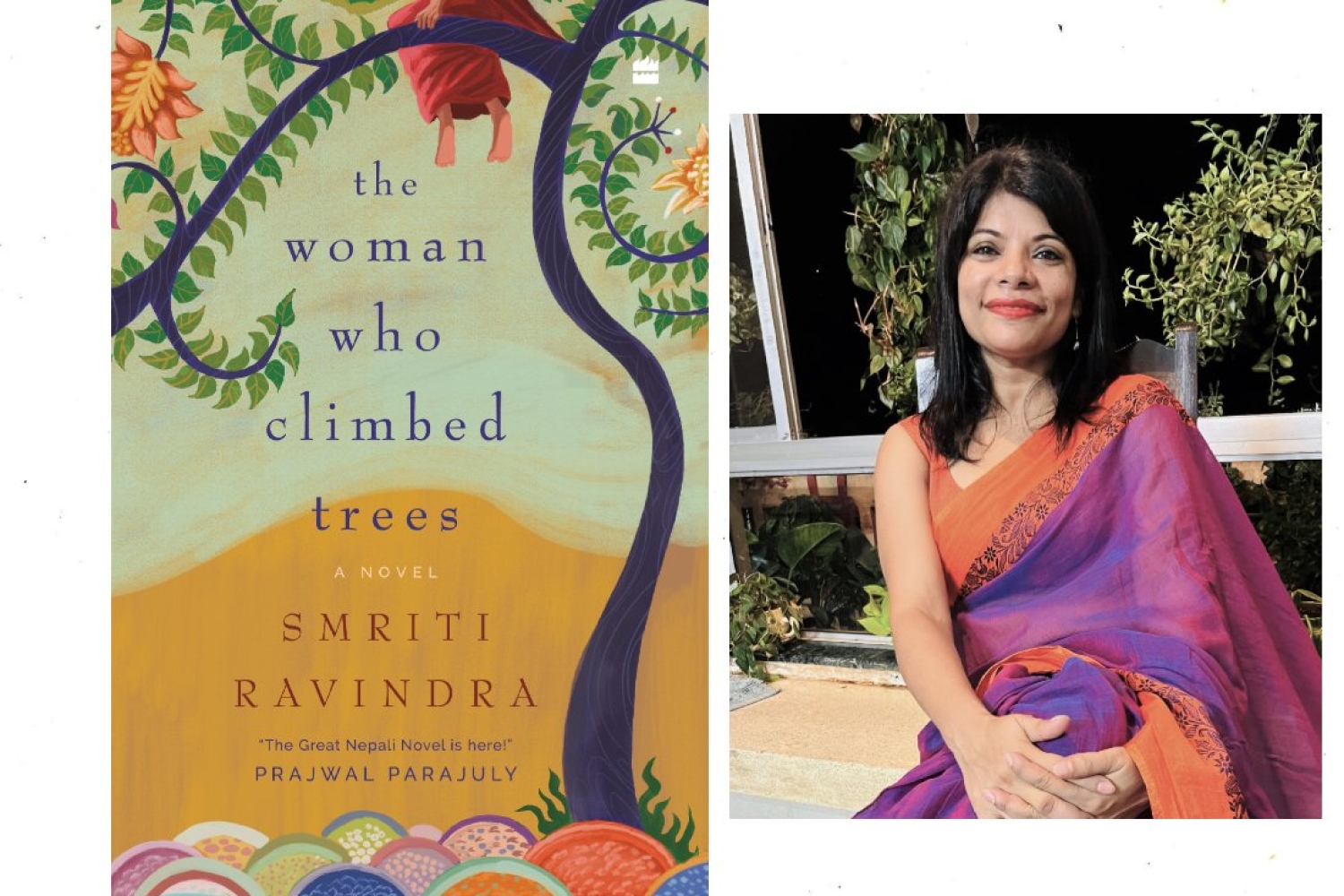

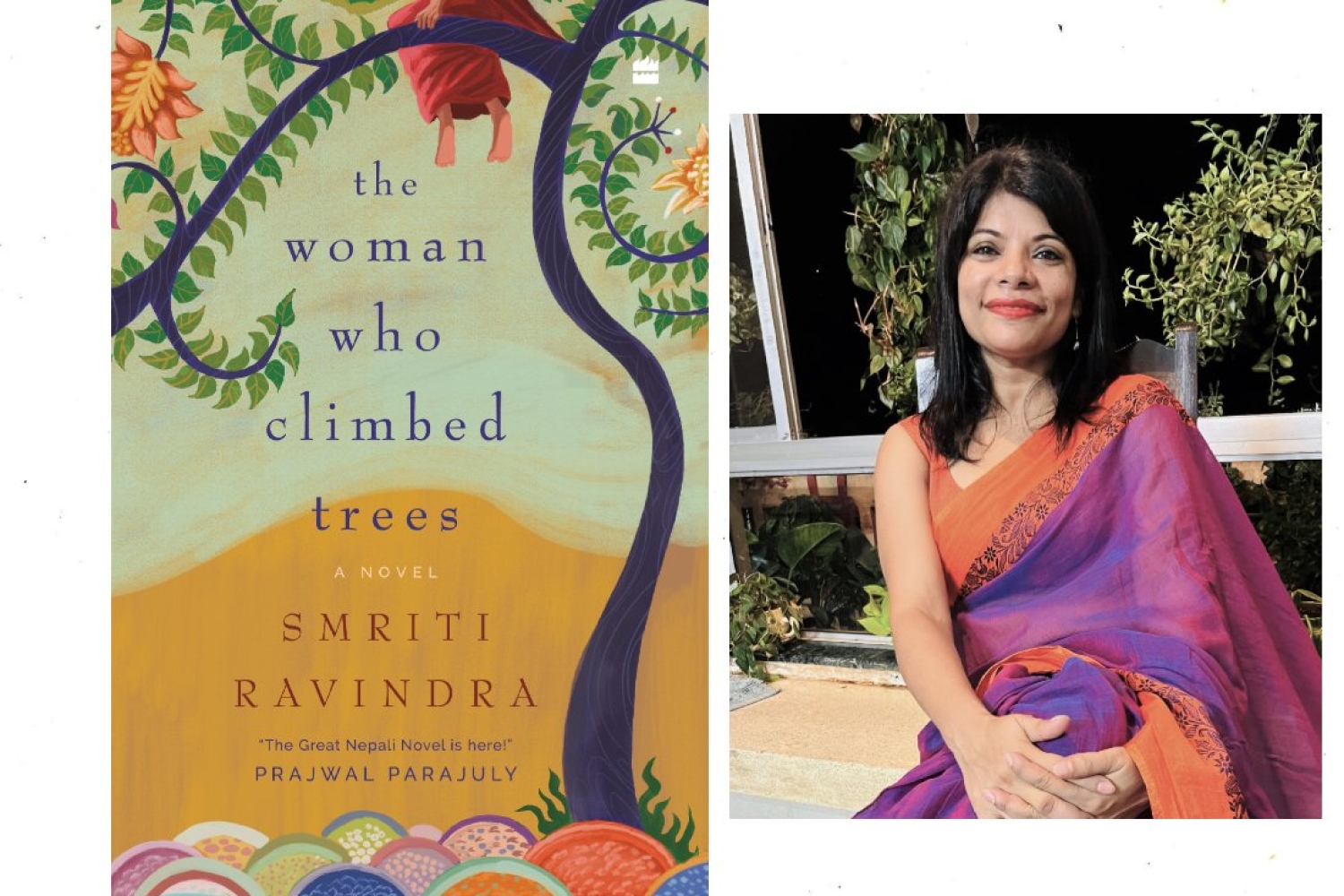

"The Woman Who Climbed Trees did not start off as a novel. It started as a journal. After my mother passed I began a journal where I would write about her. This was my way of talking to her…and for a few years that was all it was, a journal where I tried to capture her voice, understand her situation, imagine her life…and slowly the idea of a book began to take shape. The journal does not feature directly in The Woman now, but its voice, its sentiment does. What Meena feels after Kaveri dies is what I felt after my mother did, and the desire to both keep in touch with my mom and to understand her is at the heart of the novel,” acquaints us Smriti Ravindra to her debut novel, that also pays “homage to the incredible land of stories and myths that these countries (India and Nepal) are.”

Read more from our interview with the author of The Woman Who Climbed Trees, which is being touted as one of the finest literary debuts of the past few years, below.

What led you toward writing?

Hmmm…the lure of pocket money! When I was still in school my father introduced me to the then editor of the newspaper, The Rising Nepal, and out of kindness the editor welcomed me to contribute to the children’s section of the paper. You will even get paid, he said, and so I jumped in. I was, for several years after that, a regular contributor. If I liked a skirt, I wrote. If I wanted a pastry, I wrote. If I wanted to watch a movie with friends, I wrote. It was wonderful! And in the process I discovered that I actually enjoyed writing.

Could you give us a blurb on The Woman Who Climbed Trees in your own words?

Set partly in the late 80s and early 90s of Kathmandu, when Nepal was going through some strong political transitions, The Woman Who Climbed Trees tells the story of Meena, an Indian girl who marries a Nepali man and moves from India into Nepal. The book looks at the diasporic experiences of most women who leave their parent’s familiar homes to enter the expectations of their marital homes, and in the process become strangers to their own selves, and outsiders in both settings. In Meena’s case, she experiences double diaspora because she has also changed nations. Her life takes place within a changing Nepal and is impacted by its socio-political culture.

What led you to locate your debut writing in the novel’s context, and what was your creative process like behind writing it?

Like I said earlier, The Woman Who Climbed Trees was my way of trying to understand my mother, which means too that it was my way to understand and explore the relationship between Nepal and India. As I wrote I realised that there was so much I wanted to talk about. Growing up Madhesi in Nepal is its own experience, and I wanted to capture that experience. I also wanted to pay homage to the incredible land of stories and myths that these countries are. Essentially, I wanted it all, and the novel seemed like the best option. Also the genre allowed me the flexibility to embed other genres within it — like songs, like poetry, like mythical tales. It made space for multiple voices and perspectives. The novel can allow for immense freedom, and this freedom fed my creative process. If I woke up with a song in me, I wrote a song; if I woke up angry, I ranted.

Were there any influences, literary or otherwise, that guided your creation of this narrative?

I was enrolled in an MFA program at NCSU when I began the book, so yes, there were many influences that guided the creation of this narrative. My professors and my classmates were my first readers. They gave me my first feedback, my first encouragement. My first a-ha moments came from them. Since I had no clue then, or until two years ago, whether the novel would ever be published, I sent bits and parts of it to magazines and papers all over the world and every acceptance was a huge boost to my confidence. The submissions also honed my ability to write shorter, tighter pieces.

At one point in my writing, I encountered Maxine Hong Kingston’s memoir, The Woman Warrior, and was stunned by it. I was fascinated by how Kingston wove myths and legends into her narrative, and I tried my hand at it instantly. Another book that took my breath away during the novel’s formative years was The Hours by Michael Cunningham. I was struck by the intensely internal lives of the women in the novel. But my greatest influence came from my extended family in the Mithila regions of Nepal and India. Maithil women are excellent storytellers. They have a story for every occasion, every event in life. My mousis (aunts) tell stories, sing songs, and narrate gossip with a flair that is incredible to me. Their voice is the one I carry inside me and try to recreate.

There are many writers I admire, but I must mention one in particular, not because she shaped this particular narrative, but because I learnt something fundamental about writing from her. Annie Zaidi, the author of Prelude To A Riot and Bread, Cement, Cactus, was my roommate in Sophia College, Ajmer, where we were pursuing our BA. She was a prolific and an amazing writer even then, and every time I read her works I recognised with awe the authenticity of her voice. All her works were so true to her experiences. It was thrilling. I think I learnt to write by reading Annie’s works. I learnt from her that the best is rooted inside you and around you.

Also, I am a Teraian who grew up in Kathmandu. My mother is from Darbhanga and married into Kathmandu. My father’s ancestral home is in Sabaila. The stories I tell are the stories of such people.

What kind of challenges did you face with this debut venture?

I think carving out time was one of the strongest challenges. I had a young child when I started thinking about the book, and now I have a teenage son, an aging in-law, and a full-time job as a high school teacher. In all of this, writing a novel can be overwhelming. The pandemic was the time I really packed things together. The other big challenge was the vacuum I was writing in. Once my MFA was over, my family shifted to Mumbai and I found myself writing alone, with no one to share my work with. Adjusting to this took some time.

What do you hope the readers take away from the book?

Other than the pleasure of reading, I hope there is some appreciation for the things I am talking about. Women and their isolation, for instance. Their mental health. The Indo-Nepal dynamics. The power of sisterhood. I really hope readers enjoy the folktales and myths in the book. Writing them was tremendous fun.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

It’s another novel…at least that is what I think it is so far. I also want to try some children’s stories, so there is that too.

Words Nidhi Verma

Date 25-05-2023