A conservationist, traveler, architect, chef and photographer, Tara Lal’s life’s trajectory was not planned from day one. Born into the family that founded one of the most celebrated Indian homeware brands Good Earth, Tara was always drawn to design, graphics and architecture. She studied Art History and Architecture, but one morning, she found herself not convinced of the path she had chosen. This need to understand what really made her happy prompted her on a journey which led her to realize that all paths led to the forest. ‘When we were kids, our parents would throw us into the car and go to all these forests. And eventually I came back to the idea that that is where I was happiest. It was then that I started to explore getting more and more into nature and contribution. And I ended up doing a lot of field work in South Africa and in Botswana. In India, it wasn't easy. A science degree was needed to do any kind of field work. So the more they closed the doors on me, the more I was determined to work this out.’

Before getting a degree, she spent time on-ground and experienced the gravitas of hands-on work in the field. That changed her perspective. ‘I actually wanted to become a ranger. That's where I was going. However, I broke my knee and had to get surgery, which is how I ended up doing a Master's in Conservation Science at Imperial, and then that took its own trajectory forward.’

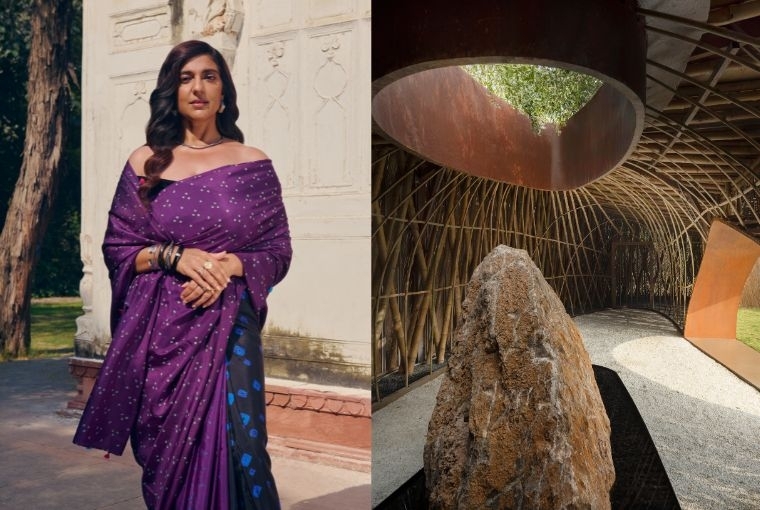

Her most recent project The Aranyani Pavilion, an installation and public arts initiative at Sunder Nursery, is an extension of her thoughts, experiences and understanding of the importance of conservation.

Can you tell us a little bit about The Aranyani Pavilion and what inspired it?

Aranyani is the goddess of the forest. She's the only goddess who has the Veda. This journey that I've had in conservation has brought me to many different places, and many ways of doing conservation. I've found that it's often very Western in its approach. I'm quite focused on what we call focus conservation. So it was about how we hold the land in and push the people out. But the more I got into it, the more I realized that that's not the solution. It includes people on the land in the solution and talking to them. We are sitting in an urban city doing our own thing, and then we want to give to people who are sitting on the land, which seems so unfair. So it's actually how we can support people the way they need to be supported to look after the land they've been looking after for years. And there's a whole other approach to that, because it's a far more feminine and emotional connection and approach. Some of that, mixed with my background in art actually came together to form Aranyani.

Who designed the installation? What did you have in mind? How did you merge the different disciplines of art, nature and society?

Through my journey, I have spent a lot of time in different sacred groves, and I found that sacred groves were actually cultural conservation areas. One of the things that I found in a lot of them is that you don't just walk into them. There's a path that takes you further in. And that path leads you very often to a stone shrine. And so there is a connection between you as a person entering, and feeling that sacred connection to the whole space. That's actually the inspiration behind making this pavilion. The path that you take, even in the pavilion, is mimicked through sacred geometry, where you actually walk into the pavilion in a circular path and then end up at the stone shrine. And that is also mimicked in the path within the journey inside us. The sacredness is the path within the forest, and is also the journey you take inside yourself. I worked on the concept with our architects, who are from TM Space, Tanil Raif and Mario Serrano Puche.

Aranyani is a large-scale installation that is extremely immersive. What went into deciding on the material?

That is something that I put a lot of thought into because of exactly that reason. The structure is in bamboo, and the rest of it is being made with upcycled lantana. Lantana is an invasive species that was brought by the British and the French in the eighteenth century. And it's actually invasive, so it's eating up a lot of our natural ecological landscape. We have to cut it down to allow our natural fauna and flora to grow. Part of the problem with this lantana is that once you cut it down, what do you do with it? And that's the part that we wanted to show here, is that you can use it for building, for furniture, or other things.

Sounds fascinating. I am curious to know, when it comes to the environment, what do you feel is the biggest threat that we are going to face? And how can we solve this problem together as a community for the future, for humanity, for our kids?

I think biodiversity loss is our biggest problem. Ninety per cent of the insects have disappeared in a lot of tropical areas. Due to that, what happens is that the animal that eats an insect disappears as well, and then eventually that affects our water table, affects our climate, affects everything. My PhD focused on behaviour change. We need to change the behaviour of people to be part of the solution. We must touch them emotionally. Data and information don't change people's behaviour; it's actually when you connect emotionally that's when people change their behaviour. We must work on connecting back to nature, and people need to spend more time amidst nature as only then will they want to protect it. In my opinion, every human being on the planet is a conservationist and should be one. I always say it's the food you eat, it's the coffee you drink, it's how you get to work. All of it is part of whether you live consciously. Not to put pressure on people that you can't do things, but to just think for a moment that everything you do is part of the problem, as well as part of the solution eventually.

What is a good start, especially for the youth?

I think we should get out into nature and connect them that way. There's so much information, and studying doesn't give that kind of feeling of using your hands, spending time. There’s this wonderful author called Robin Kimmerer, but she's written a book called Braiding Sweetgrass. She comes from a Native American community, and hearing her talk about having spaces where we just have people engage in nature again, you know, pick berries, sit under trees, actually go back to older times, because then you feel more connected. That's what made me actually want to also protect our nature and our natural heritage. So I think for me, that's more important in schools than just cramming more information.

Lastly, in your curatorial note, you said something about hope and keeping us whole. What gives you hope and keeps you whole?

You know, when I meet people who are on the ground and they truly believe in what they are doing there, I mean, it gives me so much hope to see the work that they are doing. That's what inspires me because in the most difficult circumstances, they are standing there at the front line really, of this fight. And they don't give up. That's why I think if they don't, we can't either.

Platform’s What’s Your Story featuring Ritwik Khanna, Nidhi Saxena, Ansh Kumar and Raghav Kumar will take place at The Aranyani Pavilion at 5pm today. RSVP here.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra

Date 9.2.2026