When a news channel or a newspaper reports an instance of conflict, it is often rendered down to stoic statistics. Much of conflict journalism speaks the language of numbers, a facade behind which much of the reality, much of the inhumanity hides. For Teresa Rehman, it is of utmost importance to tell that which is hidden and untold through her work in the field of conflict journalism, as she asserts in the first few pages of her new book, Bulletproof: ‘My focus in my work was to demystify the conflict, humanize it—to talk about the human helplessness and desperation.’

Rehman brilliantly does as she suggests she wants to, through her book. Bulletproof: A Journalist’s Notebook on Reporting Conflict is the story of a female combat journalist and her encounters with insurgency in Northeast India. Going beyond mere statistics, of deaths and arms recovered, and other documentary evidence, it shows us how conflict impacts women, children, health, environment, sanitation, wildlife and society. This book is a collection of rare human stories from one of the most under-reported regions in the world.

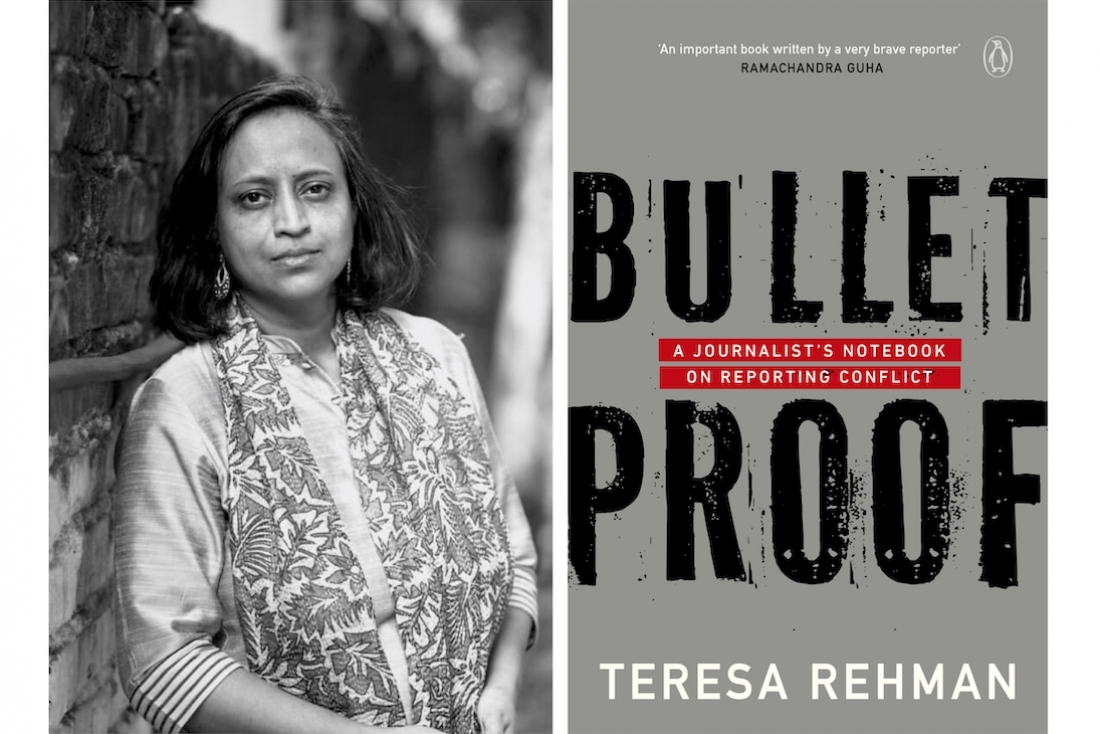

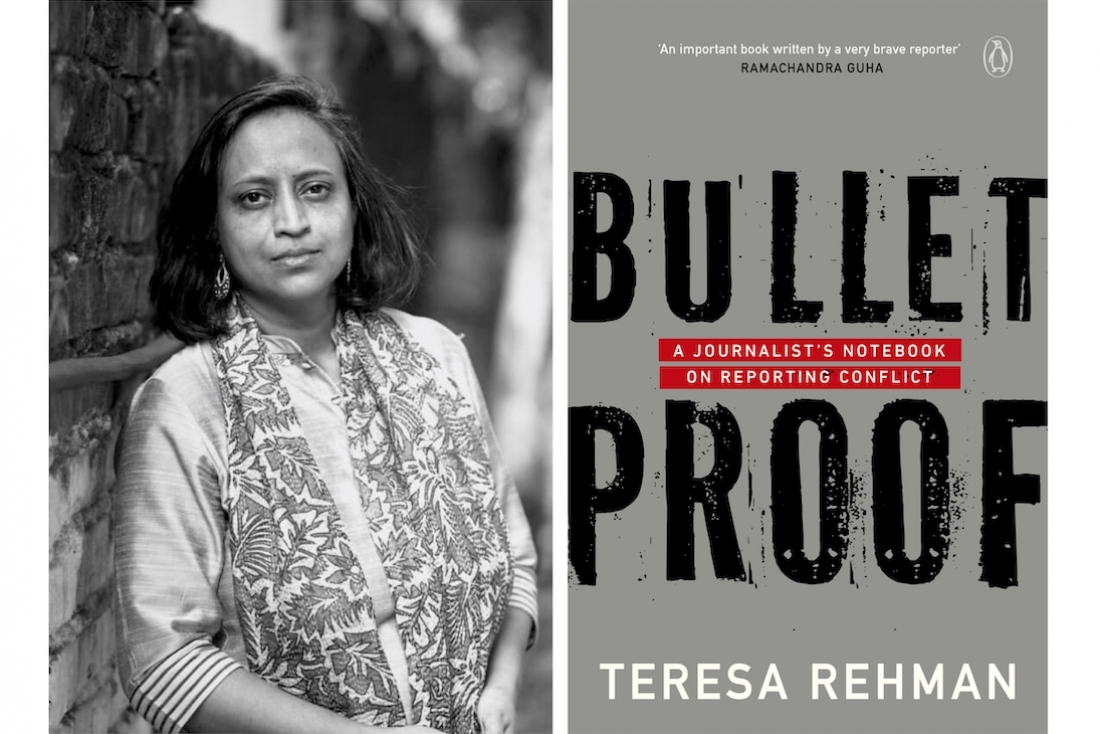

We connected with the writer to know more about her and her new book.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you ventured into the world of conflict reporting.

I would call myself a chronicler trying to tell the stories of men, women and children of Northeast India. As conflict is ingrained in the entire landscape of the region, a journalist cannot remain unscathed by it. Like me there are several generations who have grown up in the midst of violence, gory bloodshed and a chronic low-intensity war. The violence had changed many lives in different ways and convoluted many issues related to education and employment of youth, gender, children, wildlife etc. I have tried to delve deep into the issues and thus, conflict reporting became a natural corollary to my profession.

“I feel that it is pertinent to go beyond the hard statistics and tell the human stories waiting to be told.”

What inspired the writing of Bulletproof?

It is rare that one gets to listen to the travails of the person behind the stories – ie the journalist. I had long contemplated writing about my experiences on the field. The genesis of Bulletproof stems back to the year 2009 when at the first regional conference of the South Asian Women in Media (SAWM), senior journalist Munizae Jahangir asked me, “Do you wear a bulletproof jacket when you go reporting?” For a moment, I was flabbergasted. In my long innings of reporting from a conflict zone, I had never cared for my personal safety – both physical and mental. The question stayed with me. I kept pondering about my life as a journalist and hoped to write about my experiences when I walked on untrodden paths, armed with only a pen and a notepad. My former colleague Monideepa Choudhury told me, “In many ways, you are bulletproof.” Bulletproof is also the journey of countless journalists who work under tremendous duress in some of the most difficult terrains – geographical, political, social as well as cultural.

Could you take us behind the writing process of Bulletproof.

Writing Bulletproof has been both easy and difficult. It was easy because these stories were there within me. They were tucked somewhere deep inside my heart and in the pages of my crumpled notebooks. These were stories I never told anyone, not even to my colleagues, family and friends. Maybe, it was because I did not want to expose my frailties and vulnerabilities. So, it was difficult to be honest and pour my heart out to the world. In many ways, I am also a trendsetter of sorts, being the first journalist in the family. Therefore, this arduous journey as a regular combat journalist was mine alone. I felt it was important to tell my story as a journalist and a woman.

This is your second book and you’ve been a journalist for more than two decades. How would you define your relationship with writing?

I would rather call myself a reporter than a writer. And I feel that it is pertinent to go beyond the hard statistics and tell the human stories waiting to be told. I feel the region is a paradise for journalists and I relished telling the tales.

“There were many untold stories and I felt that as a journalist it was my duty to tell them. The challenges were manifold – there were no manuals to guide me. I was the lone wolf, stepping into the unknown with no modern safety equipment like a bulletproof jacket.”

In the Prologue you say, ‘My focus in my work was to demystify the conflict, humanize it—to talk about the human helplessness and desperation.’ How challenging has doing this been so far?

I was weary of the narrative emanating from the region. Conflict as reported in the mainstream media is very masculine -- full of stories of guns, artilleries, statistics of the number of people killed or injured. The real stories of the people are often swept under the carpet. There were many untold stories and I felt that as a journalist it was my duty to tell them. The challenges were manifold – there were no manuals to guide me. I was the lone wolf, stepping into the unknown with no modern safety equipment like a bulletproof jacket. Reporting conflict can spring surprises at every step. And my journalism school did not equip me with skills to face situations as they came my way. There are certain situations which a journalist would probably encounter once in a lifetime and there could be no precedents. There are many things that I learned along the way.

You speak at length about the dangers that a female conflict reporter faces and your own experience with PTSD. If you had to give advice to young women out there aspiring to carve a career in this field, what would you say?

I had always felt that one can only be a good journalist or a bad journalist. But, does the gender of a journalist really matter? Over the years I had realized that my gender came to play in the most unexpected ways. There are certain things peculiar to women and we often tend to overlook seemingly trivial issues like toilets, attire, personal safety etc. It is also a constant struggle juggling home and work, more so if the work calls for disappearing at unearthly hours and for days together. The world over, there have been incidents when women journalists have been killed, attacked, stalked or injured. And most importantly, there is no support system for a journalist reporting from this region – physical, legal and psychological. Personally, I had to undergo psychological counselling for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after doing a story on a fake encounter in Manipur. The aftermath of the story led to a civil uprising in Manipur and it was a harrowing experience for me. My mental state was aggravated by my physical condition as I was pregnant with my second child then.

I would urge young aspiring journalists to understand the socio-cultural milieu and the history of the region they are working in. It is important to start with the basics. In a conflict zone, it is equally important to be aware of the lurking dangers and taking care of their own safety – both physical and psychological. Reporting from a conflict zone has a fear factor that is real. A journalist has to face the wrath of both the state and the non-state actors. And incidents of newspaper offices being closed down, newspapers seized, and journalists abused, jailed and killed are living realities here. In fact, our media schools should incorporate a section on conflict reporting in their curriculum. Often textbooks don’t tell us the real picture and therefore, it is important for media students to interact with journalists working on the field.

Please tell us what’s next for you and if there are any other current projects that you are working on.

I am working on my next book trying to decode another aspect of northeast India, trying to tell yet another untold story.

Text Nidhi Verma