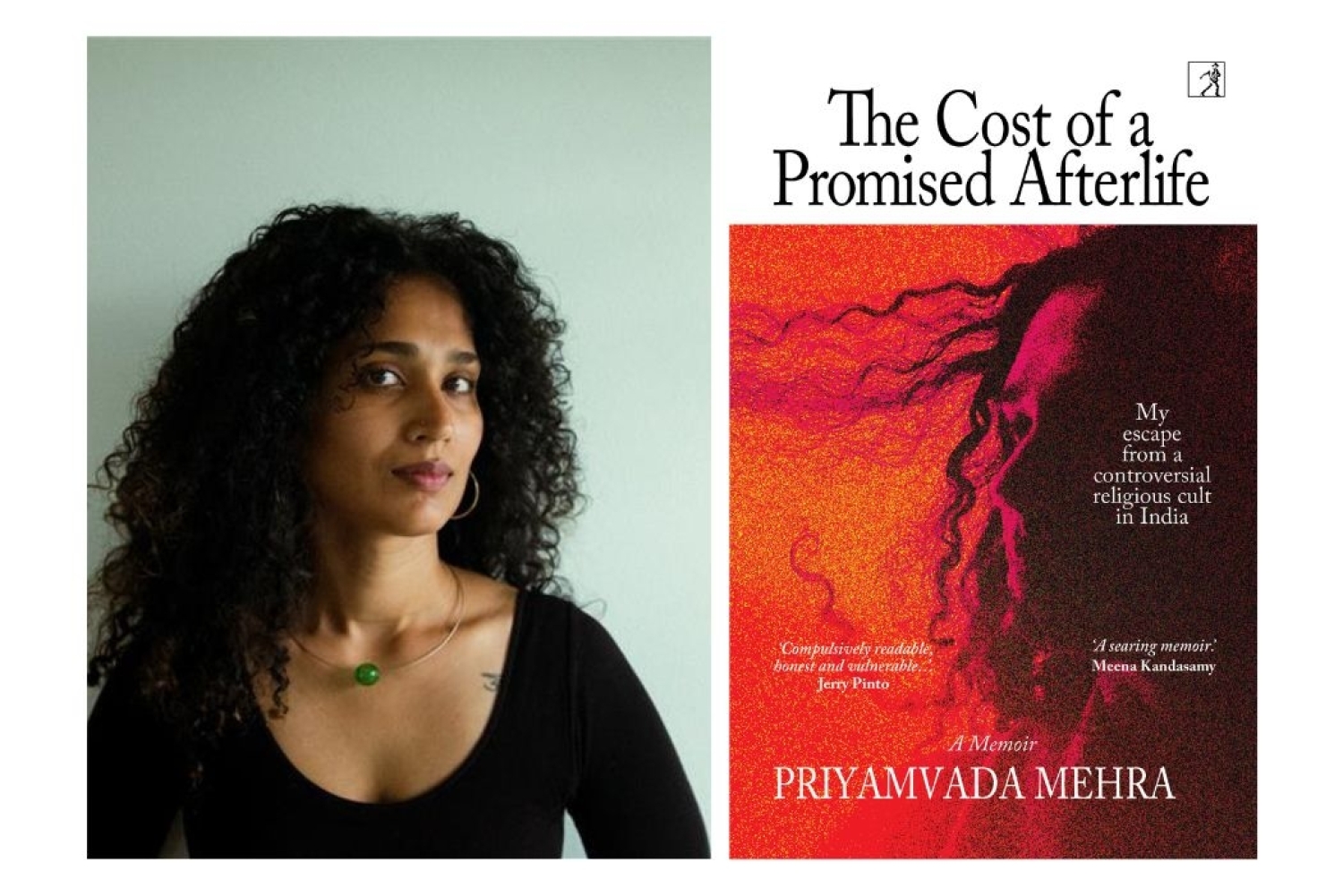

After moving to Europe in 2022, Priyamvada Mehra failed to adapt and function as what one would call a ‘normal adult.’ That failure pushed her to look inward, and that introspection led her straight back to her past, something she thought she had left behind. To make sense of what she was feeling, she started reading everything she could: books, memoirs, research papers, anything that would bring her closer to understanding her own experiences and help her name them. Somewhere in that process, she also began pouring her memories out on paper. It felt like a flash flood, and was overwhelming, intense, and unstoppable. Before she knew it, she was looking at a few hundred pages of what she called ‘angry notes.’ That’s when it struck her that maybe this was a story. Which is to say, the memoir wasn’t planned; it was born out of an excruciating introspection, a journey she was forced to take in order to move forward in her life.

When she realised that a story of this nature had possibly never been told before by a fellow Indian, in her country of over 1.4 billion people, her India, at first, she was surprised at first, and then she wasn’t. She wasn’t because it didn’t take her long to realise that the twisted privilege she had been bestowed, the privilege to reflect, is rare for people in her country. ‘Where is the time for the marginalised to sit down, to rest? Where is the chance for them to realise that, their whole lives, they’ve been at the receiving end of the politics of systemic oppression, of which religious cults are a significant part?’

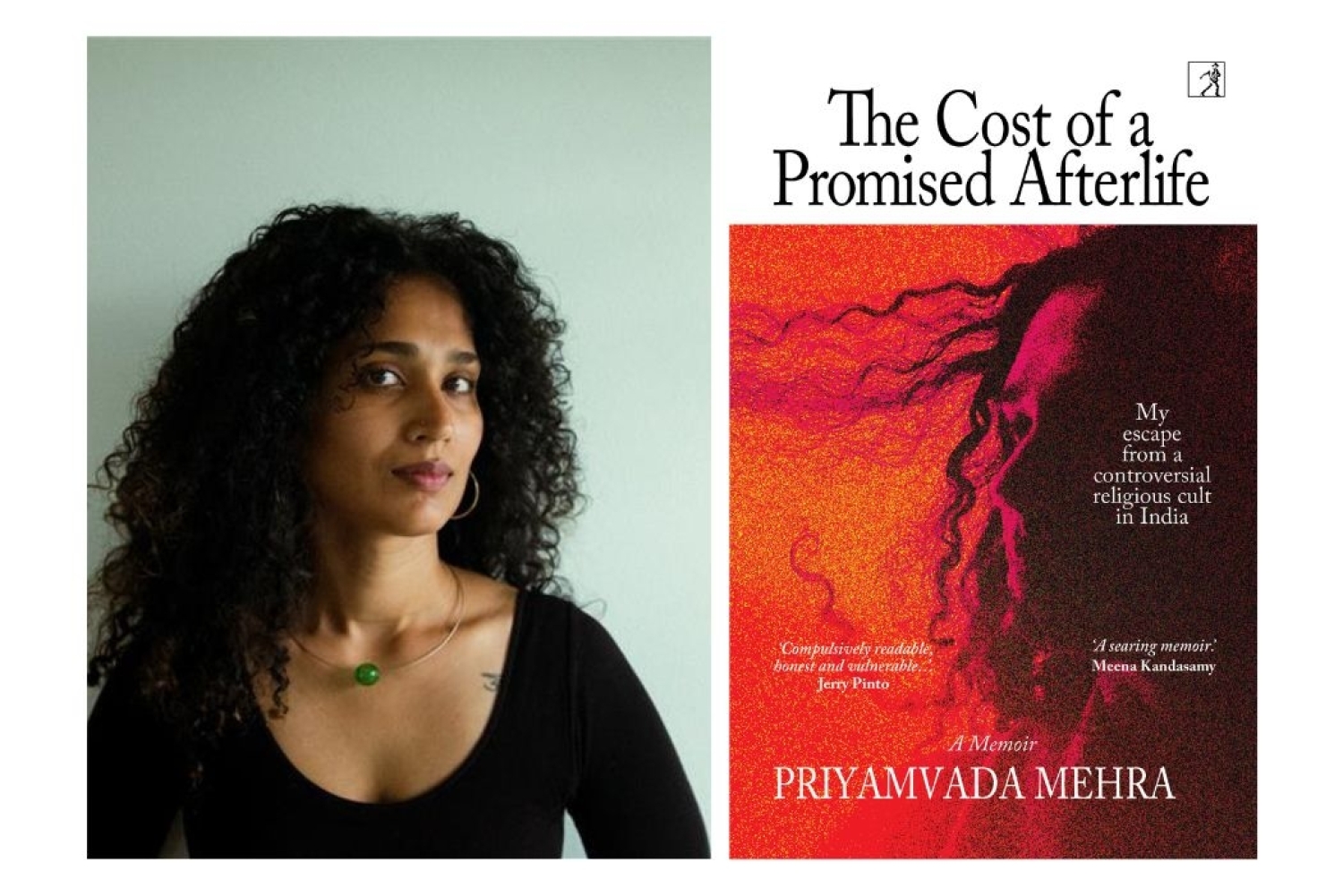

This conversation with Priyamvada Mehra delves deeper into The Cost of a Promised Afterlife and the journey that shaped it.

Could you tell us a little about the writing and research process, since the book covers such personal experiences, given that belief was deeply intertwined with your upbringing?

I tried finding people in India with similar experiences but couldn’t find any, or any literature on it, barring some investigative work. The only memoirs or academic writings on cults I came across were mostly by Westerners, especially Americans. The first book I read while coming to terms with my reality was Take Back Your Life: Recovering from Cults and Abusive Relationships by Janja Lalich and Madeleine Tobias. It gave me a language I didn’t have. It laid out the anatomy of a cult, the profile of a cult leader and the long-term psychological damage of indoctrination and abusive relationships. It was a revelation. I hadn’t known I’d grown up in one. I hadn’t known the relationships I was still chasing were rooted in abuse. The book cracked something open. No one had ever educated me about cults. No one used that word, even in a country like India, supposedly the world’s spiritual centre, where hundreds of thousands of self-proclaimed godmen and godwomen command the devotion of desperate millions. It forced me to see the desperation we lived with. How broken people cling to anything that promises certainty, even if that certainty comes from a ten-year-old boy in saffron robes calling himself a divine messenger when he should be in school. Or from gurus protected by politicians, global celebrities and power. I returned to that book again and again. And from there, I kept reading: memoirs, survivor accounts, research papers, anything that brought me closer to understanding my own experiences. I studied cults and their generational impact, the quiet struggles of those with disabilities and illnesses and the heavy toll of caregiving. I uncovered the deep scars of caste and class and traced the violence born of gender and patriarchy. In this journey, I reshaped my bond with the very foundations of my life. I pieced my world back together through books. I found the vocabulary to be able to articulate my own experience.

The form of the memoir requires deep self-reflection and confrontation of painful experiences—how did you find clarity through the emotionally overwhelming process of remembering?

The long process of introspection and reflection, out of which my memoir was born, took me through all five stages of grief, perhaps even more. First, there was the initial shock and disbelief that that was actually my life, and that my entire family, our opportunities, our lives, had been systematically eroded by a godman who, even though incarcerated, continues to exert complete control. The realisation that I was the only one who had made it to the other side of the religious dogma, the only one seeing things critically, was both liberating and devastating.

Not just that, the realisation that I was at the receiving end of abuse and violence based on gender and caste sucked the soul out of my body. Abuse had been so thoroughly normalised for me for years.

Then came anger. I was enraged. Each memory ignited such a seething fury within me that I wanted to claw my way back through time to throw the punches I never got to land. That’s when I began purging it all out on paper. All my traumas surfaced the way they did. I sought therapy for the first time in my life and was soon diagnosed with Complex PTSD. I continued to confuse scraps for love. I continued looking for empathy in the wrong places, in the wrong people. I kept hoping they would understand my pain, not realising that they were, unfortunately, the source of it. It took tons of emotional labour, therapy, physical as well as psychological safety, before I could finally see clearly and muster the strength to break free from the chains of fear that had bound me for so long. It’s hard to put into words how excruciating the entire process was. There were times I felt I was losing my mind. But I learned to take pauses when my mind and body signalled me to, returning after a week, or a month, or more, when my gut prompted me. Holding my book in my hands now gives me a sense of catharsis. It’s an acceptance of the reality of my loss. The loss of my family, the loss of my childhood, the loss of my time. And at the same time, I feel such a deep sense of boundless hope, not just for myself, but for others too, who may find themselves in similar situations in their own lives.

“Holding my book in my hands now gives me a sense of catharsis. It’s an acceptance of the reality of my loss. The loss of my family, the loss of my childhood, the loss of my time. And at the same time, I feel such a deep sense of boundless hope, not just for myself, but for others too, who may find themselves in similar situations in their own lives.”

How did you approach writing about your family, given their role in both your entry into and exit from this world of blind devotion?

Reading Terror, Love and Brainwashing by Alexandra Stein, I had underlined a line that stayed with me: ‘Almost anyone, given the right set of circumstances, can be radically manipulated into otherwise incomprehensible and often dangerous acts.’ It was true. The timing was cruel. My parents found the cult when they were at their most vulnerable. Only then did I begin to fully understand how religious extremism had shaped my family, and shaped me. It wasn’t just about belief. It was tied to my parents’ disabilities, their chronic illnesses, the weight of caste and class, the pressures of marriage and the desperation of parenting in scarcity. All these struggles didn’t exist in silos, they fed each other, creating the perfect storm. And in that storm, a godman found his grip.

Throughout my childhood and beyond, I inherited their fears, their traumas and their hopes for salvation. They passed it on unknowingly. And I, unwilling and unknowing, carried the cost. It was only now that I was beginning to realize the weight of that inheritance.

Therefore I have made a sincere effort to write about my once beautiful, fun-loving family with both empathy and honesty, and to acknowledge the complexity of human beings and their choices, while not softening the harsh realities of the abuse and oppression I faced. Even though they see themselves as the chosen ones, I see them as victims of larger manipulative systems. If I could make one wish today, it would be to free my family of years of religious thought reform, and place them back in time when they accepted their reality, imperfect and flawed. Where they didn't chase idealised, problem free lives, but embraced life with authenticity, navigating it as best as they could. Where they refused anyone selling them the illusion of certainty. Where they were adults with autonomy, critical thinking and an ability to question authority. That's what the cult robbed them of.

What does faith mean to you now?

I have a complicated relationship with the word faith, especially in a religious or spiritual context. I do not adhere to any religious belief system. I am developing the practice to base my faith, in any context, on rationality. At the moment for me, faith, religion, and belief all boil down to two things, purpose and love. The truth is that my time on Earth, like everyone else’s, is limited, and I want to use that time to work on those two aspects.

My non-profit organization, Gentle Boys Club, offers me that purpose. My intention to achieve professional success while creating meaningful and urgent social change, no matter how big or small, gives me that sense of purpose.

And my little chosen family, and my friends, they are my lifelines. They have helped me become the most authentic, most vibrant version of myself. They are precious, and that is what love means to me, something that will continue to grow.

What do you hope for readers to take away from the book?

It took me two decades to realize that I was a victim of a religious cult in India. I continue to lose my family to one, and nothing hurts more. It took me years to realise that I was a victim of patriarchy, a victim of casteism, and of the violence that all these structures of oppression breed, all of it without any fault of mine. Unfortunately, that is what we call our ‘culture.’ The time I lost isn’t coming back. The family I lost isn’t coming back. The long-term psychological and physiological harm cannot be undone. I had to rebuild my life around it. My story, I believe, can raise awareness about religious cults in India. It can help girls and women truly stand up for themselves and create the beautiful lives they have never stopped dreaming of. My story can help start a dialogue about the rot of caste and patriarchy, in our own minds, in our families, in our homes, and in our society. My memoir offers a deep look into the social issues we remain willfully naive or ignorant about in India.

It takes you through an excruciating journey of my escape from a religious cult, but it is equally a story of hope, possibility, freedom, power, and the beauty of a girl’s rebellion. I have written this book for my nine-year-old self, whose wings were clipped before they had a chance to form. I wrote it for my sixteen-year-old self, who had only known how to exist in crippling fear. I wrote it for my twenty-four-year-old self, who was doing her best just to survive. And then, I thought of the millions of girls who are nine, sixteen, and twenty-four today, in India and elsewhere, abused, helpless, subservient, scared, yet still dreaming. I decided to take them along with me on this journey. And so, I wrote it for them too. Readers will take away inspiration, to take a deep look within, and an even deeper look around. This book will open people's eyes to their own truths and realities, and how they wish to navigate through them. What they choose to uphold, what they choose to change, and what they choose to let go.

Date 20-20-2025