Photograph: Clayton Cubitt

Photograph: Clayton Cubitt

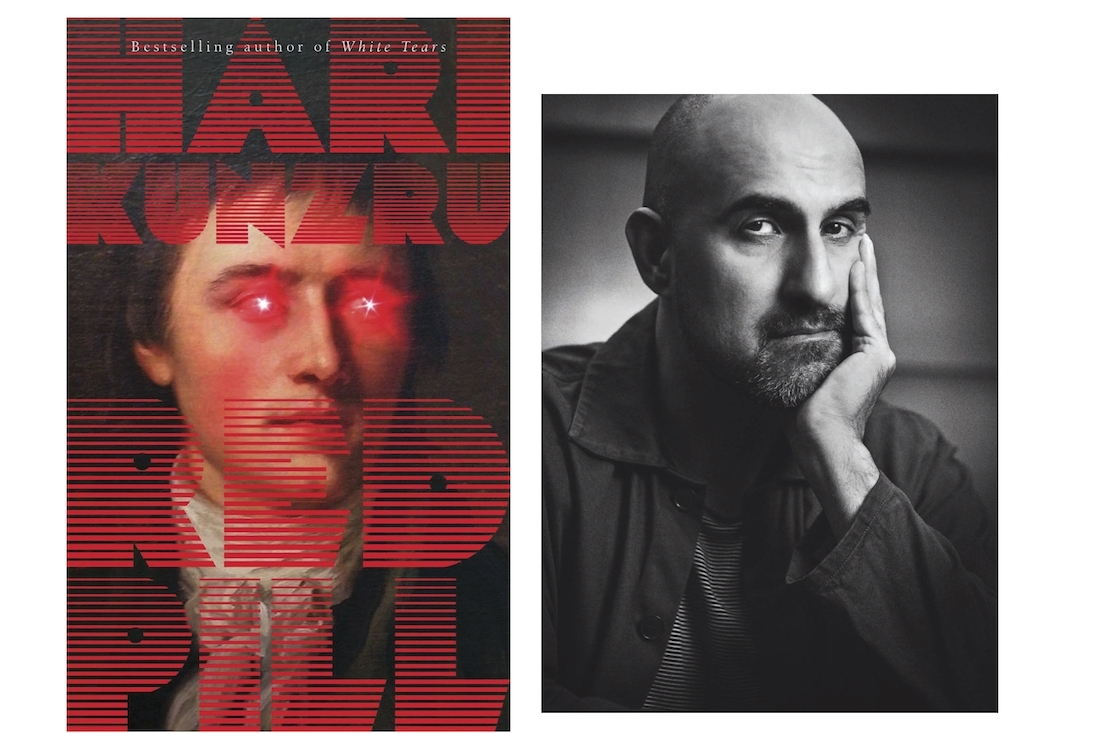

At the heart of ‘Red Pill’, lies the experience of a British-Asian man trapped in a mid-life crisis, triggered by a sense of impending doom. It is the year 2016 and the world is witnessing a radical socio-political transformation. The US Presidential election is only a few months away. The status quo of normalcy is rudely being elbowed out by a new-fan- gled world order.

Hari Kunzru’s novel is immensely layered, packed with themes of State surveillance and privacy, racism and feverish paranoia, the far-right intellectual milieu online and fleetingly, about the refugee crisis. However, it also powerfully explores the emotional arc of what it means to be a man providing for and protecting his family, trying to live up to the inflated expectations of masculinity in the 21st century.

The novel is primarily set in suburban Berlin, Germany, where the unnamed narrator, a Brooklyn-based ‘independent scholar’, attends a three-month writers’ residency at the Deuter Centre in Wannsee. “Berlin is really a city of ghosts,” explains Kunzru. “It’s a city where you can’t escape the spectres of its fevered past. The book has allusions to the Nazi regime’s Final Solution and an autonomous section dedicated to East Germany during the Cold War.” Kunzru uses that fertile history to stir readers to reflect deeply on the current circumstances. “I’ve used the past to illuminate questions in the present,” he explains. His novel, therefore, is a literary red pill; an attempt to knock down the saccharine mirage of complacency in which we are all living. Platform gets on a call with Kunzru to speak to him about his latest literary offering and his brand-new podcast, Into the Zone. Edited excerpts:

How did the idea for ‘Red Pill’ come about?

I took my family to live in Berlin for six months, because I had a fellowship at an institu- tion called the American Academy in Berlin, which is on the shores of Lake Wannsee. It’s in an old villa that invites scholars, artists and writers and you live together in this community for quite a long time and you eat meals together. What I did was that I invented the institution, Deuter Centre that had the same physical location along the lake, but otherwise has nothing to do with the American Academy.

I was in Berlin just at the end of 2015 and first half of 2016 and I was thinking in a very anxious way about the future and about the larger, sociopolitical changes that were going on in the world. Then I began to think about the history of Berlin. Of course, Berlin’s history involves the Nazis and it involves communism. The Germans have a very strong sense of privacy and they have a very strong sense that the individual has to resist some state power. So, all these things were roiling around in my head. The idea of having my narrator go off to Berlin to think about his life and his relationship with his family...that was the start of it.

The pages are littered with ominous, historical references. There is the mention of the Final Solution, for instance. What was the atmosphere that you were trying to create?

I have two young children right now. When you are a single, young man in the world, you are pretty used to being relatively strong and secure about yourself. You can safely walk in places other people can’t walk in. Then suddenly, when you become a father, there you are with these precious creatures that you care about the most and you realise that you haven’t ever experienced that kind of vulnerability before. It is very, very striking, I think, for a lot of men, but it’s not something I’ve heard people talk about so much. You have a terrible sense of responsibility to keep your children, your family safe.

That started making me think about larger questions of safety and dealing with unexpected things. I’m fifty years old now. I spent my twenties in the UK, back in the 1990s. It was a relatively positive period; I would say that it was a very good time for British-Asians. Suddenly, we were very visible and we were confident. There were a lot of us creating music and art. It was a really great moment to be brown and young.

However, things have changed since then. Politics has become much darker. Authoritarianism has reared its ugly head all over the world. We are in a time of greater uncertainty than ever before and it’s a very strange time to be thinking about the future. Whether it’s here in New York, or when I talk to my parents in London, or when I talk to my cousins in Bombay – everybody’s anxious. I wanted to try and write honestly about that feeling. The core of the book for me is that anxiety.

The narrator is quite an unlikeable and unreliable character. He’s someone who walks while always looking over his shoulder, he lives sloppily and even abandons his wife and child. Is he a patchwork of people whom you’ve met?

In many ways, he is a worse version of me. It’s a book about mid-life crises. Most men’s stories about mid-life crises involve some sort of sexual straying. It’s all about, ‘Oh, Iam unhappy in my marriage, so I am going to have an affair and maybe that will change things’. However, I wanted to write about a crisis, which happens to a man who really loves his wife and child. He never stops loving them, but he feels that in some way he has let them down, just by existing.

That’s the core that he feels is wrong with him and he unravels as the book goes on. He’s carrying this shameful feeling that, in some ways, he’s not up to the job. That his wife will one day realise, ‘Oh, he can’t protect us, he can’t help us. He’s not going to be a man’, in that traditional sense.

So, that was another thing that interested me: how does a situation like this play out, if it’s not orientated around the clicheÌd story of sexual infidelity?

I say this because there are other kinds of crises, other kinds of situations where men feel they’ve failed. It’s really a book about masculinity and given how many men write books, it’s peculiarly limited how often they discuss their anxieties or fears.

Monika’s story is fascinating. As a teenage punk living in East Berlin during the 1980s, she was strong-armed into becoming a Stasi informer. How did her character come about?

Berlin is really a city of ghosts. You cannot not be aware of its past. As you walk in the city, you realise that there are holes in the buildings made by fifty calibre shell bullets from 1945. You look down at the sidewalk under your feet and there is an artist who has a project called Stolperstein (Stumbling Stones) where he set little square-shaped brass plates into the sidewalks, each bearing the name of a Jew who was taken from that address. The project commemorates them. Also, in terms of Berlin’s geography, you can still feel presence of the wall, even though it’s no longer there.

While I was living in Berlin, I was getting more and more interested about ques- tions of privacy, about the individual and the State power. I started reading about the Stasi and how they monitored and surveyed artists and creative people in East Germany. I thought I might write something about an artist or a poet – somebody who was close to the kind of work that I do. And then I started reading about what happened to the punks in East Germany. These were really young people, teenagers most of them and yet the State considered them to be a serious threat. The more I read about them, the more I became fascinated by their world.

I wanted a story that was kind of a wedge into the main story – like a free-standing novella inside the novel. So, I wanted Monika’s experience to be a comment on the nar- rator’s experience, because she’s gone through so much more. You learn that she’s been very traumatised by what has happened to her. So, that was the relationship between her story and the narrator’s story.

You did this because you were interested in drawing parallels between the past and the present?

Yes, absolutely. It’s something that I’ve done in a lot of my fiction. I’ve used the past to illuminate questions in the present. As a fiction writer, I like imagining my way into thesealternative systems. It’s a very interesting exercise for me to imagine how I might have behaved if I was living under a particular kind of regime. What would be the actual pres-sures? What would be the actual decisions that I’d make?

Crippling paranoia and mental breakdown are at the heart of ‘Red Pill’. What drew you to these themes?

I’ve been living in America for the last twelve years. Americans have a picture of the world in terms of what they think is possible that could happen in America. For those of uswho’ve come from outside, our picture is slightly different. We are often quite surprised at how firmly they believe in their systems, their traditions and how robust they thinkthey are. What we’ve discovered in the last four years is that those systems and traditions are not robust. The experience has been of a country in collapse.

There is a writer called Nassim Nicholas Taleb who talks about the Black Swan event, which is the unexpected event that destroys all your predictions of the future. I think we are at a moment where all sorts of things, which once seemed unreasonable and impossible and were the products of paranoid fantasy, are now in full flight. Just a fewmonths ago, there were unmarked cars in New York and Portland picking up (Black Lives Matter) protestors off the streets. We have also a completely failed response to the pan- demic where people are looking at being in quarantine for another six months.

And so, I was interested in the idea of a person (the narrator) who is having a breakdown, but at the same time, the kind of apocalyptic version of the world that he is imagining seems more possible now than it ever did. Everybody I know lies awake looking at their phones, doing what is called ‘doom-scrolling’. People are wondering what the world would look like in ten years’ time, how far things will go? Suddenly, our ability to predict the future has failed us.

In your novel, Blue Lives is introduced as a series filled with violence perpetrated by corrupt cops. The series is reminiscent of the idea of ‘manufacturing consent’, which brainwashes viewers into thinking that violence for a greater good is justified. Is this a reflection of the current socio-political climate?

I certainly think it is. It’s a kind of show that I can almost imagine getting made, but not quite. I’m interested in the notion that in popular entertainment, there is politics – there is a point of view, which is always put forward. Certainly, here in America, thousands of hours of television are devoted to commemorating the cops, yet the current public per- ception of the police is changing. There is a tension between the policing we are seeing on the streets, which seems violent, confrontational and racist, as opposed to the police that we see on television.

There has also been a change in the entertainment culture. You have to tell me whether this is true in India, but over the last ten years or so, I’ve seen a more kind of realistic gangster movies and series like Sacred Games, coming out of India, which are quite popular. That reflects a kind of cynicism that is involved in people’s thinking about reality. Certainly, in America, cable TV shows and streaming platforms are releasing content that has a much bleaker, more brutal and cynical view of the world and it seems to be suiting people’s taste.

People tell themselves that they are more sophisticated for watching such shows, rather than watching an old-fashioned show about the goodies and baddies, which have an easy moral ending. But I wanted to see how we consume these cynical stories that make us believe that the world is corrupt, that we can’t do anything about it and that crime will always triumph. Which is what the series are selling: a kind of hopelessness. It’s making us more passive in the face of global issues.

Every time someone says on twitter, ‘Oh, I’m very shocked by this XYZ event’, someone else will respond saying, ‘Huh? You’re really shocked by that one?’ I want us tomaintain that sense of shock, because I feel that without that sense of shock, you don’t have a moral compass. One of the reasons for inventing Blue Lives for the book was to think about entertainment and cynicism and the smuggling in of political messages.

You also recently launched your own podcast called Into the Zone. Could you talk about that?

I’ve been working really hard on this for about a year. It’s been made with a production company set up by non-fiction writer, Malcolm Gladwell and Jacob Weisberg who set upSlate. They approached me saying, ‘We’d love you to make a show for us. It can be about anything that you like; we want you to tell compelling stories about the things that inter- est you.’ That seemed like an extraordinary offer to me.

This podcast is really a wide bunch of different things. There is a show about the Stasi surveillance and the punks, about Berlin and the public and the private. There is a show about new discoveries in genetics, there is one about who is a native and who is a migrant, which also explores my childhood in England and then being told to, ‘Go home’. I also travelled to different places to interview people. I did go back to Berlin and I went to Paris to talk to an artist. It’s really a beautiful production with music scoring andsound effects. I can’t wait for people to hear it.

This conversation is an all exclusive from our November Bookazine. Grab your copy here.

Words Radhika Iyengar

Date 20-03-2021