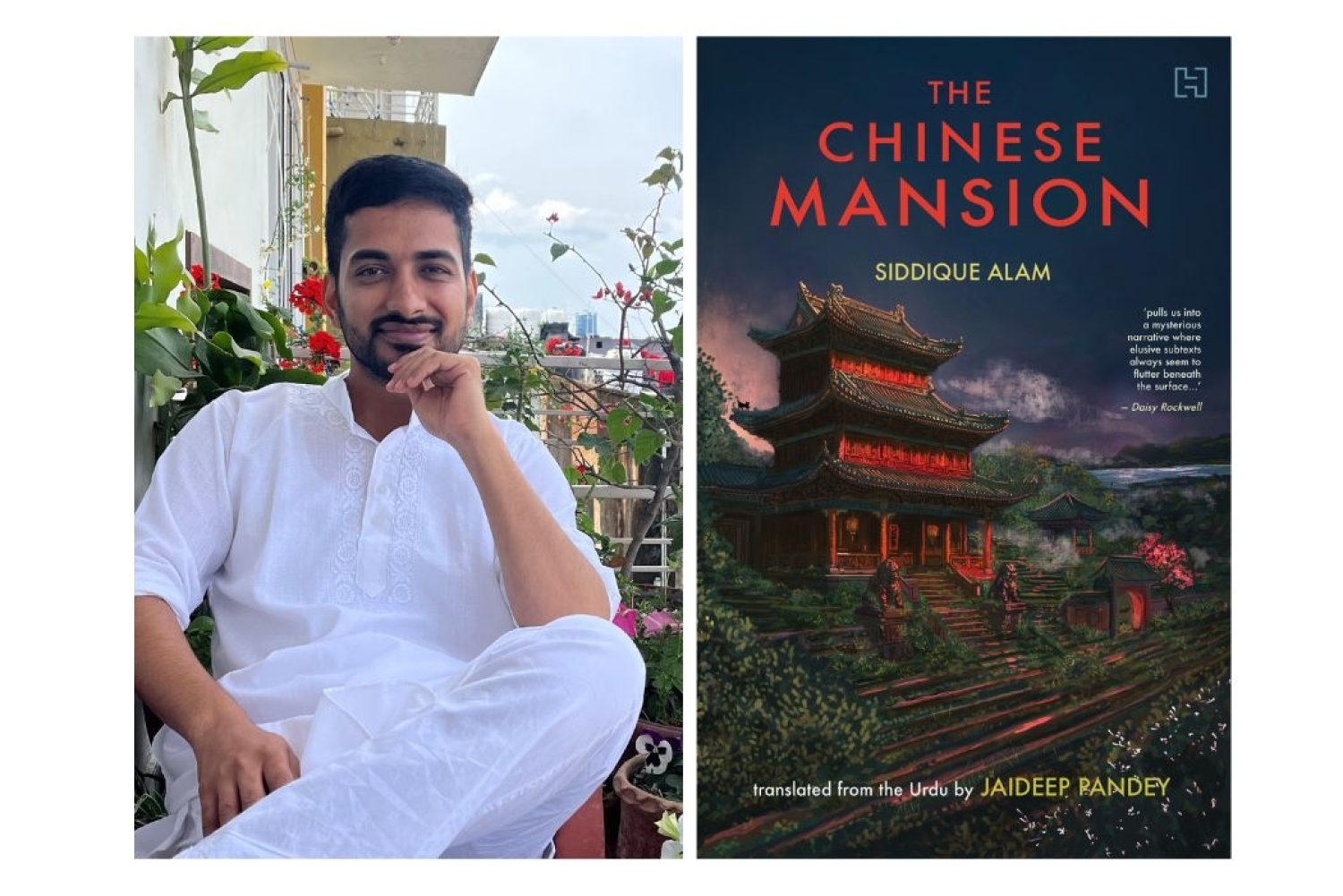

In The Chinese Mansion, language operates like a quiet spell; subtle, almost transparent, yet deeply unsettling. As the story unfolds, what first appears to be placid, descriptive prose gradually reveals layers of surrealism, psychological unrest, and haunting traces of trauma. Translating such a novel, a work that hinges on what remains unsaid as much as what is told, is no small task. Jaideep Pandey speaks to us about the process of carrying this multi-layered world into English.

The Journey

My journey with translation began unconsciously during my undergrad in English Literature, which in the Indian context, always reverberates with a myriad of translational voices. As time went by, I was exposed to more expansive definitions of translation, as not just moving between languages but also media, interpretational strategies, and genres. As a graduate student in Comparative Literature, I have had to move between English, Urdu, Hindi, Persian, and Arabic for my research. In the beginning, I thought of it as a means to an end— i.e. to bring together archives for an English readership. However, I have slowly begun to see translation as fundamental to my experience of reading, as it allows me to immerse myself in a text emotionally to an extent that dry, critical analysis cannot.

The Story

I think there is a real dearth of English translations from Urdu outside North India, overlooking Urdu’s robust cosmopolitan presence across several regional geographies of the Indian subcontinent. Siddique Alam’s work engages with a distinctly Bengali landscape, whether rural or urban, and I wanted to share one among many such examples with my fellow English readers. Additionally, I feel that Urdu is often subjected to unfair ethnographic expectations to “document” Muslim lives, which paradoxically further contributes to its minoritization in India. While it is a living document of a thriving yet marginalized Muslim culture in India, it also does so much more, and The Chinese Mansion is a great example of Urdu’s long history of masterfully playing with form, genres, and styles of literary fiction.

Challenges

The biggest challenge for me in translating The Chinese Mansion was to convey this while maintaining the subtlety of language. Alam, for example, uses long, descriptive sentences or a present continuous tense to pull the reader in. These are features which have literary precedents in Urdu but were hard to communicate in English in a way that both ensured a smooth reading experience yet unsettled the reader, as the original does.

“Even as the translator holds power over the source text in how they choose to translate, they must first submit and surrender to the language and think intimately with its nuances on its own terms. ”

Translation Choices

I study circulations of literary styles, registers, and genres across Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia, to try and move beyond what texts are considered local versus cosmopolitan. I also attempt to reorient these networks of circulation from the vantage point of the Global South. Alam is one such author, and his writing is influenced by Urdu writers such as Naiyer Masud, Shamsur Rahman Farooqi, Khalid Jawed, but also non-Urdu writers such as Anton Chekhov, Derek Walcott, Rudyard Kipling, Franz Kafka, Milan Kundera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, among several others. Translating Alam’s novel allowed me to explore my academic research in a more immediate and visceral sense. In my translation of The Chinese Mansion, I have tried to preserve this dual scale of Alam’s literary world, which is both deeply local and tied to Indian landscapes, but also grounded in global avant-garde and magical realist fiction, which it molds to speak to South Asian realities.

Language

As I began translating from Urdu, I slowly began to question my own patronizing attitude towards the language. I think this has something to do with the role of the non-native translator. Even as the translator holds power over the source text in how they choose to translate, they must first submit and surrender to the language and think intimately with its nuances on its own terms. I think this phase of surrendering has the power to humble the non-native translator and trigger a process of unlearning their prejudices.

The Future

I am currently translating another short story by Siddique Alam, which is an existential tale set in the urban jungle of Kolkata. I am also co-editing a special issue of translations from the Muslim World with a colleague of mine at the University of Michigan, which includes Indian languages like Punjabi, Urdu, Assamese, and Malayalam (alongside Persian, Amazigh, Dari, Turkish, Arabic, and Armenian). It will be out in December 2025.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 25-8-2025