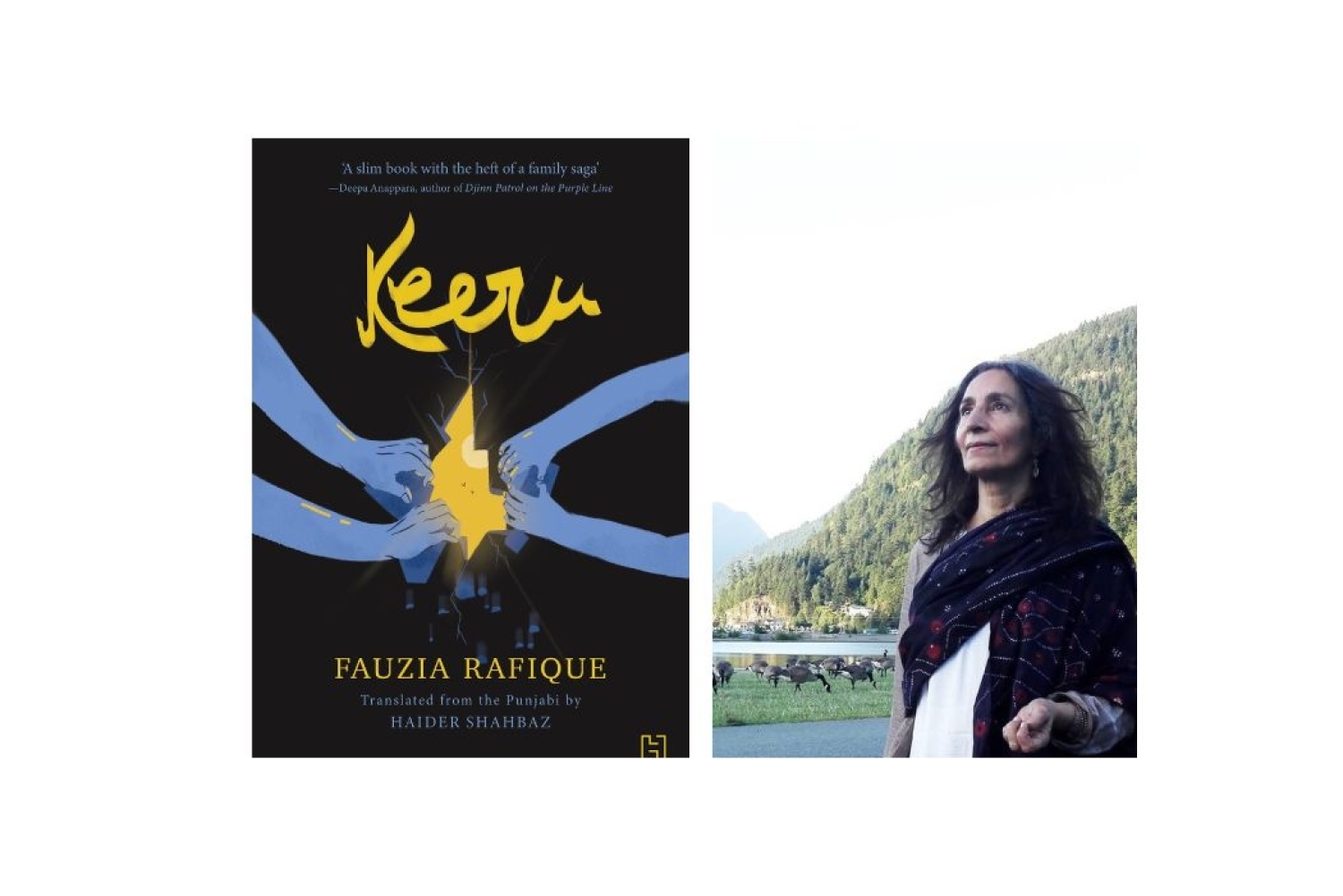

In Keeru, author Fauzia Rafique builds a world that traverses the fault lines of class, caste and power. Originally penned in the 1970s and completed many years later, this book tells a story of politics of the past as well as the present. It is an unflinching portrayal of resilience, and brings together the voices of five distinct characters within a world where the overlooked, vulnerable and defiant fight against systemic injustice. Translated into English by Haider Shahbaz, Keeru is feminist, queer, emotionally resonant, and pushes us to use our power to find family, love and hope – sometimes a world away. We’re in conversation with the author about the creation of this magical book and all the stories that lend to its fibre.

Where did the idea for this novel come from? Take us right back to the beginning.

This novel began to take shape in the tumultuous yet highly inspiring time of the 1970s when the stratified world was forced to witness powerful movements of students, workers and peasants demanding equality and justice by calling an end to systemic prejudices and different forms of exploitation of people. Hippie culture exposed the bigotry of ruling elites and middle class value systems. In the general elections in Pakistan, for the first time, some individuals were elected from classes other than the traditional powerholders. At the same time, as a young person, my hopes for a better world were dashed over and over. Bhutto, the ‘people’s representative’ in the then West Pakistan refused to relinquish power to the elected representative with clear majority supporting the West Pakistan army to invade East Pakistan causing the country to be divided instead. Upon usurping power, he began to attack popular movements and organizations of workers, peasants, students. This novel was to expose and confront the many betrayals of Pakistan’s ruling classes.

The title is loaded with metaphor. What do insects represent for you, within the context of this story?

Most insects live and operate underground assuring the survival of their species. Though usually small and seemingly insignificant, their contributions to the world are profound and life-affirming. Just consider the roles played by ants and honeybees, for example.

Why did you choose to tell the story from so many different perspectives? Tell us a little about the narratorial voice of this novel.

I was always uncomfortable with omniscient, all-knowing, all-powerful author/narrator who represented everyone and everything in a story. My other two published novels are narrated by single protagonists telling their own stories. When I began writing Keeru in the mid-70s, it was being told by the character Keeru, and the first six or so chapters are written that way. But when I began to work on it in the late 2000s, I could not reconcile with Keeru telling the story, for example, of his mother. Why not let Haleema tell her own story? In fact, to me it was unfair to make any of the five protagonists of Keeru to be represented by another character or by the all-knowing author/narrator. Keeru, Haleema, Naila, Daljit and Bella all have diverse experiences and unique voices. It was a pleasure for me to explore each and to see them emerge on the page. The challenge was to make the story progress and the plot to continue to move forward without making it cumbersome or disruptive for the reader. There was the risk that it may not work at all. But it did.

Keeru is certainly a story of resilience — what does hope look like for your characters, and for you as a writer?

Hope is a tree growing out of dirt using water from the rain and light from the sun. Grounded, self-caring and reaching, it nurtures all life on earth.

“Hope is a tree growing out of dirt using water from the rain and light from the sun. Grounded, self-caring and reaching, it nurtures all life on earth.”

What were some of your inspirations for this novel?

The real Keeru and his mother. I came to know them as a child when Keeru was a toddler and his mother a young servant. As a child in the 60’s Lahore, I met a toddler named Keerru, the son of a new domestic servant, a live-in single mother working tirelessly day and night to finish all the unending chores while her baby was left sitting naked in the verandah calling her and crying in a low voice so as not to disturb the ‘boss’ family. The toddler had a bloated tummy and skinny arms and legs, that even as a child I could identify as signs of starvation and malnutrition. He never smiled or laughed or played, only whined, wept or cried fixated on two things, his mother and food. I did not pity him, I feared him. Sometimes, he would forget crying to gaze at something with his small piercing, jaundiced eyes making me cringe with an undefined apprehension. Both stayed for a few years and then disappeared from our lives — but never from my mind. Keerru’s existence is etched on my mind as is the humility and resilience of his mother. A few years later, I saw them again. His mother was the same humble and strong self, in better clothes. Keerru was a short young boy, fully clothed, hair combed, same small but piercing yellowed eyes, now he had a constant grin on his face and a crazy laughter. He still did not speak much but when he did, his voice was loud and clear. That time, it seemed to me as if Keerru could become anything — a criminal to a saint.

What do you hope readers take away from the story?

Joy, first of all, of reading the story- and then healing. It ought to be a healing experience for the reader. You may think such objectives are contradictory since the characters experience atrocities such as poverty, resourcelessness, blasphemy, religious persecution, colonization, gay bashing, woman abuse, class/caste prejudices and other systemic barriers. And that’s precisely why reading this story must bring joy and healing to the reader.

What are you working on now, what does the future look like?

There’s a beautiful YA fantasy at the editing stage, a realistic present-day novel in the works, and a collection of Punjabi poems ready for print. The future feels enticing.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 5-8-2025