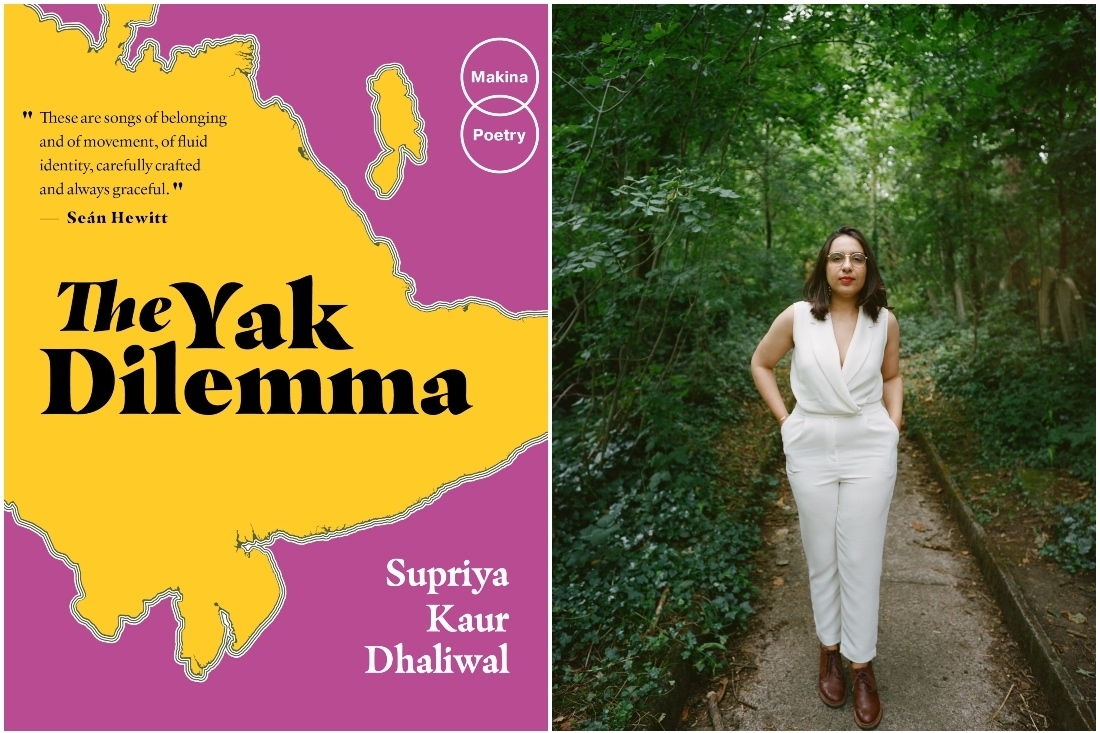

The months of April and May have proven to be some of the most cataclysmic months for India since the pandemic began. On a personal front, while I was down with Covid myself, my anxiety and anguish found little to no relief. As someone who has always found enlightenment and solace in travel, the fact that after facing the most traumatic event of my life, I cannot venture outside to placate the aftereffects, has been wearying. In a trying time like this, getting to read Supriya Kaur Dhaliwal’s The Yak Dilemma was a boon. Amidst the imposed stasis and languish, it allowed me to travel to places and within, through words and verse, like no other. The debut collection of poetry, that traverses terrains both known and unknown, is riveting. Notions of home become a pertinent concern as the poet indulges us in a poetic voyage, tinged with a beguiling charm. As we stumble across the lesser spaces our existence inhabits, the journey proves to be an illuminating exercise about the self and our surroundings.

In a conversation both insightful and emotional, Supriya tells us more about the inception of the book, the loss of her mother, poetry in the time of pandemic, and more.

What led you towards poetry?

I started engaging with poems at a fairly young age. Spending time with books was naturally comforting for me while growing up as an only child. Poetry was maybe just a medium that suited me the best. My first publication was in The Tribune’s now extinct column called Rhyme Time, which they ran for poems by students from schools and colleges across the country. I was 15. That turned out to be such an affirmation for me that it would lead the way for the rest of my life.

I think I have spent more years of my life consciously engaging with poetry than the years that I have spent away from it. At this point, it is almost as if I am tethered to it.

Which poets have influenced your oeuvre so far?

Anne Carson is my literary godmother. I am much indebted to the Irish poets who paved the way for my learning and understanding of the craft, mainly Ciaran Carson, Derek Mahon, Eavan Boland. Here in India, I am grateful to Tishani Doshi for entrusting poets like me with the belief that we could be real too. Reading Wislawa Szymborska is always like experiencing the entire ocean even when we are looking at a bucket. Over the last few years, I have been moved by the work of Zaffar Kunial, Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Solmaz Sharif and Rebecca Perry.

Are there any particular themes or concerns you find yourself gravitating towards with your poems?

Borders. Breaking free from the canon while also wanting to learn from the canon. Poems are to a poetry book what paintings are to a museum. I think about this a lot. How I approach different languages is an integral element of my creative practice. In this book, I stuck to the notion that every language for me is a foreign language.

What inspired The Yak Dilemma?

On the day of the first workshop of my Poetry MFA in Belfast, our entire cohort sat around a table and our lecturer brought in a poem that mentioned yaks. To my surprise, most people in the room were unfamiliar with what a yak really was. It was a funny moment. I was flabbergasted but as someone who grew up in the Himalayas, I also experienced culture shock in a way like never before. That is how it all started.

What would you say is at the core of the collection?

No man’s land. Visible Cities. Invisible Cities. Dreams of a sunrise at Hagia Sophia. Rooms with dictionaries for your favourite dialects.

Could you give us an insight into your creative and curation process behind the book?

I keep lists. That is how I am able to get through my poems, or even most of my life. Lists for metaphors, sentiments, sexy sentences, kind and unkind anecdotes thrown at me by strangers, poems I wish I had written, songs I wish I had sung and so on. When I have enough lists ready, I know I have a poem ready. I did not have a tough time selecting the final poems for the book. But putting them in four different sections and then arranging them in those sections was quite challenging. It was like I was throwing a map at the reader where the reader knew about their destination, but since all the joy is in the journey, it really was in my hands to decide what would the reader like to experience first, what would they like after that or what would keep them glued till the very end. When I printed my draft, I laid all my poems on their back on the floor. A lot of poets tend to do this exercise. A hawk’s eye is often a good judge when it comes to the curation of poems in a book.

The theme of home seems to be a major recurring theme throughout the collection. However, was a there a singular driving force, thematically, behind the making of the book?

I was definitely thinking a lot about homes while writing these poems. Houses of famous writers and artists were on my mind a lot. I was kind of obsessed with the idea of them. There was not a singular driving force, thematically, no. The book is rather an accumulation of multiple driving forces — no man’s land, home(s), roses, houses of writers and artists who moved me in different ways, rooms, languages, mobility, marigolds, shoes, kesar and so on.

What kind of challenges came your way as you endeavoured towards making and releasing your debut collection?

I signed the contract with Makina Books when the pandemic was a new alien reality in our lives. I was living in London at the moment and we were on the brink of everything starting to go astray. Robin, my publisher, and I first planned for a late summer release in 2020. Late summer turned to autumn, and then autumn translated into winter. Our original timeline of events might have gotten pushed further as the year went on and the world did not seem to come back in order, but our project evolved so much over this duration. So, it all worked out in the end. Even if the book is out in the world in so many bookshops in its full glory, we (all the makers and the well-wishers of the book) have not all yet had a chance to raise a toast to its birth. There have been no launches, no readings thus far. There has been no way to engage with the readers of this book in person in any way. All that there is exists behind our computer screens and nowhere beyond.

We have very exciting plans for the future, and we are very positive that all our plans will be properly executed once we get a positive sign from the universe. We are planning a reading by the beach in Whitstable, Kent. The audio book and the e-book for The Yak Dilemma are on their way. When I started to write this book, I had my Mum by my side — my Mum, who vouched for me when I was a stubborn teenager writing poems that rhymed so poorly on the back of my school notebooks, my Mum who was always so certain that it will work out so well for me, my Mum who was the most radiant woman on my graduation day in Belfast, my Mum who made me believe that all that there is in this world could be a poem. My Mum was by my side when we were still in the process of choosing the perfect colours for the cover of The Yak Dilemma. But because life took an evil turn after that, my Mum was not with me when The Yak Dilemma was birthed. She did not live enough to hold a finished copy in her hands. It is hard to realise if there is any purpose to this life at all when we are grieving. All these months I have spent grieving, I have struggled to compose an email, let alone finish the proceedings to bring an entire book out into the world. I do not know how it all happened. Maybe it happened only because my Mum wanted for it to happen.

What do you hope the readers take away from this book?

Ever since I started reading, I have loved the moment I entrust all my good faith in the text, all my happiness, all my sadness, all my freedom in its many moods. I am happy that the book is being perceived as an agent with which the readers can cross so many borders on the page and in their imagination while we sit locked down in our homes. I did not think of this when I was writing the book because we could still travel wherever we wanted without labelling it as an extremely serious health hazard. Yes, my goal might have been to outline an uprooted existence that troubles the very notion of home. Here I only hope that the readers travel with me and try to fathom the anxieties that float in the expanses between so many places we choose to call home.

In a time like ours, what role do you think poetry plays or can play?

I spend a lot more time with poetry than anything or anyone else in this world. And I do get this a lot at different walks of life that I unnecessarily attach too much value to poetry. I do not feel guilty about that. I will quote Adam Zagajewski here to do the rest of the talking, ‘(…) poetry is mysticism for beginners. That German tourist traveling through Tuscany with his funny little book helped me to realise that poetry differs from religion in essential ways, that poetry stops at a certain moment, stifles its exaltation, doesn’t enter the monastery, it remains in the world, among the swallows and the tourists, among palpable, visible things. It describes people and things, participates in their concrete existence, walks streets wet with rain, listens to the radio, goes swimming in Mediterranean inlets. It’s a little like those politicians who like to remind us how close they are to ordinary life, they know the price of butter, bread, and bus tickets; and like those politicians, poetry can be less than truthful, since it yearns at times for something different.’

Lastly, how have you been coping with the pandemic and what are you working on next?

At this point, I do not think I am coping with the pandemic well at all. Everything feels like a challenge. Everything is a challenge — trying to stay alive, trying to keep our loved ones safe and alive. Here in India, we are in the worst position possible. Normal life feels so far away that I have even stopped thinking that anything will be normal ever again. I was this year’s Charles Wallace India Trust Fellow at the University of Kent, where I started to develop a sequence of poems loosely based on the life of the Irish theatre practitioner Norah Richards who lived here in Andretta, Himachal Pradesh. There is a poem called ‘Appointment with Norah Richards’ in The Yak Dilemma that touches upon that. The Norah Richards in my poems comes alive in a contemporary setting — she drinks coffee with Annie Besant, goes to the Farmers’ Protest at Tikri Border, brings mulberries to Andretta from Wular Lake. I am very excited about the different forms that this project is taking. A lot of it also feels like reconnecting with something that I lost long ago. I think I am tracing the granularity of belonging yet again.

The book is available for purchase here.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 26-05-2021