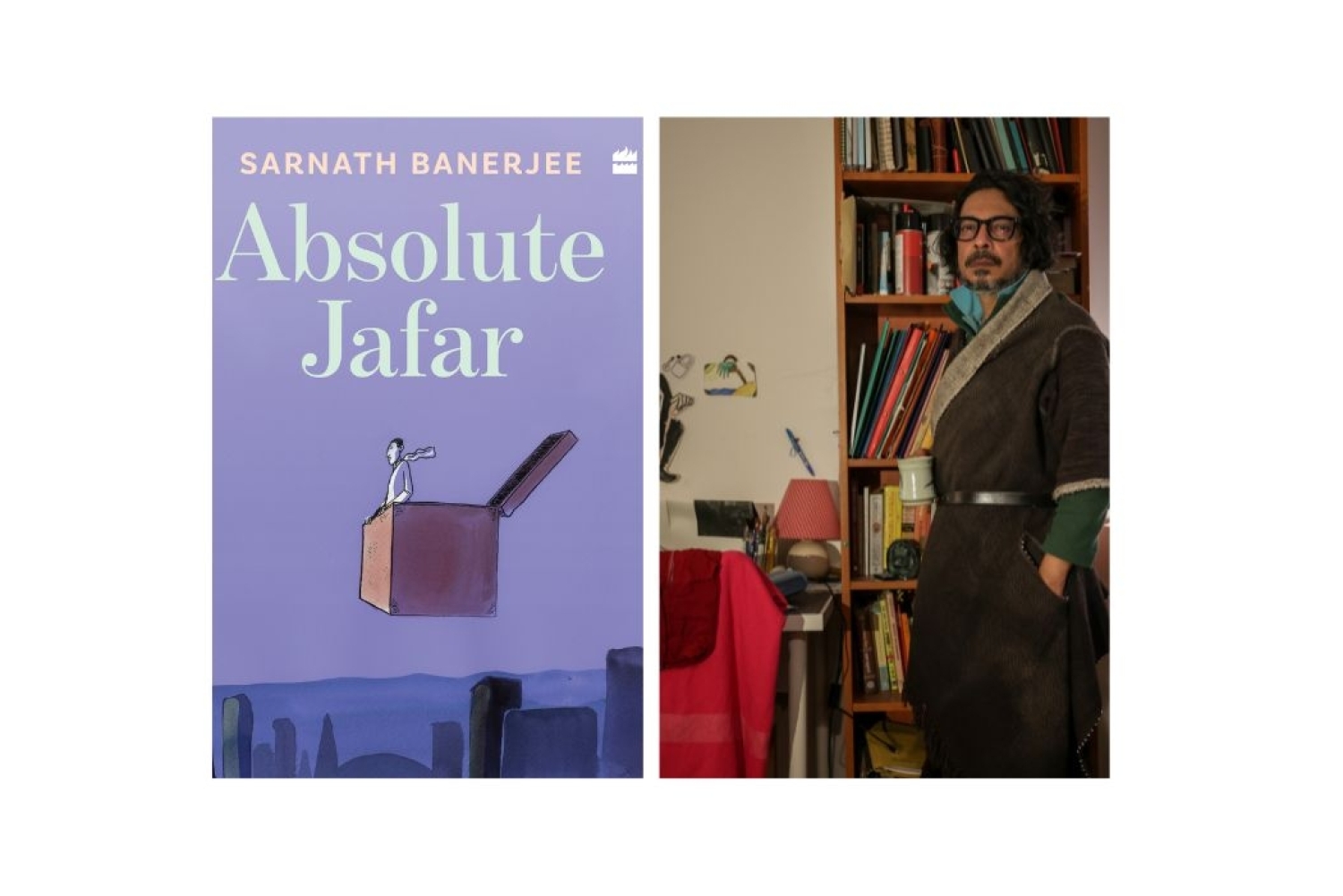

Can you tell us a little about your upcoming novel - Absolute Jafar. What inspired it and what research went into creating it?

After four years of enduring the bureaucracy of a cross-border marriage, we left our home in Delhi for Berlin in 2010. After briefly considering Colombo and Kathmandu, we ended up there, not so much for its thrills but more for seeking a peaceful home and a few years’ break before returning. Berlin was nice enough, but with time, it felt like a cultural Siberia. We had no context. I felt like being a native informer, constantly explaining my specificities to a clueless audience whose idea of the sub-continent, if any, was a series of stereotypes. We realised how provincial Europe was and how it can only understand things on its own terms.

The book was born of a need to record two decades of that life. A life that spans three cities - Delhi, Karachi and Berlin. It was like writing down the emotional history of an age. The narrative recounts micro-encounters that complicate the dominant mythologies surrounding migration, the self-serving lies we tell each other. It reveals a collisional world of clashing specificities, global and local misunderstandings, narrow definitions of identity politics and the rise of right-wing politics. Using shifting gazes - from European to non-European, diaspora to fresh arrivals, migrants to expats, the book challenges the notion of cosmopolitanism, multiculturalism and integration.

The book is also a quiet tale of a father telling bedtime stories to his Indo-Pak child in a tragi-comic attempt to hold on to the fantasies of a fading home, of sultans and jinn’s, of street food and eccentric family members, the local universes that he has left behind.

The father does it to deal with his own dislocation, but it turns out to be a doomed enterprise. The child is neither Indian nor Pakistani but a Berliner. Apart from desi food cooked at home, the mandatory three-week vacations during Diwali and Muharram, and an occasional wedding, he is very much his own person, with his own set of hybrid particularities. For him, Heimat is a small neighbourhood in southeast Berlin, not the sub-continent of his parents’ imagination.

“To remember is to reclaim memories. It might take you to very dark places. You feel every scene you draw. Fiction writers are keepers of time.”

It truly sounds extremely large in terms of story landscape. Harper Collins says it’s your most ambitious work yet – can you elaborate?

Certainly, in terms of scale and breadth, it isn’t something that I have attempted before. Plus, the story is very personal. To write a book like this, one must go through a great deal of remembering. To remember is to reclaim memories. It might take you to very dark places. You feel every scene you draw. Fiction writers are keepers of time. Writing this book was like going back twenty years and reimaging how a particular time felt. However, Absolute Jafar is not a work of nostalgia; it does not lament the past, merely pieces it together as objectively or as unreliably as one can.

The world has changed drastically in the last two decades if we talk about present time – what stories do you wish to tell and what stories engage you?

Social media has been a game-changer. Instant gratification and narcissism. You are the sum-total of the number of likes you get. This has a strange effect on creators. Works are valued for their meme-ability. Creators get sucked into providing what their followers want. The viewer, on the other hand, goes for the lowest-hanging fruit, the most available, most distributed option. Things have to be processed and spoon-fed.

When we started, long-form literary comics was a small enterprise. It was fiercely independent. Then came a phase when we wanted to become mainstream. Luckily, Chetan and Amish cured us of that illness, and we went back to our “widely read in a narrow circle” mode. But with social media, we are back to talking about reach and distribution. Sure, you want many people to read your work, but that comes with a cost.

In the late 90s, we wanted to create an Indian graphic novel shelf in Indian bookshops. For a short period, it looked as if we would achieve it. Now we have a graphic novel section in bookstores, but they are filled with manga and American graphic novels; the Indian graphic novels are usually out of stock. Whether it is the failure of the creators, the publishers, or the neo-colonialism of a new westward-looking readership, needs to be figured out.

Recently, there has been another tribe of people on the horizon, the AI apologists. A group of techno-optimists who think that AI is going to revolutionise creativity. Which is why daylight robbery of Miyazaki’s work was acceptable to so many. It is a typical tech-bro way of thinking - efficiency. In one click, you can undermine decades of work to produce a cheap replica. Luckily, they haven’t yet understood that the final work is the least important component in an artistic process.

The stories that engage me are still rooted in the hyperlocal, in the fantasies of ordinary existence and the spoils of urban living. I still have a small support structure and hope to continue doing things my way as long as age, motor function and eyesight allow.

“The book is also a quiet tale of a father telling bedtime stories to his Indo-Pak child in a tragicomic attempt to hold on to the fantasies of a fading home.”

Lastly, what is the one rule you would break for your art?

Writers are a disreputable lot. They have deep ears and a big appetite and are ever ready to cannibalise your stories. You enter a friendship with them at your own risk. I am respectful of people’s privacy, but it’s always hard to let a good story go. Sometimes I break rules.

This article is from the January EZ. For more such stories, read the EZ here.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra

Date 26.1.2026