Photo: Chloe Aftel

Photo: Chloe Aftel

As the announcement of this year’s Man Booker Prize winner inches closer, we revisit our conversation with one of the most lauded previous winners of the prize.

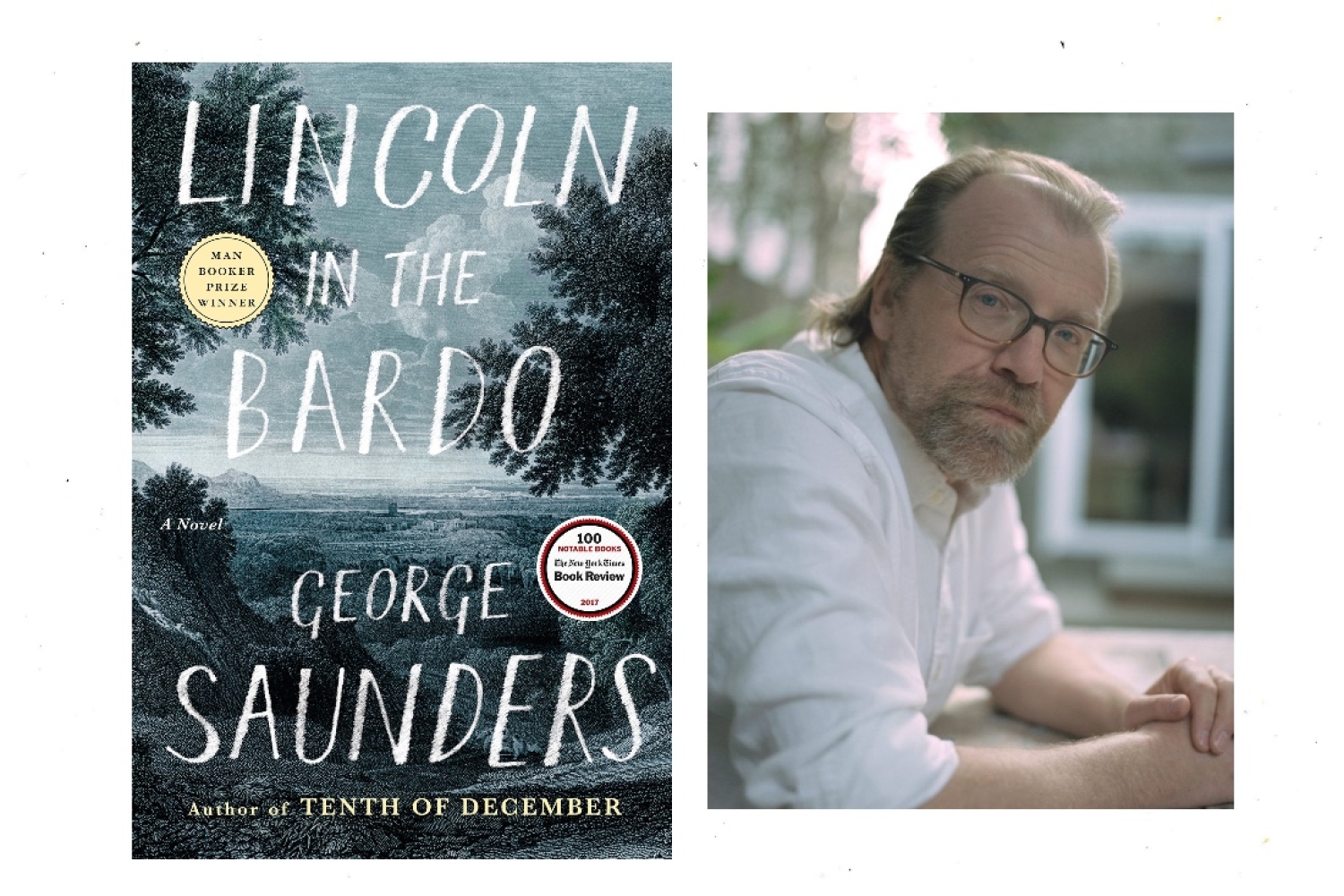

‘I had really decided that I didn’t care to ever write a novel,’ starts one of the world’s most beloved short story writers, George Saunders, who is this year's Man Booker Prize winner. ‘But I did want to write this one, if you see what I mean—I wanted to do justice to this material. As I was writing this book, I kept saying to myself: “Keep it short, let it become a short story if it wants to be one.” So the book seemed to operate on the same principles as my stories do, but maybe on a larger frame. I’ve been joking that it was as if I’d been building small custom yurts all my life, and someone commissioned me to build a mansion. The solution: build a series of linked yurts.’

That is the story of one of the most beautiful titles that the beginning of 2017 presented—Lincoln in The Bardo—with a narrative style as experimentally in-between as the bardo is, between life and death. A place of grief that Abraham Lincoln dwells in on losing his son Willie. In an insightful interview, Saunders reflects on his writing, art as the cumulative outcome of our many selves, and dealing with a post-fame debut novel.

What is your first memory of Writing?

When I was about eight years old I wrote a story for school, in which I time-travelled back to 1941 and joined the U.S. Army and fought the Germans, even though I was still eight years old. Not a masterpiece. It ended with this immortal and bloodthirsty line: “He had killed an amazing forty Germans!” A nun gave me a copy of Johnny Tremaine by Esther Forbes a few years later, and I was very taken by the style of that book. I remember walking around for weeks afterward, describing things in the tight, compressed voice of the book. 'Two nuns on pale sidewalk chat.'

Looking back on your journey, how would you sum up all the years of your writing practice? How has your craft evolved over the years?

I think my confidence and craft has expanded to allow me more direct access to the way I truly feel about things, especially the more positive valences—the times when life goes well, people are good, love wins, etc. Positivity of this kind is somehow technically harder to depict than dysfunction or violence [or at least it is for me]. I think I’ve also learned to look at a 'bad' character and enter into his or her mindset less judgmentally—which is good practice for living. Revising prose to make it more lively and kind and precise can be a way of 'practicing' being a loving person—writing slows down time, in a sense, gives us additional opportunities to get things right. In the real world, at time’s actual pace, it’s sometimes hard to be kind and present.

What inspired you to write Lincoln in the Bardo? What made you pick this story?

It was an anecdote I heard twenty years ago: Lincoln’s beloved son, Willie, died at eleven years old, in 1862 and, supposedly, Lincoln was so grief-stricken that he snuck into the crypt on several occasions to hold the body. I found that idea so moving and mysterious, and over the years it kept coming back to me at odd moments—and in particular that image, of Lincoln on a dark February night, in the middle of the Civil War, sitting there in the dark tomb with his son’s lifeless body across his lap. I resisted and resisted—wasn’t sure I had the technical skills to do the material justice—but finally said to myself something like, 'Well, you’re fifty-five years old—if not now, when?' In other words, I decided to err in the direction of possible catastrophe, just so I didn’t atrophy as an artist.

What does a father-child relationship mean to you?

I have two daughters, so for me the story was about that keen parental love—the love that takes over your life and gives you something to live for and shapes all of your decisions. One of the things Lincoln thinks in this book, as he’s trying to come to grips with his loss, is: 'Love, love, I know what you are.' In other words, he can say with complete certainty that whatever love is, he has experienced it. That is certainly true of my relationships with our daughters. There is something wonderful about that pure, selfless love we feel for our children. But then there is that terrible contradiction that we all labour under: we love, and yet whatever we love [a person, a place, a time, an idea of ourselves] is absolutely conditional and bound to change. How do we make sense of this? How do we live joyfully in the face of this?

Was it considerably more time-taking and challenging, in terms of patience and research, for you to write this novel?

Not really, to be honest. When I write stories, I spend a lot of time figuring out the events, and that usually involves a lot of obsessive re-writing and then throwing stuff away—I discover plot by revising, and that is very time-consuming. Here, at least I knew the basic outline of the events [Lincoln comes to crypt, holds body, leaves]. It still was a slow, laborious process but the time was spent more in finding the best transitions and trying to make beautiful juxtapositions and writing just the right speeches, than discovering what happened next. There was a lot of research but I would do that at night, or when I didn’t feel like writing new text. Mostly I loved the feeling of being totally inside of this world for four years. That led to a lot of new artistic feelings—happy surprises, plot developments that threw off sudden and unexpected light…

High expectations cause much pressure…did that affect you in the course of writing?

No, because I was pretty sure, for the first year, that I’d end up throwing the project away. So that let me be a little reckless and wild. And I’ve learned a certain mindset from all those years of writing stories; it’s difficult to describe but it has the feeling of turning to anything and everything that might impede my artistic freedom [self-consciousness, caution, fear, a too-controlling mind] and saying, basically: 'Get thee behind me.' I don’t like to fail and don’t want to fail and don’t find it interesting to fail.

Also, there was one moment, early on, where I found myself feeling a little scared, and thought to myself: 'Come on, man, you’ve had a good run as a writer. If you dropped dead right now, and given where you started from, you’ve done pretty well. So just go for it.' That was liberating and had the effect of dissolving any self-imposed pressure.

Can you take me behind your creative process as it occurs?

It’s very intuitive and iterative. I basically just start reading the section at hand and trying to react to it spontaneously. If it’s giving me pleasure, good. If not, I want to know why not, and am okay with the idea that the answer may not be completely articulable. [That is, I don’t care about naming what’s wrong, or conceptualising about it—I just want to fix it.] So a part might just feel slow, or a phrase seems to need tightening, or something is not making logical sense. And the fixes are occurring in the language, at the line level, through revising. So I am editing, then putting in those changes, re-reading, editing, re-entering those changes…over and over, until I feel my judgment waning because I’m getting tired. Then I’ll go do some research or reading. But over the course of many years, this process gradually creates something more complex than you could have imagined, that is firing at a lot of different levels—it’s smarter than its writer, so to speak.

One interesting anecdote from the birthing of this book that you’d like to take us behind.

In the book, I’ve presented some actual historical texts, rearranging these into a sort of master narrative of certain real historical events. Sometimes this meant typing up dozens of pages of other peoples’ writing, then cutting these blocks of text up with scissors, and arranging them on the floor. So 'writing' meant: me, on my hands and knees, darting around the floor like a mantis, moving slips of paper around. For awhile I started to feel a little insane—like I was wasting my time, was not 'really' writing. But then one day I had a finished section and couldn’t help noticing that it was better than the first version I’d put together and that it was doing important emotional work in telling the reader who this little dead boy had been in life. So then I thought: 'All right, then, being a novelist might involve some legitimate curatorial work.'

The biggest learning you took away from Lincoln…

I think it was simply that art proceeds mysteriously, in linear proportion to hard work and immersion. I never in a million years could have planned or foreseen the final result when I started out, and that result came from tens of thousands of small decisions. I find that notion really lovely and encouraging: art, as the cumulative outcome of the many selves you are as you work on it, over many years, an outcome that is, somehow, better in its totality than you are as a person at any given moment– kinder, cooler, more emotionally alive, more comfortable with ambiguity, more loving, more complex. So, seen this way, art is a way of forging a model of our best selves, over time.

Who are the new writers that you see as promising?

Some new writers I’m watching are: Emma Cline, Mariana Enriquez, Will Mackin, Camille Bordas, Danny Margariel. One of my favorite younger writers is Rahul Mehta, a former student of mine who has a new novel coming out soon. The essayists Maggie Nelson and Ta-Nahesi Coates are very important and brilliant voices. I will read anything by Zadie Smith, Miranda July, Dave Eggers, Jeff Eugenides, Tobias Wolff. My wife, Paula Saunders, just finished and sold a beautiful first novel called The Distance Home.

What is next?

Good question, that seems to have come directly from my conscience. I really don’t know. I have an empty desk for the first time in many years. I am working on a TV show with Amazon, and have a few ideas for essays. But really, I’m waiting for the 'fiction well' to fill up again. In the immediate future, I have a big tour of the U.S. to promote this novel, and I’m looking forward to that. It’s always fun to be out in the world, seeing how things actually are, talking to people, etc. That is really the best way to get that well to fill. And, of course, we are all wondering what’s going to happen here politically after a crazy and disturbing [for many of us, anyway] election. It was interesting to finish writing about Lincoln and then jump right into this political season. It’s clear that the issues that were at play during our Civil War never got addressed, and continue to haunt us—issues of race and equality, and the way America has never yet fully lived into the beautiful idea stated in the Constitution, that all beings are created equal. So…an exciting time to be living and thinking and writing.

Our conversation with George Saunders was first published in our Design Issue of 2017.

Text Soumya Mukerji