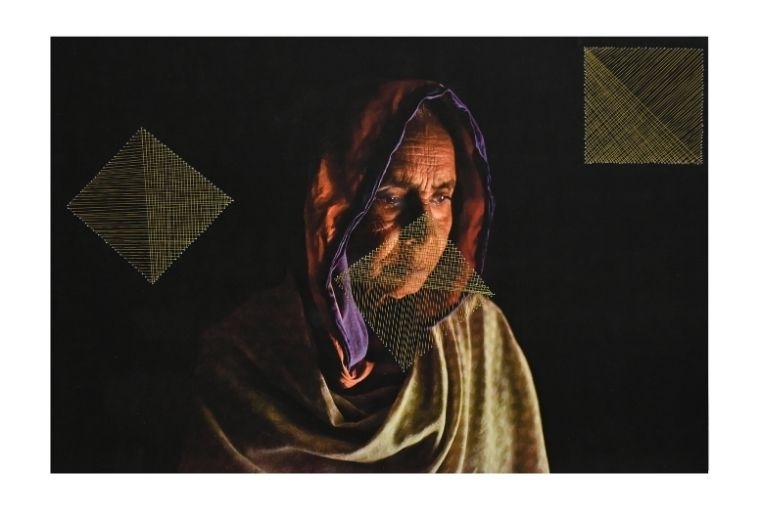

Behula these Days C-type print on archival paper and golden silk thread 12.5 x 18.75 in 2025 Edition of 5 + 2AP

Behula these Days C-type print on archival paper and golden silk thread 12.5 x 18.75 in 2025 Edition of 5 + 2AP

Bangladeshi artist Ashfika Rahman, who is the winner of the Future Generation Art Prize, presented by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation in Ukraine in 2024 voyages between art and documentary in her expressive multi-media practice, in an effort to archive the socio-political issues faced by the marginalized and indigenous communities of Bangladesh.

On-view at Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi, and Titled Of Land, River, and Body (Mati, Nodi, Deho), her show marks the artist’s first-ever exhibition in India to which Rahman brings an ambitious and immersive body of works from three ongoing series: Than Para; Files of the Disappeared; and Behula These Days. The exhibition features three large-scale installations along with a series of photographs, as well as interactive audio–visual elements. We spoke to her about the process behind her art.

You work across many different artistic mediums like textile, photography, and installation. Through your experience, how does the choice of medium change the way a story is told or felt for you as the creator?

This is a very interesting question to address, to be very honest, something most people are curious about because they have an impression about photography or the 2D medium. But I think this question about medium nowadays needs to be rethought. Should I still, or should we still think about medium? In the era of AI, when you actually can do many things with AI, I think we are entering into an era where we can actually see or we can only move as a human being with our intellectuality and thoughts. So, the medium probably will not be a main concern. Of course, there will be room for craftsmanship, but we probably need to survive with our ideas and political understanding and thoughts, in the era of AI.

Photography probably is not only a way to record, there will be many more ways to record. I will do what I do, but I have to see things differently. I have to see more ways to record the truth at the same time. I discovered that installation is also a medium. For example, if you see the installation in the exhibition, the fingerprints are actually a document, a documentation of real people. But today, it’s not photography, but still it’s recording the truth. I don’t look for a medium, but I look for the context. What are the contexts and what can actually connect the context more closely? For example, for this one, we needed the metal brass that is metaphorically presenting the calling of God. But then other work, probably textile, because textile is more close to women and how they actually express themselves.

Than Para (No Land Without Us) 838 temple bell (brass), golden silk threads and metal frame 48 x 48 x 78 in 2025

If you could take us back to the beginning, how did this body of work come about, and how does it tie into your broader practice of documenting land, river, and body?

In this particular show, we have three different bodies of work that we very sensitively selected. In my practice, I’m deeply influenced by my mother. She was a social worker and had been working in different parts of the country, especially in the more rural parts of the country. She had been supporting mostly minor communities, indigenous communities. Her practice was more or less about violence and suppression. She is a single mother. My father died when I was one year old. So I have been travelling with her all my life. I am revisiting all the places that my mother worked.

All my works are actually places that my mother has worked on before, or the issues that my mother addressed at one point during her period of working. I’m meeting all these people and trying to collaborate with all the communities that she worked with.

It’s more or less like I’m re-archiving the facts, or issues, or suppression, and some history of suppression that has been going on since my childhood. Nothing has changed. It’s even more pressing now. I’m not an activist or social worker like my mom, but I address it as an archivism. I’m archiving things for the future and also trying to put together all these stories as a dialogue.

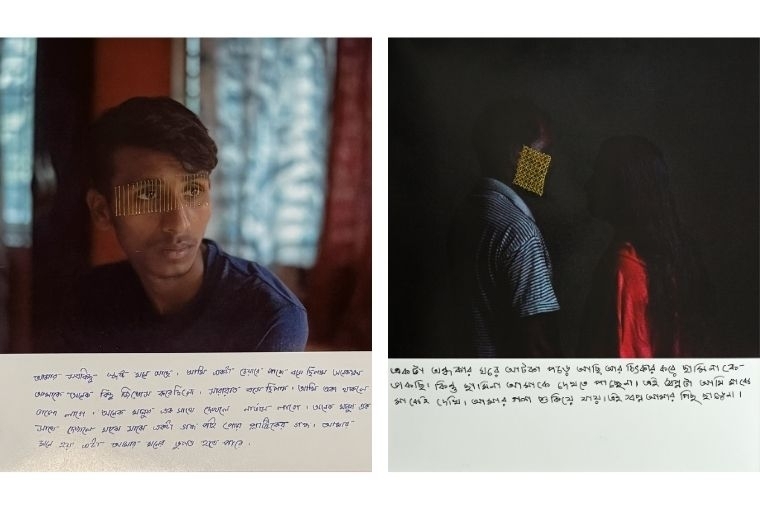

Than Para C-type print on archival paper and golden silk thread 12.5 x 18.75 in 2025 Edition of 5 + 2AP

How do the themes of land, violence, and displacement come together in the exhibition?

My early work was very political, where I was working on violence against indigenous women in the Chittagong hill tracks area. While I was working on that issue, I realised that it’s not really an individual incident. Rape has been used as a war weapon systematically by the state and it comes with cultural colonisation, land grabbing and so many other issues. One of the series is about land grabbing. This work talks about a village where people have been living there for 100 or 200 years, and they have no documents. The state is forcing them to move because they want to make a tourist village or an industry there.

This has been going on for many years. Many villages can’t claim land back because they don’t have a document, when it comes to fingerprints. If you have a fingerprint, then you can claim the land. If you don’t have the fingerprints on the document, then you cannot claim the land. No fingerprints, no land. We are talking about women around the river who have been suffering from gender based violence or climate based violence. It is about displacement. It is about disappearance. It is also about silence. The land became the witness, the river became the storyteller and the body became a form of silence.

Behula these Days C-type print on archival paper and golden silk thread 12.5 x 18.75 in 2025 Edition of 5 + 2AP

How does using folklore, myths, and local forms of expression allow you to tell these stories differently from official records?

The aesthetic gives me a veil to tell the same story, record the same story, which is not possible through mainstream media. It gives me freedom and power to reach globally. Each work is a local story but has global access. It is open-ended. Anyone can reflect on the work. I try to understand the local language, what is the language people actually use to tell their story.

In Bangladesh, women are very shy and not expressive. They never say I love you. They express themselves through stitching on tablecloths, pillow covers, handkerchiefs. They write one line with flowers, birds, maybe a line of poetry. They never say it. This is their language. This is how they communicate. I wanted to use their own language to express their own story rather than putting a contemporary medium on them. That is why the Behula installation uses Bangla, Tripura, Marma, Chakma. This is their language. I could have done an English translation, but that is not their language. I am a medium to transform their language and story into a contemporary framework. They did their part and I did the installation. We worked together in collaboration.

How did you hold space for your own vulnerability while working on such deeply personal histories?

I have lived a very complex, complicated life. I was raised by a single mother who was a social worker. I think I reflect on my own struggle through my work. I see myself through this. I never had a home. I moved from one place to another. That feeling of displacement is embedded within me.

We were an all women family in a Muslim country and we were not always welcomed. We had to move from one society to another. When I talk to these people, I can feel their displacement. Many stories in Behula are also my own story in a different form. It is my way of revisiting my own experience through work.

L: Files of the Disappeared Case - 14 Print of archival paper & golden silk thread with lightbox 13 x 12.25 x 3.25 in 2020 Edition of 2/3 R: Files of the Disappeared Case - 1 Print of archival paper &

Has anything from the audience response to the exhibition stayed with you, and what are you working on next?

My only hope was that people would look at it critically and ask questions. I received immense curiosity. People asked questions. That was the purpose of my work. That is why it felt successful to me. Apart from that, I am continuing my residency at Rice Academy in Amsterdam and working on new things.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 14.1.2026