Photography Stephanie Macias Gibson

Photography Stephanie Macias Gibson

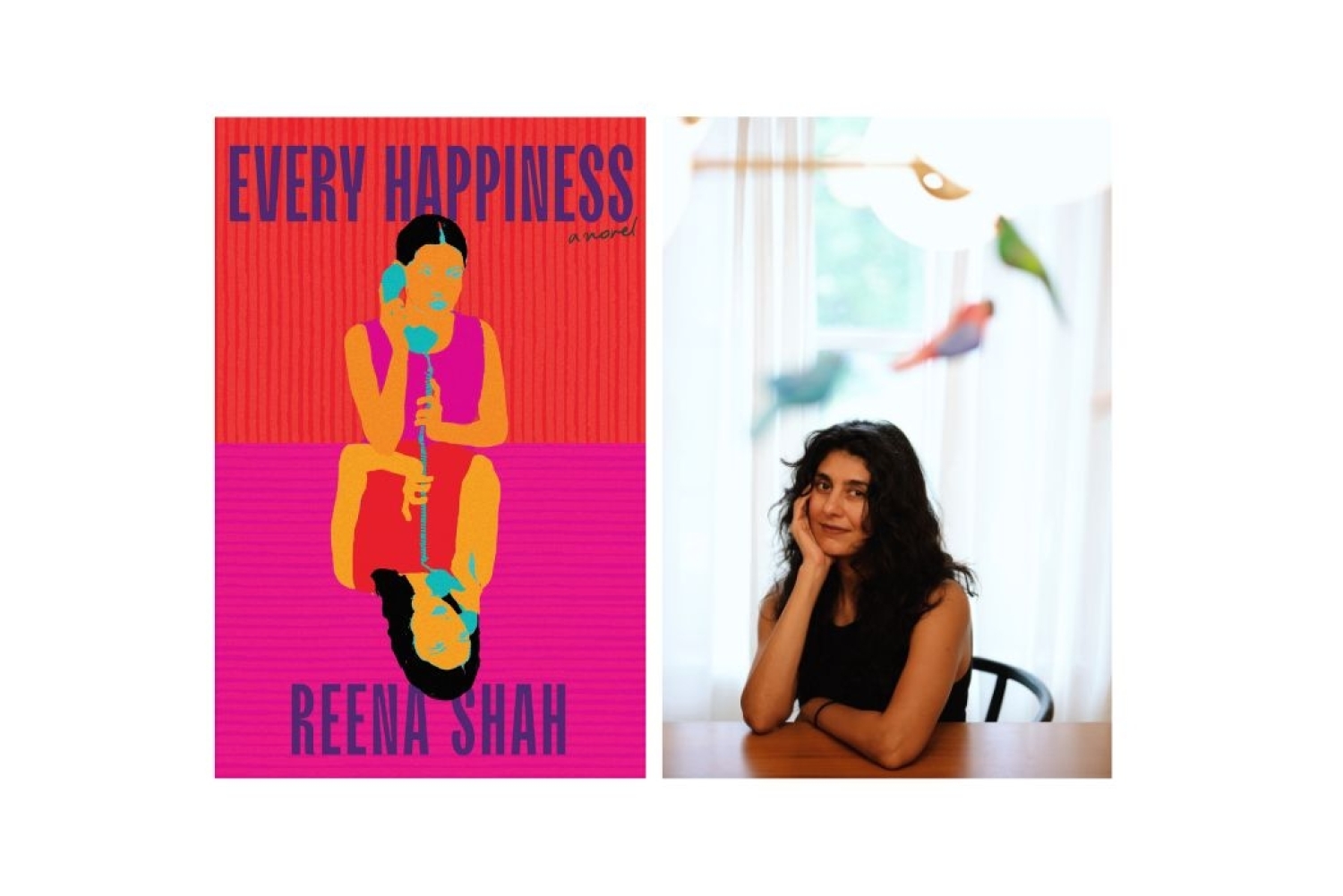

Every Happiness by Reena Shah traces the lifelong bond between two women whose friendship is shaped by desire, rivalry, migration, and motherhood. The novel begins in 1960s Mumbai, where Deepa and Ruchi meet as twelve-year-olds at their Catholic school. Their connection is immediate and lasting, marked by intimacy, jealousy, and feelings they struggle to name. As they grow up within families that expect obedience and achievement, both girls begin to imagine that fulfilling those expectations will bring them freedom, which is not exactly what it does.

The book first took shape as a short story set at a beach house party in Connecticut. Over time, that story expanded, and the relationship between Deepa and Ruchi moved to the center. Rather than casting one woman as a villain and the other as a victim, the novel allows both to be flawed and afraid, loving and resentful. We’re in conversation with Reena about how the story for this novel found her, the writing process, and narratives of the Indian American community in fiction.

How did the story for this book find you? Take us back to the roots of the idea behind this novel.

This book started with a single image of a young boy I met while working for an education organization in Mumbai. The boy was born with significant facial differences, and I learned that his parents, who were from a conservative, working class community, had to fight to keep him when they found out about his condition in utero. The image of this child and his mother stayed with me, and eventually the characters of Moksh and Ruchi emerged. I imagined Moksh as being unwilling to play the role of striving student, and Ruchi consumed with both worry for him and envy for other, more successful families.

What made you want to situate your debut novel around the ups and downs of female friendship?

At first, this wasn’t a novel at all, or about friendship. Every Happiness began as a short story called The Jains’ Annual Beach House Picnic that I wrote in 2018. It was told from multiple points of view and took place at a beach house party in Connecticut, which is now one of several party scenes in the novel. Deepa was more of a foil for Ruchi, and a far less developed character. With that story, I won my first artist residency to the Cuttyhunk Island Residency off the coast of Massachusetts. In the morning workshop, after the other participants went around and praised the story, the instructor took it apart and said that the story was overstuffed. It wasn’t a short story. I was gutted, but he was right.

He also said, ‘Deepa is not a villain,’ and that stuck with me. She may be spiteful and cruel and judgmental, but she’s also human, she’s also scared. I realized that part of me wanted Deepa to be a villain so I could lay Ruchi’s pain and problems at her feet. Once I stopped trying to push this narrative on Deepa, the relationship between her and Ruchi deepened and became the center of Every Happiness. I learned that a lot of emotions can reside inside friendship. For their whole lives, these two women keep coming back to each other, and every time they do, they bring with them their thwarted ambitions, their pettiness, their loneliness, their repressed desires, and also their love.

What was your writing process, and your approach to writing about the conflicting needs of a family and the self?

The early drafts of the book were more episodic. It took me a long time to learn to write chapters instead of stories. I’d already written hundreds of pages when Ruchi and Deepa’s relationship became central to the novel, and so many of those pages I threw out and rewrote. I think both women are pushing up against what’s expected of them, first as Catholic school girls in 1960s Mumbai growing up in families that struggle in different ways, and later as young wives who immigrate with their husbands to Connecticut. Both Ruchi and Deepa create fantasies out of these expectations. They imagine that if they fulfill what’s expected of them, they can find success and freedom, which will help them be themselves. It doesn’t quite work out like that.

Since the novel also follows both the lead characters’ tussles with motherhood, what drew you to explore their contrasting relationships with their children?

I wanted to write fiction for a long time and failed to. I was afraid of rejection, I think, and kept putting it off. I was also a kathak dancer, a north Indian classical dancer, for many years, and I wrote a biography about one of the form’s top disciples, Kumudini Lakhia. Then I had kids and my time disappeared and I thought, ‘I’ll write now that I’m exhausted and can only do things in 15 minute intervals.’ I’m not sure what it was about motherhood that made me write stories—maybe giving birth is a reminder of mortality—but I do think having less time helped me focus. My writing life has grown alongside my kids and while balancing writing with working full-time and family is hard, it also keeps me from being too precious about anything.

Ruchi and Deepa experience something very different as mothers. Their children become a canvas for their ambitions and failures. I wonder what it would’ve been like if motherhood were more of a choice for them, or if they knew themselves better. I wonder what it would’ve been like if they weren’t so lonely in Connecticut, or if they’d felt free to explore their sexuality. I wonder this for their mothers, too, and probably their grandmothers. But I do think that Ruchi and Deepa’s children, Moksh and Anu, get to have a chance to break the cycle of repression. It was important to me that they had the final word.

How did setting the story within an Indian American community shape the narrative?

I'm a first generation American, one of the first members of my family to be born in the United States, and that experience has certainly influenced Every Happiness. Deepa and Ruchi immigrated to the United States through their husbands’ work visas in the early 1970s, soon after the 1965 immigration act. They are among the privileged few who enter through the skilled worker quotas, and both my parents also came to the United States this way. I have photos of my parents on their departure days at the Mumbai airport, wreathed in garlands and flanked by every member of their family. It was an opportunity available to a narrow segment of society, those already privileged by caste and education, and it came with great expectations.

It’s a powerful thing, to leave home and move to a place where one hopes life will be different, better. It’s also incredibly disorienting. Wanting, needing, to belong and not feel like an outsider while also trying to hold onto the past, to culture and tradition that become more valuable when they aren’t readily accessible. In Connecticut in the 70s and 80s, the South Asian community was smaller than it was in Queens or New Jersey, and I think a narrow idea emerged of what it meant to be South Asian American at the time. In the novel, both Ruchi and Deepa search for community, and they also worry about what that community will think of them. The community offers protection, but it also creates limitations. No community is a monolith, but it can feel like one, especially for people struggling to belong. In Every Happiness, all the characters are trying to fulfill or subvert expectations from lots of different places, including the South Asian American community that grows in Connecticut over the course of the novel.

What are you working on currently, and what’s next?

I have a collection of short stories, Bad Neighbors, that will be out in 2027. It focuses on coming-of-age at every age. I think of all 12 stories as love stories in the most kaleidoscopic sense: romantic, filial, between siblings, between friends, resentful love, generous love, love that doesn’t show itself, and love that shows itself too strongly.

I’m also playing around with a second novel, though it’s too soon to describe what it’s about. Right now, it involves a questionable spiritual guru, a pair of 40-something year old siblings at odds with one another, and the history of Roosevelt Island where I currently live. But much of that might, and probably will, change as the characters lead me elsewhere.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 17.2.2026