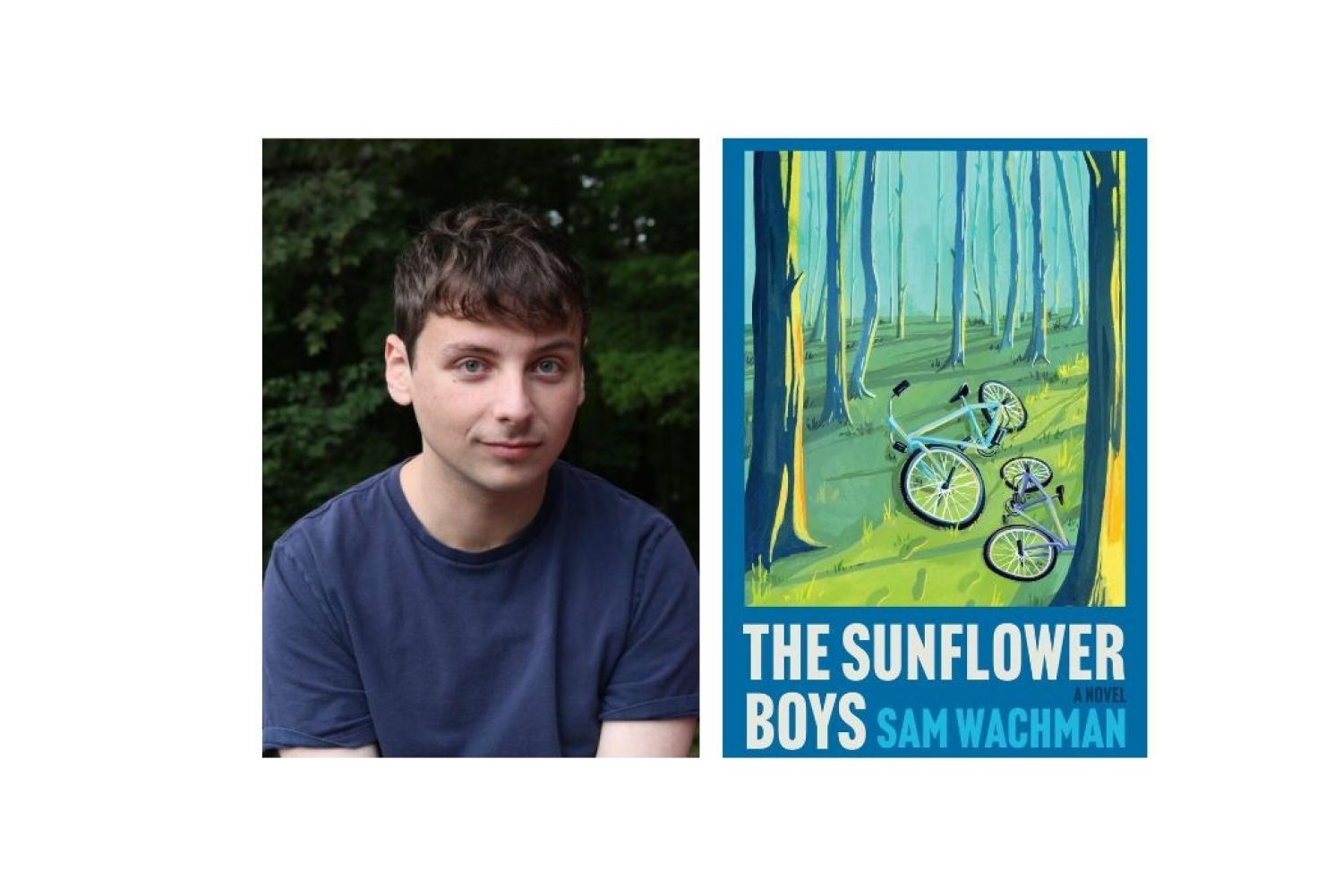

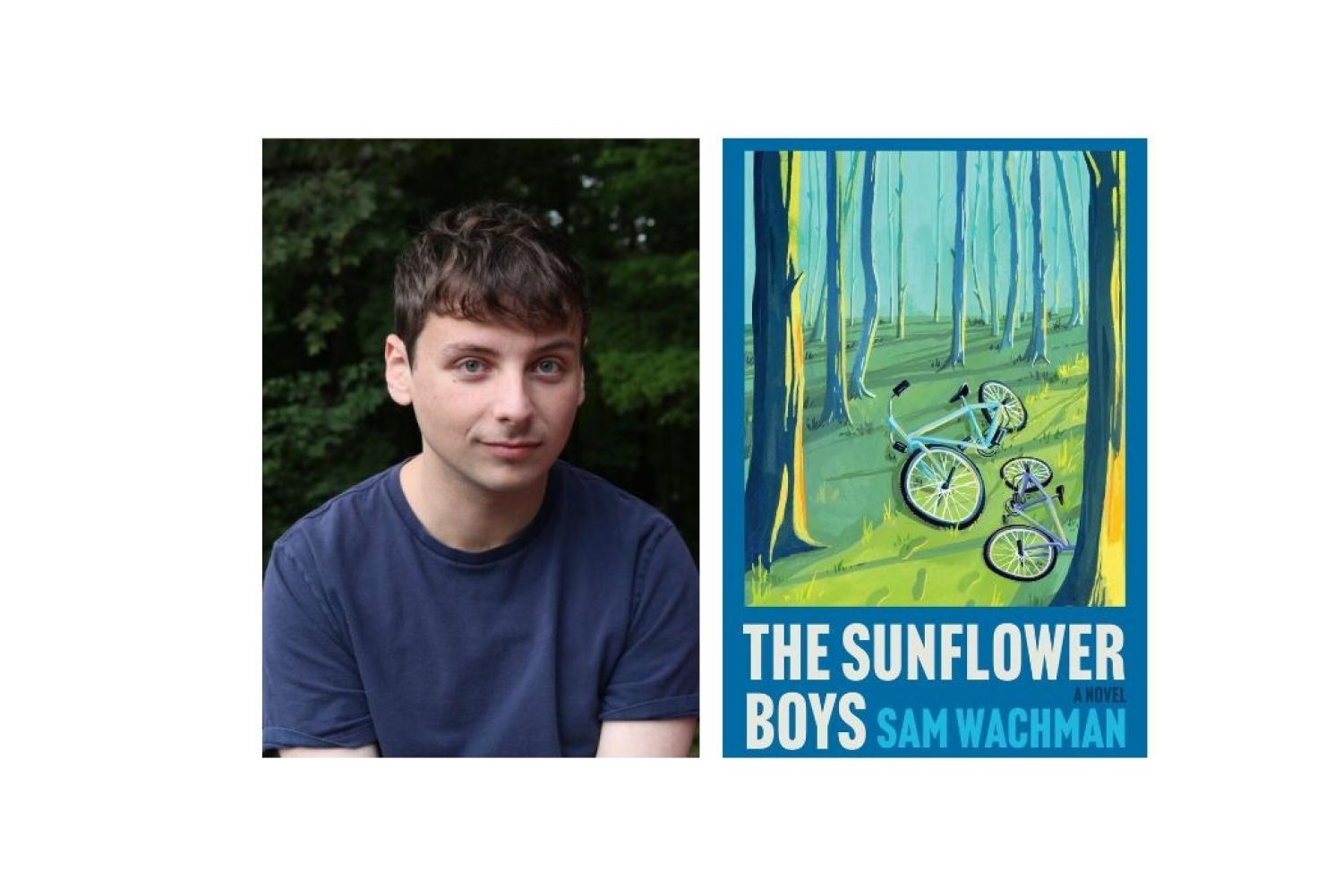

The Sunflower Boys is a novel that traces Artem – a young boy growing, stumbling, aching and falling in love in all the ways a young boy should. War interrupts that story halfway through, destroys it and leaves Artem blinking in the rubble. We’re in conversation with Sam Wachman, the author, about articulating queer identities, the grief of war, and the creation of his debut novel.

What drew you to tell this story of young, queer love?

I set The Sunflower Boys in the region of Ukraine where my family came from. I returned as an adult to teach English at a one-room schoolhouse. The kids I taught ranged in age from Artem to Yuri. I have always been open about my own sexual orientation in the Ukrainian cultural context; I don’t lead with it, but I won’t deny it if it comes up. Perhaps because of this, one of my students confided in me about their own sexual orientation. It struck me how radically their experience differed from my own.

I grew up in a (very) left-wing family in a progressive American city. In 1996, four years before I was born, my mother – an elementary school teacher – appeared in a documentary called It’s Elementary, in which she advocated the inclusion of gay and lesbian issues in the curriculum. For me, coming out was a non-issue. On the other hand, this kid was growing up in a rural region of a country where – at the time – the majority of the population explicitly opposed homosexuality.

This inspired the first few drafts of The Sunflower Boys, which I wrote long before the full-scale war. Those drafts revolved around Artem’s realization that his relationship with best friend Viktor transcended simple friendship. I focused on Artem’s struggle to reconcile that with cultural expectations of boys and men. I especially wanted to spotlight Artem’s relationships to the three most important males in his family: his deeply loyal and non-judgmental little brother, Yuri; his father, who was working abroad and whom Artem hadn’t seen in many years; and his grandfather, who embodied Ukrainian masculinity in its most traditional form.

How did you navigate writing about such emotionally tense themes such as grief and trauma through the eyes of a young boy?

In 2022, I was living in Denmark to finish my degree. On the twenty third of February, one of my students texted me because he was nervous about a competition the next day. We chatted for a little while, then said good night. He called me nine hours later. The competition was cancelled and he was with his family in his basement. There were missiles flying. That was how I found out about the war.

From that moment forward, I’ve seen the war primarily through my kids’ eyes. I had already written the first part of The Sunflower Boys when Russia invaded. That story belonged to Artem – a young boy growing and stumbling and aching and falling in love in all the ways a young boy should. War interrupted that story halfway through, then destroyed it and left Artem blinking in the rubble. In the words of Eglantyne Jebb, every war is a war against the child.

I see a parallel in my students’ lives; war forced them to skip developmental stages, to expose themselves to violence and shoulder inappropriate burdens. They conveyed their experiences to me every day. All I did was gently fictionalize those experiences and turn them into a single cohesive narrative.

What kind of research did you undertake as you wrote the book? Tell us about your writing process.

I didn’t have to research much for the first half of the book (the part set during peacetime). I was intimately familiar with the setting and culture I wanted to depict. Occasionally I double-checked with a Ukrainian friend to make sure something rang true. When Russia invaded, I stopped writing for a year. I flunked that semester of college in a pretty spectacular way. I met my friends and my students and their families in train stations across eastern Europe. I volunteered as a medic and translator. Writing felt frivolous.

One year after the invasion, I volunteered at an academic camp for Ukrainian kids in Romania. Somewhat miraculously, all of my students were able to come. One evening, we were sitting around having tea and playing Uno. My students were exchanging war stories with startling nonchalance and wry humor. I said something along the lines of: ‘You guys should write a book.’ And one of my students said ‘You do it. We’re busy.’

So that lit a fire under me. I spent March through September of 2023 finishing my first draft. I wanted to bring both Ukraines – peacetime Ukraine and wartime Ukraine – into one work. But I was far less familiar with wartime Ukraine, and it was far more important to be accurate. I drew a few details from an academic paper, Svitlana Makhovska’s ‘War cannot be understood, it must be felt’: 36 Days of Occupation in Chernihiv Region. But mostly I conducted interviews. I bought one of those voice recorders and fuzzy little microphones that journalists use, and I interviewed friends, students and strangers. A few dear friends who survived war crimes were willing to share their experiences in detail and allow me to use them in my book, which was unbelievably generous of them.

Probably the single most important interview I conducted was with a friend of a friend who escaped Ukraine on foot. We sat for four hours with my microphone and his contour maps of the Carpathians, and he walked me through every step of his journey. I took all of the logistics and details from that interview to write Artem, Yuri and Tato’s exodus from Ukraine.

“I see a parallel in my students’ lives; war forced them to skip developmental stages, to expose themselves to violence and shoulder inappropriate burdens. They conveyed their experiences to me every day. All I did was gently fictionalize those experiences and turn them into a single cohesive narrative.”

The book is set in the backdrop of a Ukrainian war — how did you balance the protagonist’s queer identity and his identity as a Ukrainian boy?

To me, the way in which these two aspects of Artem’s life interact Artem is a Ukrainian boy in love with his best friend, who also happens to be a boy. There are thousands more Artems in Ukraine. There are Artems in every country in the world. War robs Artem of the opportunity to continue developing and understanding who he is, and maybe even to achieve closure with Viktor. I’m not sure what form Artem’s national identity takes while he still lives in Ukraine. He’s never been abroad; he’s never been a foreigner. Fish don’t know they’re in water.

It is true that Ukraine has historically received boys like Artem poorly. Attitudes are improving, especially among younger generations. Just a few days ago, a Ukrainian court recognized a same-sex couple as a legal family for the first time. I do know that, to Artem, Ukraine has nothing to do with geopolitics. Ukraine is his apartment building, the river where he swims, his grandfather’s farm. His national identity is tied to family and place more than flags and politics. I wanted to maintain that ethos in the novel as much as I could, even in the shadow of war.

What were some of your inspirations; literary and otherwise, going into this novel?

Literary: The novels Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz J?drowski, The Toreadors from Vasyukivka by Vsevolod Nestayko, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, and Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury.

Otherwise: My former students and eternal friends: Artem, Vova, and Yasha. And Maksym, who is my real-life Yuri.

What do you hope young readers, especially queer readers and those from conflict zones, take away from this story of resilience?

I want to show the English-speaking world what a peaceful Ukraine looks like. I want them to know what has been lost and what still must be fought for. I also want to portray tender, nurturing relationships between brothers and between fathers and sons, when so many fictional relationships between boys and between men are defined by rivalry and acrimony.

Most of all, I am always trying to write toward peace. Good literature should draw upon the shared undercurrent of human experience. Good literature is the antithesis of violence. But I have released my novel into the world, and now only the world can decide what to take away from it.

What are you working on currently and what is the future looking like?

If only I could tell you what the future looked like – I could save lots on therapy. But I hope there will be a second novel.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 19-8-2025