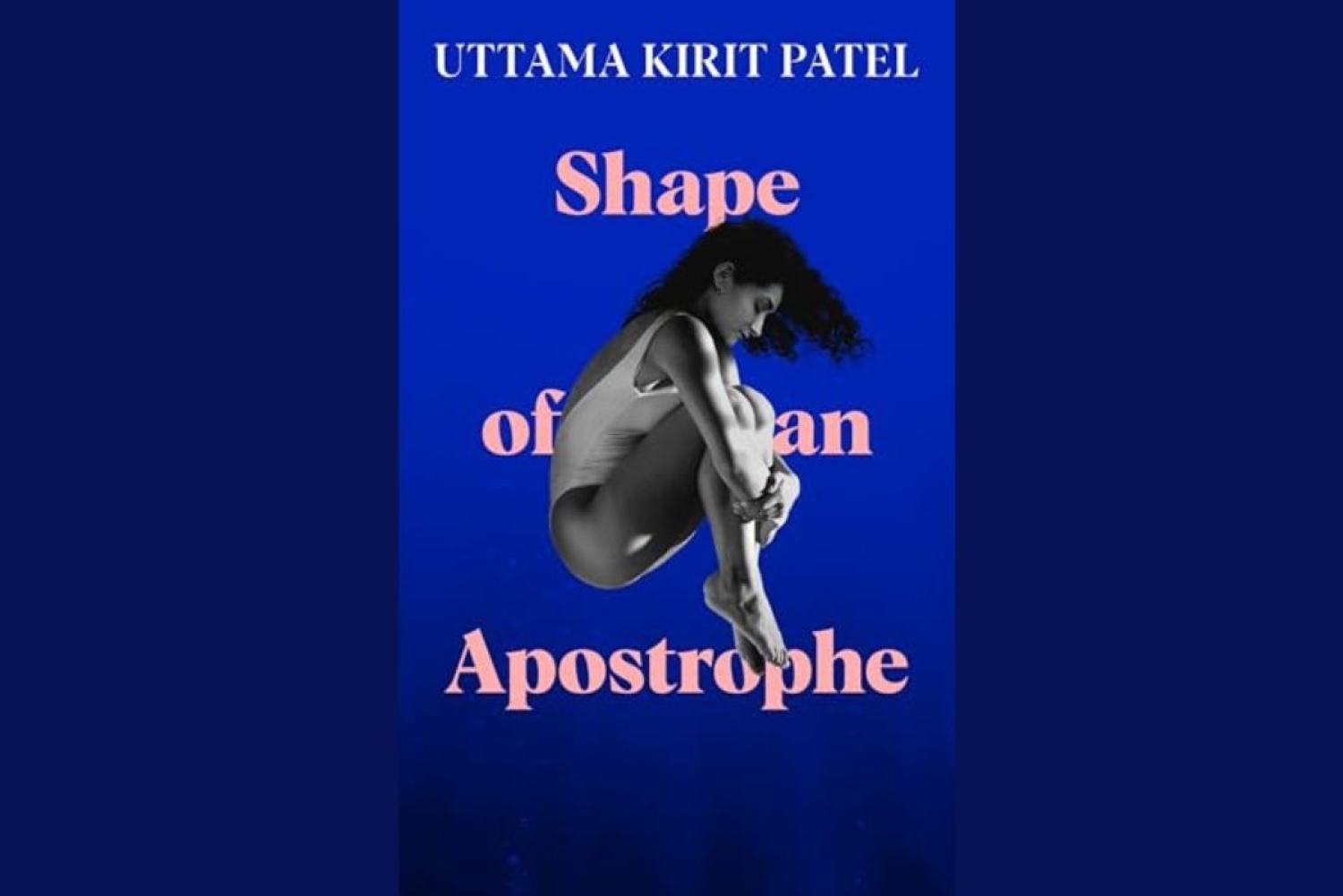

In her searing and intimate debut novel Shape of an Apostrophe (Serpent’s Tail), Uttama Kirit Patel delivers a profound meditation on motherhood, womanhood, and the choices that define us or undo us. Set against the shimmering backdrop of Dubai and deeply rooted in the domestic spaces we often overlook, the novel follows Lina, a woman who has never wanted to be a mother, as she navigates the emotional and existential terrain of an unexpected pregnancy.

Uttama, who has long been fascinated by the quiet revolutions that unfold within homes and hearts, crafts a narrative that is both deeply personal and fiercely political. With lyrical prose and arresting metaphors — particularly her recurring use of water and swimming — she explores themes of autonomy, guilt, rebellion, and the invisible labour of women.

We speak to Uttama as she dives into the heart of her novel — the intersection of guilt, resistance, and identity.

The Metaphor of Water

The water, swimming, and all that imagery primarily emerged as a way to give Lina a safe space. As she navigates her journey—through pregnancy, family, and everything else she’s confronting—water remains her one constant source of solace. I was drawn to the fluidity of water, the way it changes, and that sensation of weightlessness, which felt metaphorically resonant, especially as she experiences pregnancy. Water becomes a place of comfort and, perhaps, of belonging—something she’s struggling to find in other parts of her life.

The novel is set in Dubai, and Lina grew up in Abu Dhabi. So water, quite literally, surrounds her and is part of her landscape. I didn’t want to ignore that. It opens her up. It’s where she just is, without having to perform or explain.

Challenging the notion of Motherhood

What I really wanted to explore was the choice not to be a mother. It started with a letter I wrote to the biological child I chose not to have. Since I was 16, I’ve wanted to adopt. But after I got married and family started becoming a tangible possibility, I found myself overwhelmed— mostly with guilt. I realized I felt guilty for making an unconventional choice. That’s where Lina’s character comes from. Why do we feel guilty for choosing differently? I loved the challenge of writing someone unlike me. I’ve always wanted to be a mother, but I wanted to write a woman who never has.

Then, Lina does fall unexpectedly pregnant. So I wanted to ask: What happens when we’re forced into a role we didn’t want? How does it feel to be trapped inside other people’s expectations of how we should feel or behave? The assumption that all women want to be mothers is just not true. And when men don’t want to be fathers, there’s far less judgment. Women carry this additional burden—what do we owe to our families, partners, or to society simply because of our biology? That’s one of the things I wanted to interrogate.

“The assumption that all women want to be mothers is just not true. And when men don’t want to be fathers, there’s far less judgment. Women carry this additional burden—what do we owe to our families, partners, or society simply because of our biology?”

Setting the novel in a domestic place

I think the domestic space reflects wider societal shortcomings and offers a chance to change them. Most of the novel unfolds within the family, within the home, because that’s where so many gender dynamics play out subtly and persistently.

It’s in everyday things—who buys the birthday gift for parties? Which parent is in the school WhatsApp group? A father doing basic childcare is a ‘hands-on’ dad, but there’s no equivalent praise for mothers, who are held to higher standards.

There’s this quiet sexism in domestic roles that often goes unnoticed by men and is accepted by women as part of life’s everyday annoyances. I wanted to ask: Can we push back within our homes? Because that’s a space we have control over. And if we have children, do we want to pass down these gendered patterns?

Learnings from Writing

I have lived with these characters for seven years. Writing them has made me more forgiving, more open. You learn so much by exploring someone else’s motivations—especially when they’re different from your own. The core idea of the novel never changed. But over those seven years, I adopted my child, then experienced my fertility journey, including multiple miscarriages. Of course, that shaped how I wrote. I’ve learned a great deal from the characters.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

3.06.2025