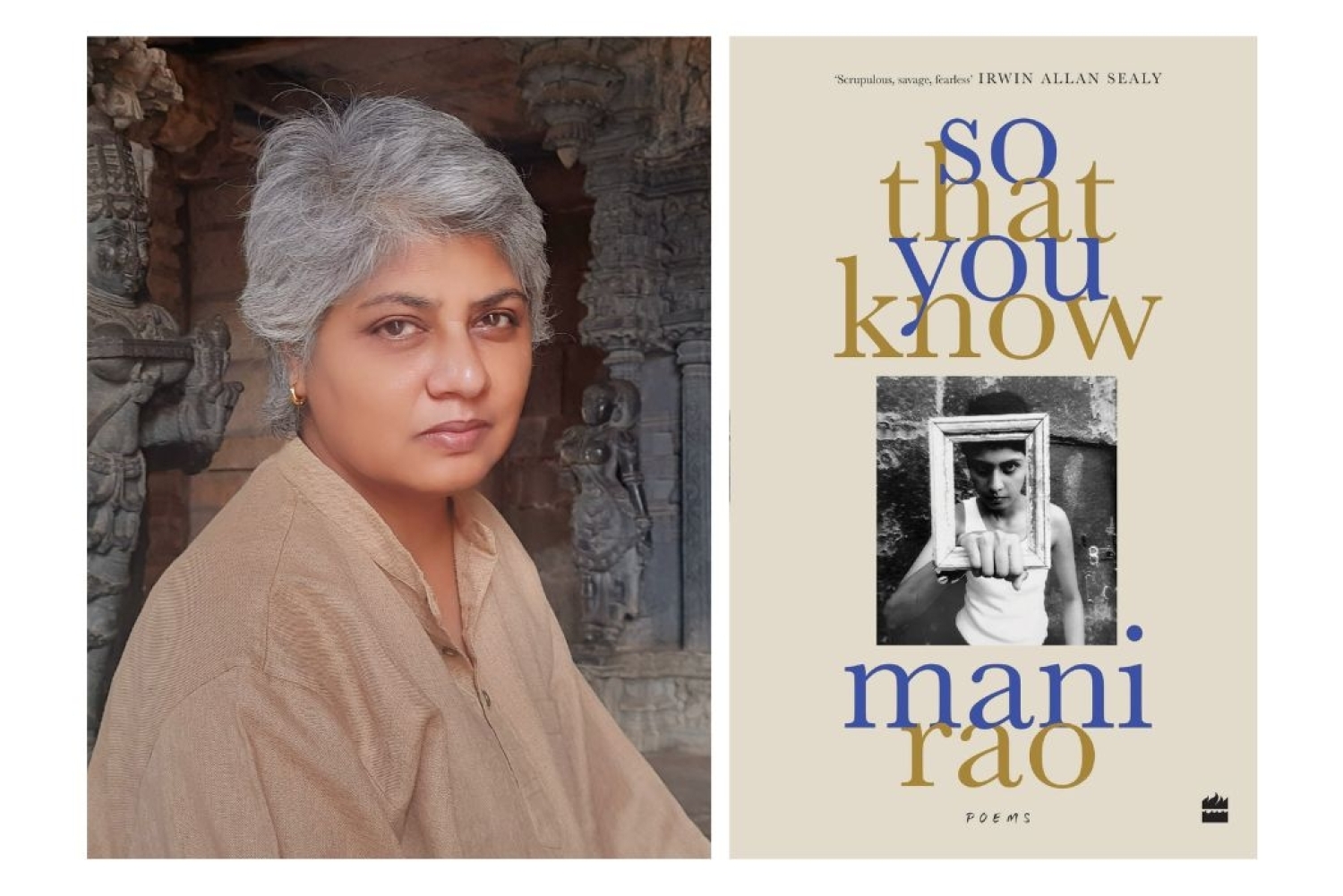

Photo by Sujata Mukherjee

Photo by Sujata Mukherjee

Mani Rao’s So That You Know is a force to be reckoned with. This poetry collection is dazzling, witty and experiments with form and language. Some of these poems have been written over the past 40 years, and are a fascinating journey of the writer’s past and current selves. There is something about her poetry that keeps you going back to these pages for more and more. These poems are intimate, and include observations on memory, the body, beauty and nature. When we asked her how her poetry comes to life, she said, ‘Things that strike me, or bother me, momentous discoveries in daily life!’ Many of these poems transport you into their worlds with ease, which is to say being within these poems is a privilege and a joy.

We spoke to the poet about her relationship with writing, writing process and the creation of this collection. More below.

What is your relationship with poetry and writing?

It is what I do. And by that I do not mean that I am restricted to a defined genre of ‘poetry’, for I understand that word quite broadly. Nor do I mean I am constantly ‘writing’. What defines my work is language itself - it is an intense space. Therefore, poetry becomes the medium– poetry is a precipice of language.

How do your poems come to life? Take us through your writing process.

Things that strike me, or bother me, momentous discoveries in daily life! Sometimes I scribble, I may scribble a lot and eventually only keep one or two lines from it for future use. Trash the rest. Sometimes, when the inspiration (or provocation, or disturbance – basically the source, the cause for the poem) has been festering, it may get edited mentally, and by the time it surfaces on paper it is a single shot– no editing is required. Such poems tend to be short and distilled. When I begin a longer poem, I know the theme and am working at jotting impressions (from memory or imagination), expanding the narrative in different directions, or adding joineries to create the body of the poem. Such a poem will go through a few revisions. In general, editing makes the poem. Sometimes leaving a spark alone is the most important thing.

Many of your poems embrace ambivalence, resisting certainty and leaving space for multiple interpretations. Why is this space of not-knowing important to your poetry?

Not knowing is how we are. Of course, it is also valid if a poem pretends to know everything– but those poems usually present an argument, or take a stance, and they may even try to persuade. There’s not much room for the reader (nor can the writer move too much).

I place a lot of importance on suggestion, and resonance. It is when imagination joins language, that resonance occurs.

Finally, it is because I ignore the reader that the reader gets to participate as much. I mean, that when my reader is me, I don’t need to spell out everything. I am trying to discover something (a situation, a potential, a space). Then, when the reader arrives at the poem, they begin to as if complete the poem from their own positions.

How do you arrive at your poetic subjects?

I don’t recall any moment when I thought something was not fit to be ‘a poetic subject’-- perhaps it’s because in most poems I’m not determined on what I’m writing about.

Who are some writers you find yourself turning to for inspiration?

I’m inspired by many writers, it’s hard to pick a few. Paul Valery’s vision, Ezra Pound’s effort and scope, J Krishnamurthy’s probing.

Many of these poems are memoir style, in that they document your observations and interactions from everyday life—do you think of poetry as a mode of documentation?

It is also that, and that is an important role. But no documentation arrives without an interpretation and perhaps the documentation is merely the excuse to deliver the other part– the voice, or the vision.

Tell us about the story behind the title So That You Know.

It is the title of a poem in Ghostmasters (2010)-- in a way, I stole it from myself. (Oh yes, I changed the title of that poem when I included it in this collection). It’s because this book includes poems from across all my books, it felt like a summary-moment; here was a long story being shared with the reader.

A poem you’ve loved as of late?

Now to find an answer to this, I picked some books from my shelf and leafed through them. Here is a line I saw in Lisa Robertson’s book Debbie. She quotes Theodore Adorno: 'I did not yet admit to myself the complicity that enfolds all those who, in face of unspeakable collective events, speak of individual matters at all.'

What are you working on next, what’s the future looking like?

I do have some ideas crowding my mind, but I don’t yet know what is apt and what needs to be done by me next. The future is bleak. We hope love will prevail. Do you mean my future, or a future writing plan? I have no idea, and that is a good thing.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 29-09-2025