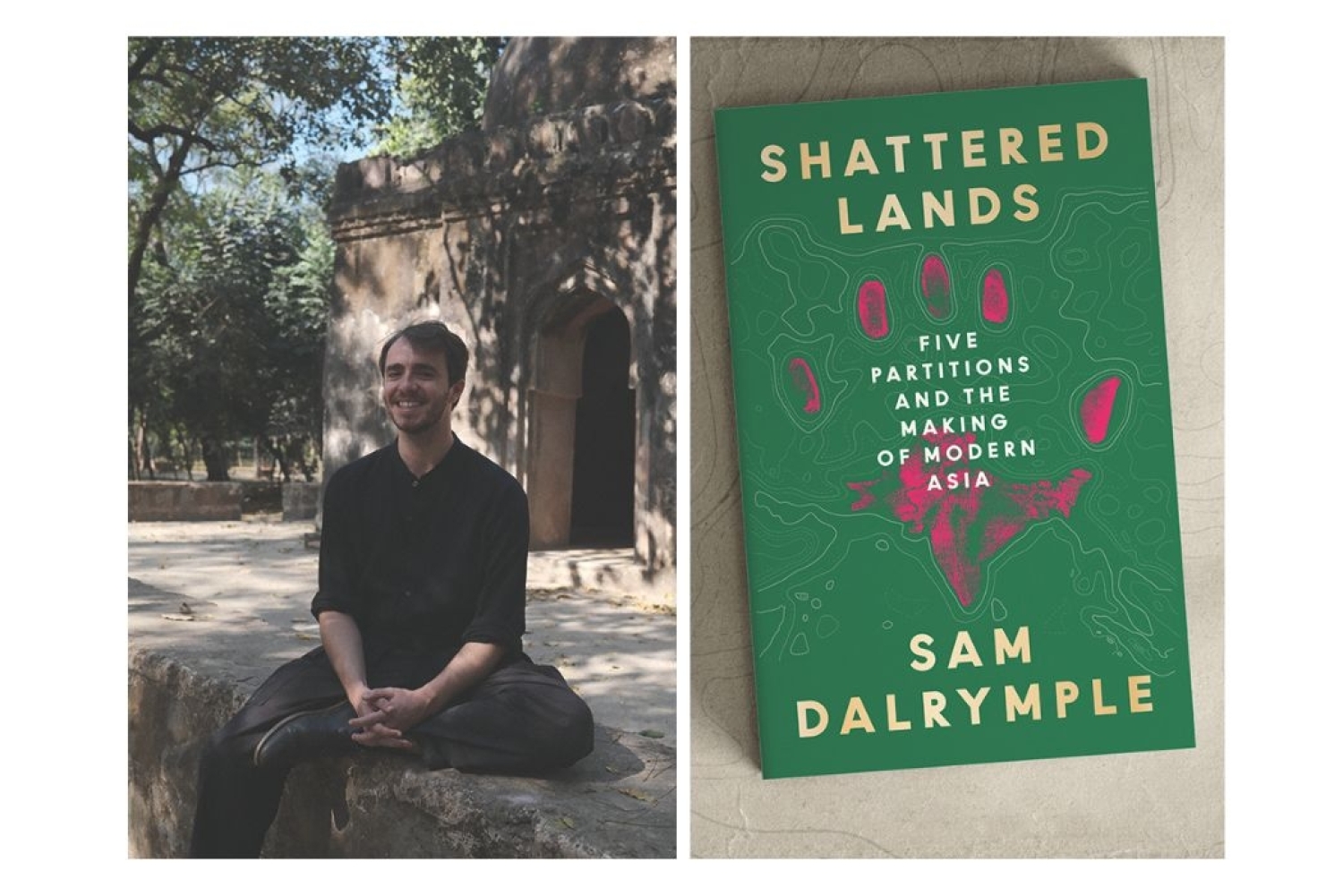

It’s no surprise that Sam Dalrymple has ventured into writing a history book. As the co-founder of Project Dastaan and the author of numerous columns on the hidden architecture of this country, many have been eagerly anticipating his debut. Following in the footsteps of his father, the renowned historian William Dalrymple, Sam's book Shattered Lands: The Five Partitions of India, 1937-71, released this June. The book offers a much-needed narrative on one of the most significant histories of the Indian subcontinent and on the various group of people who were once officially Indians.

We sit down with Sam to get a sneak peek at the fresh perspectives he brings to the conversation on Partition, as well as the origin of his personal interest in the subject.

You always wanted to study physics, tell me how you re-routed the path to becoming a historian.

As a kid, I spent a lot of my childhood being dragged around by my parents to all sorts of places in South Asia—random courts in Rajasthan, Bengal, and family holidays off to Bamiyan in Afghanistan. But I was convinced that I was going to study Quantum Physics and I got very invested in all of those Stephen Hawking-type questions about the nature of time. I loved Doctor Who as well.

There was this one family holiday to Afghanistan, where suddenly I was blown away. It was this world that I could recognise because it felt so similar to Delhi, but it was also so different. There were all sorts of things that just fascinated me that I’d never conceived of. All these stories about Alexander the Great having passed through here or the story of Bamiyan Buddhas and I didn’t even know that Buddhism was practiced here. There was a city opposite called the City of Screams, which had been sacked by Genghis Khan. It was just all of these kinds of bits of history that I’d never associated with each other, coming together in this fascinating, beautiful country, which was quite different from how it looked in 2014, when the Americans were still there. For example, there were ski resorts and Japanese restaurants and all this kind of stuff that I hadn’t associated with Afghanistan. It was just before everything began to collapse, and the Taliban came into power.

I started teaching myself Persian. Then, I didn’t get into my dream university for Physics, so I enrolled in a language course, using the money I’d earned from working in a bookshop. The rest is history. Suddenly, I got an internship in Persian, studied at university and here I am in a very different career.

At what point got you interested in the history of Partition specifically?

I was studying Sanskrit and Persian. I was much more focussed on the medieval world or more around Afghanistan, and Partition was quite peripheral to me for all of those years. Until my friend Sparsh came up with this thing called Project Dastaan at university. My other friend Ameena could visit Sparsh’s ancestral home and Sparsh could visit Ameena’s ancestral home. Sparsh’s family had gone from Pakistan to India and Ameena’s had gone from India to Pakistan and yet they couldn’t visit each other’s homes. Initially, it was just to try and bring back one or two families using virtual reality. It was quite a small-scale project. Through this project, gradually almost all of my childhood friends and early acquaintances started opening up about their own Partition stories.

Then, I think most surprisingly, my grandfather passed away and I realised that he had a Partition story. He had been brought into the army during World War II as an eighteen year old. We’d always wondered why he’d always refused to come visit us. It was only the day before his funeral that we were flicking through his old war diaries and war scrapbook and it began to make sense why this man might not have wanted to come out to Delhi again.

Partition is the largest migration in human history and it’s the only border in the world where it’s impossible for anyone who migrated, to revisit the homes that they came from and visit their old friends.

“Partition is the largest migration in human history and it’s the only border in the world where it’s impossible for anyone who migrated, to revisit the homes that they came from and visit their old friends. ”

There are a vast number of books on Partition, from Urvashi Butalia to Aanchal Malhotra, each delving into the different nuances of this pivotal historical event. So, what new perspectives does Shattered Lands offer?

Shattered Lands came from a conversation I had with someone from Tripura when we were trying to expand our understanding of Partition stories and not just focus on Punjabis and Bengalis but try to have a more representative scan of how Partition affected the subcontinent. Tripura is arguably the most demographically changed state in India by Partition and yet it never gets mentioned. It went from the majority Tipra or various Adivasi groups states to now a majority Bengali state as a result of the migration of Bengali Hindus trying to flee Bangladesh. I remember having this chat with someone and they told me that the northeast had three partitions. First, the separation of Burma in 1937, which cut off Arakan and Rangoon from India and divided the Nagas and Mizos. Half of all Nagas live in Burma; a third of all Mizos live in Burma. The Rohingya are cousins of Bengalis who’ve been stuck on that side when the border was drawn, then you’ve got ‘47 and then you’ve got ‘71 with Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan.

I think because Burma very rarely features in our idea of undivided India, I began to look at what India actually looked like in the 1920s. This India was far larger than we remember and stretched as far east as Burma but as far west as Aden in what’s now, Yemen. The princely states attached in the 1920s included places like Dubai, Abu Dhabi, bits of Yemen, Nepal and Bhutan. Just over just forty years, between 1931-1971, there are five ruptures that carve up this land into these twelve nation-states. So, Jaipur joins India, Bahawalpur joins Pakistan and then states like Kashmir get stuck in the middle. Literally, just nine months earlier, Dubai and Abu Dhabi had been part of that list but the Persian Gulf residency had been separated off and given to white people, because they were not perceived as Indian enough. This is a story that hasn’t really been told.

One of the most interesting stories from the Gulf, I had, was the origin story behind one family who are Hindu Sheikhs in the Gulf. There’s a Hindu Sheikh of Oman called the Khimji family, who are remnants of the Bania tribe. They’re remnants of this moment when Oman was essentially tied to Delhi and governed by the Viceroy. The five partitions is trying to expand the story to all of the borders that cut up—not the external borders like India’s border with China, but the borders that ruptured within people who were once at least, with official documents, Indians.

“Just over just forty years, between 1931-1971, there are five ruptures that carve up this land into these twelve nation-states... This is a story that hasn’t really been told.”

You’ve spent the last five years researching Shattered Lands. What was the research process like, and how did you approach gathering information over such a long period of time?

The book has interviews in eight different languages—English, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali, Konyak—one of the many languages of Nagaland that is spoken along the India-Burma border, Burmese and Arabic. Then, I’ve been to various private archives in Pakistan, the National Archives in India and various archives all across the UK. And I was just in Yangon in Myanmar, recently. I didn’t manage to get into the archives there but I got a lot of interviews. I’ve visited India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Dubai, Oman for the research in this book. I’ve tried several times to get to Yemen but Yemen proved elusive with the civil war going on.

Now, I like to think of it as a mix of archival and oral histories. I think the aim is to try to contextualise some of these oral histories. Rather than just having something that uses official narratives or oral histories to question these things, I’m trying to merge the two into a narrative.

This conversation is a part of our latest Bookazine. For more such stories, buy a copy here.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Photography Akshay Kapoor

Date 23-8-2025