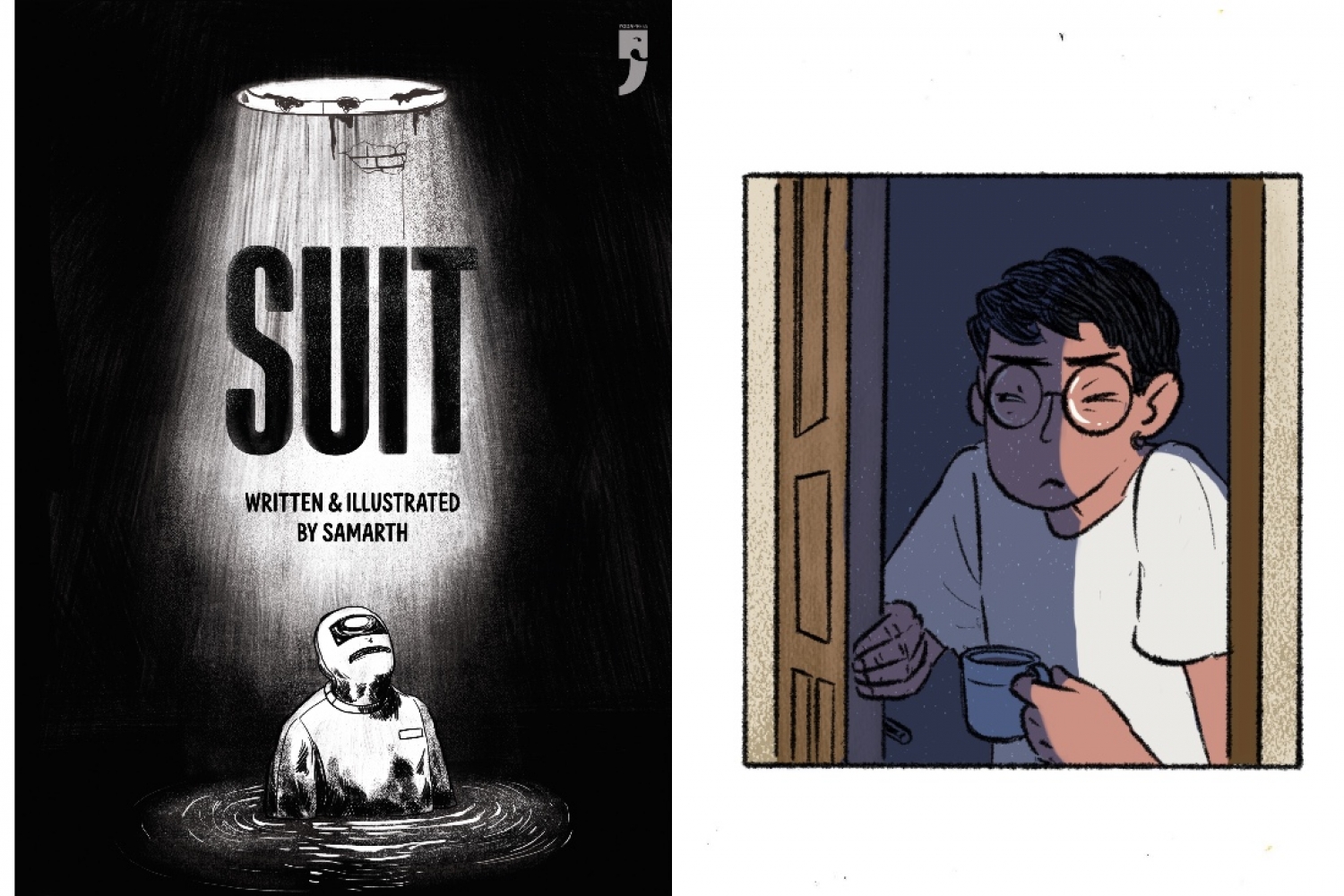

The genre of graphic novels can be really hard-hitting. A graphic novel has the power to pervade your reality not just through words, but also imagery, propelling you more urgently into the exploration of the novelist’s intended thematic concerns. And when these thematic concerns include subjects that we routinely endeavour to erase from our collective consciousness, seeped in exploitation and oppression, the graphic novel becomes even more powerful. Such is the case with Samarth’s debut graphic novel, Suit. In this ingenious feat of storytelling, Samarth conceives of a future where the lives of Safai Karamcharis are led towards a change with the introduction of a full body safety suit. This promptly also changes their designation to Suitwalas. However, through the pages of the novel, the inherent stigma that encompasses the lives of Suitwalas, and our current waste and sewage workers, slowly becomes super-saturated.

I connected with Samarth to know more about his novel and its creation. Excerpts from our conversation follow:

How were you led towards the world of illustration and graphic novels?

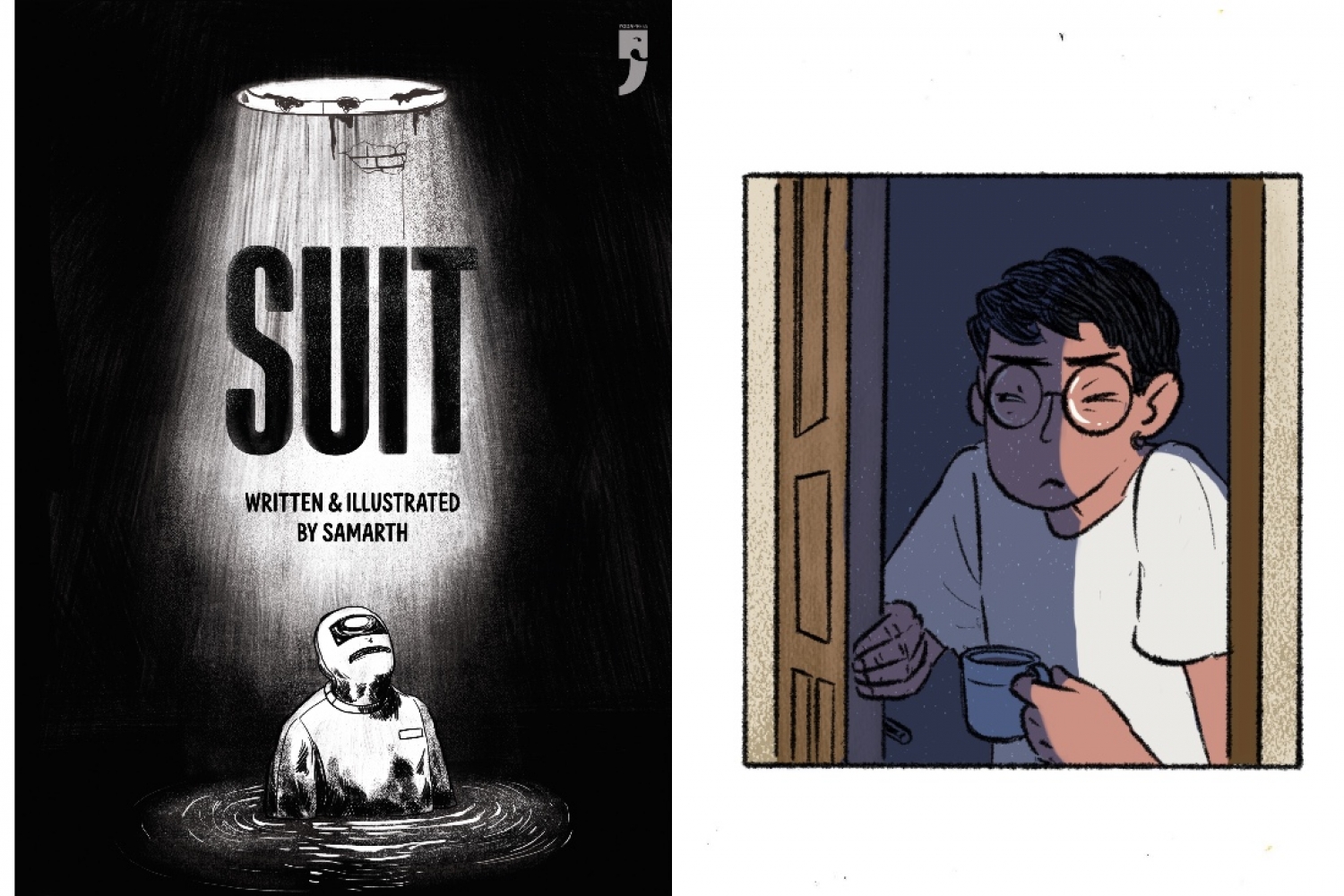

I have always loved drawing ever since I was a child. It was just a very easy manner of interpreting everything I saw around me. Thinking about it now, I think I always found it much easier to depict what was in my head than draw with references. But it was mostly this familiarity with the medium that got me into illustrating in college. Similarly, stories have always been so central to my childhood. I love reading, and it was probably the easiest of escapes back then, to slip into a world filled with beings, their joy and sadness, their fascination and/or disappointment with the world around them. So, through most of my time in design school, I tried understanding stories, tried telling them. I dabbled with animation, film making, picture books and comics. As I got a better hang of the craft, and tried several balancing acts, I finally decided to try my hand at graphic novels. What I liked the most about them was that they were such a perfect blend of that immersive visual experience that films can provide you, while having so much room to play between the panels and between the pages, and having complete control over the depiction and representation. It was quite an exciting realisation.

What is your debut graphic novel, Suitʼs, origin story?

Suit was an outcome of a project I had taken up in the final year in the IDC School of Design in IIT Bombay. I was thinking about the themes of violence and oppression, which I was deeply bothered by. It was just after an exchange programme to Israel, when a friend of mine and I volunteered in Palestine for a month, and happened to see what life within oppressive and cruel systems can look like. I had approached Sudhanva Deshpande of the Jana Natya Manch to discuss my experience in Palestine, since he had also been involved with cultural exchanges with the Freedom Theatre in Jenin. I think, spending several hours sitting in Mayday Books, talking to Sudhanva, and just orienting myself to an entire reinterpretation of the world around me, was crucial to the trajectory that led to Suit. Digging deeper into the various faces violence takes in society, it was clearly evident that caste, class and patriarchy were central to the violence unfolding. And thatʼs mostly because of the nature of violence, as it is an outcome of inequality, of one person feeling like they have more of a right or a claim to something than another.

For me, at that point, to really understand the shape that violence takes in our society, I had to find a point of confluence that really defines the extent to which oppression can be internalised and taken as a part and parcel of a democratic society. Out of the many that exist, manual scavenging and conservancy work has always been one of those aspects of our society that always feels like the darkest blotch on the values our society holds. Ever since I saw Sudharak Olweʼs photo essay, In Search of Dignity and Justice, it has been a reality that I have been painfully aware of and since the photo essay is based in Mumbai, the city where I grew up, these images felt like pieces of a picture that I had missed the entire while I lived within the comforts of my class and setting. This photo essay was also what led me to the Kachra Vahatuk Shramik Sangh, KVSS, which is a labour union of Safai Karamcharis in Mumbai. Milind Ranade, the union leader, who is extremely warm and encouraging, spent a lot of time taking me through the myriad of problems they have been fighting, case by case, over several years. Mahindra Kamble, the representative of Safai Karamcharis from the M(East) ward in Mumbai, was extremely kind and accommodating, allowing me to accompany them as they did the rounds of Mankhurd during their shift. It was here, during these rounds, that the initial ideas of Suit started crawling out. Although this project was mostly conceptualised and pieced together in college, it took an entire year after I graduated to have it completed.

What is at the novelʼs core?

I think Suit is a story of hope. Itʼs a piece of speculative fiction that tries to portray a future when Safai Karamcharis are provided with safety equipment and social mobility. But that isnʼt why I think of it as a story of hope. I think in the creation of a narrative that can imagine a future in a reality that we fail to acknowledge or address, it opens up the possibility of bringing the community of Safai Karamcharis back into our imagination. For the character Vikas, a young Dalit man who is a Safai Karamchari, or rather a Suitwala, in the book, to find life and meaning in our minds through the reading of this work is something that gives me immense hope. And thatʼs the hope that fiction provides. Of imagining futures which we have denied by our ignorance and indifference. The story does not advocate directly, but it joins other such works that have been made in the past, and that people are making now, that bring this aspect of our society to the forefront, as something that needs to be spoken about and addressed.

Could you give us some insight into your creative process behind this bookʼs creation?

The first part, which is the conceptualisation of the story, happened to click in place soon after the initial work with KVSS. I was struggling to figure out how to speak about the theme of violence and the subject of Safai Karamcharis, considering my own position as a Savarna writer, who hasnʼt had to face these realities first hand. The story was not going to be about lived realities because, for me, it wasnʼt something that flowed out from the richness of experience, and it wasnʼt my story to tell. So instead, I decided to tell a story about a possible future. The approach was inspired by Isaac Asimovʼs short story called Strikebreaker, which is about a fictional society in which the sewage system of an entire planet is managed by one family, and although this family is provided all the material comforts of the world, they are ostracised by the rest of the community. They stay far away from everyone else, nobody speaks to them or of them.

After that I decided to work on a script, borrowing from the filmmaking workflow that I was a little comfortable with by then. Piecing the story together in literal scenes and dialogues was a major challenge, because of portrayal and representation. It required a lot of work, especially regarding my own position, to be able to imagine the characters and what their lives might be like if there were to be a change in the laws and policies. Then again, the story could in no way be detached from the political atmosphere of today. From the building of large statues, to the street-play inspired by the Kabir Kala Manch, to the peopleʼs movement that led to the introduction of suits in the story, all these things were happening in the spaces around me and they also found their way into the setting for Suit.

Could you acquaint us with any literary, artistic, or otherwise, influences that guided your work on this book?

There were several works that influenced, inspired and guided me in the making of Suit. As I mentioned earlier, Sudharak Olweʼs photo essay, In Search of Dignity and Justice, was one of them. Along with him, M. Palani Kumarʼs documentation of manual scavenging in Tamil Nadu was also a huge influence. The documentary film about the daily lives of manual scavengers, Kakkoos, which M. Palani Kumar worked on along with Divya Bharathi, was another major point of influence. When it comes to fiction, I think Nagraj Manjuleʼs films were so inspiring, especially Fandry and Sairat. Vinod Kambleʼs film, Kastoori, was another point of inspiration, as it depicted the lived realities of manual scavengers in rural India with such brutal and heartbreaking honesty. Balut, by Daya Pawar, and Namdeo Dhasalʼs poems, helped me align my own position so much. I realised how much of a separation exists within my identity as a Savarna author from the realities that they speak of, and how necessary it was for me to address my own identity before I approached this story I was hoping to tell.

Coming to graphic novels, the one that influenced me the most was Orijit Senʼs River of Stories. It was quite nice to come across a short format graphic novel that rendered the subject matter in black and white illustrations, mostly ink and pencil work, which reminded me a lot of Will Eisnerʼs renderings of stories in his books. Along with that, graphic novels like A Gardener in the Wasteland by Srividya Natarajan really guided me with understanding how the subject matter of caste has been covered in the graphic novel format. Bhimayana, which is illustrated by Subhash and Durga Bai Vyam, and written by S.Anand and Srividya Natarajan, was another such work. Of course, graphic novels like Maus by Art Spiegelman and Footnotes in Gaza by Joe Sacco were also quite central to me being able to appreciate the power of graphic novels.

What were some of the challenges you faced with this debut?

I think the question ʻwho am I to tell this storyʼ bothered me right from the time this story began to conceptualise itself in my head. To the extent that there was an immense paralysis. As someone who doesnʼt belong to the community, hasnʼt had to face this kind of degradation and humiliation on a daily basis, nor has been at the receiving end of institutional and societal violence, do I have a right to tell a story about a character that has faced this oppression first hand? What kept me going, and the thing that allowed Suit to keep shaping up, was this feeling of urgency, for these characters to create a future and to question what change might mean in such a future.

Itʼs also the knowledge of having a story that you feel needs telling and then not writing it. Especially when you see the lack of representation of such stories in popular formats, like graphic novels. It is an immense weight. And keeping quiet is a political statement, too, that I wasnʼt going to participate in. Iʼd rather tell this story and face whatever it is people have to say, than not tell it. Knowing that this story came from a position of solidarity towards the Safai Karamchari community and with an acknowledgement towards the role I play in witnessing this injustice as a member of the society that carries forward this oppression, the question flipped itself and became, ‘who am I not to tell this story?’

What do you hope the readers take away from this book?

I am not really sure what it is that I want people to ʻtake awayʼ from Suit. I think so much of the initial urgency with which Suit was first drafted slowly began to formulate into a prolonged seeking into the intricacies of caste and how it happens to shape so much of the world around us. From the few responses I have received, I think everyone has a different take away based on how much they know about the existing realities within the waste management and conservancy sectors. But this is when caste, class and stigma is represented in the starkest manner. The way it shows up in our everyday interactions, in our relationships, in our academic institutions and professional environments, in our homes, are things we know and observe but have not been able to shake off. If anything, I hope Suit allows us, especially the Savarna audiences, to be more vocal about caste and its implications. As a friend of mine in the student organisation we had on campus once said, ʻTo annihilate caste we must first speak about caste.ʼ It seems like the weight of caste always falls on those who fall outside the caste system. It almost always seems to be the weight that Dalits, Bahujans and Adivasis have to bear. And speaking about caste within Savarna groups, acknowledging our position and its implications might just divide the weight more evenly across our society.

The pandemic has been a rough patch, but it offered a lot of space and time to work on myself. I have been doing pretty well, managed to move into a new space with ample room for my books and my materials. Iʼm currently working on a few smaller projects, mostly comics, but Iʼm hoping to revisit a graphic novel I had been working on in the beginning of the pandemic. Itʼs a story based in Malvan, a coastal town in Maharashtra, where I was stranded for the first three months of the pandemic along with some of my friends who are marine biologists. Iʼm quite excited about that.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 17-02-2022