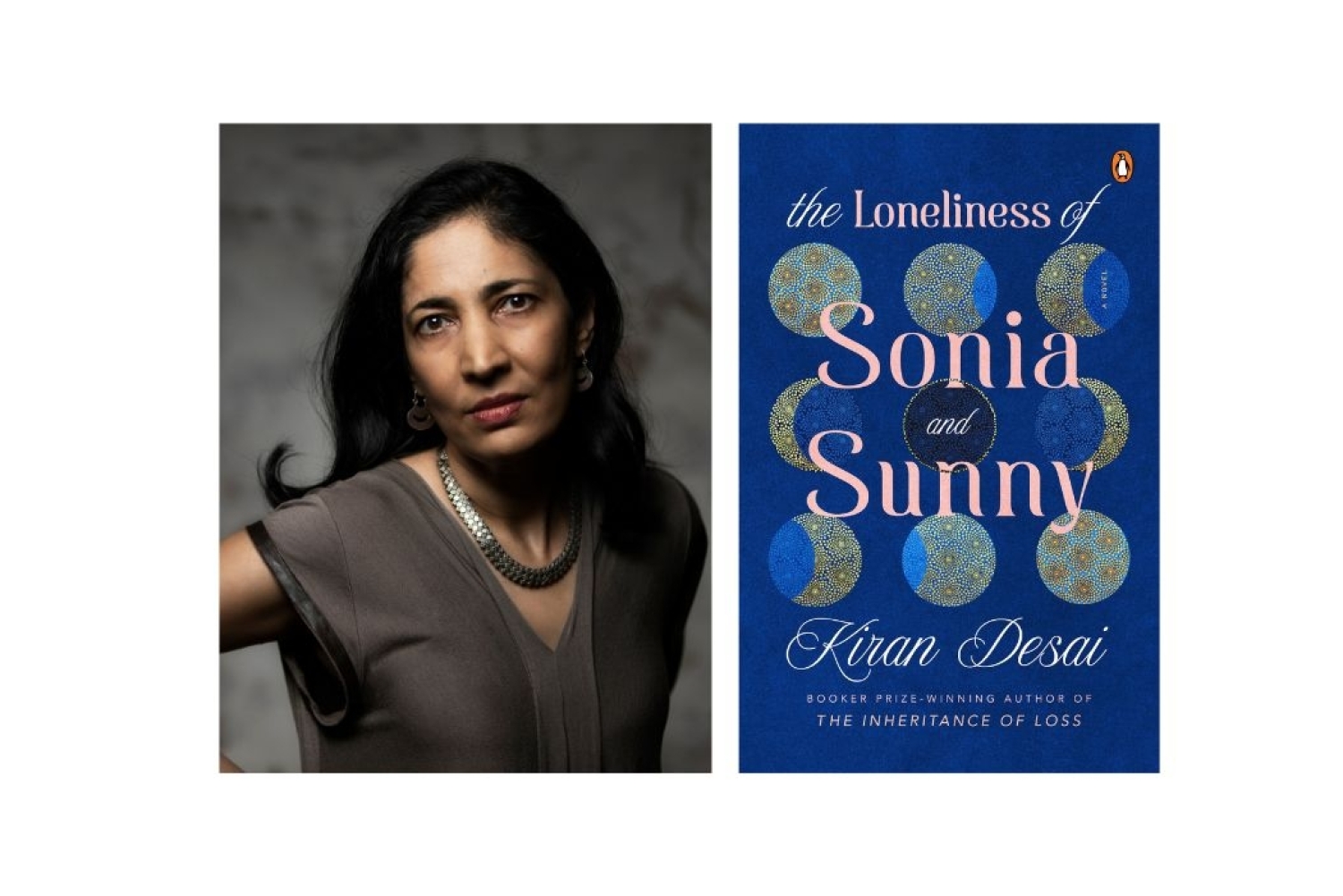

The art of writing about loneliness within fiction is a tricky one for every writer. How does one condense this vast emotion, with so many facets, into characters and plots? Kiran Desai might just have the answer. Her most recent novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, shortlisted for The Booker Prize 2025, was twenty years in the works before audiences got to lay their hands on it. This mighty achievement is a meditation on solitude, time, and the quiet ache of human connection. It bears the unmistakable patience and precision of a writer who has learned to find beauty in silence, and meaning in the solitary. Kiran gently dissected the ethos of her book for us, and gave us insight into her extensive world building process.

Congratulations on the longlist Booker. Your last book, The Inheritance of Loss won the Booker twenty years ago so the obvious question is, how come this long a wait for the next?

The last twenty years have been spent creating material; it wasn’t that I was thinking of writing this book when I first began. I was creating the material I would need to work into the future. I was keeping diaries, notebooks, following ideas wherever they went. At a certain point, perhaps five or seven years into writing, I read through all of that material and thought that I could make a book out of it, lifting certain themes and beginning to work on Sonia and Sunny. The idea for the title came at that time and that helped me focus when it came to whittling down the book from thousands of pages.

And what role did ‘artistic loneliness’ play in this large and ambitious novel?

Artistic loneliness came to me early in my first experiments with writing, which were very similar to Sonia in my book. I was a student in Vermont. I’d left India when I was sixteen, spent some years in high school and then went on to college. I spent many summers and winter holidays working in the library and began writing my first stories during that time. I felt both real loneliness—the painful kind of being away from home and alone for the first time—and artistic loneliness, the solace of being able to read and write in that silence, looking out onto a snowy landscape. It felt as exquisite as it was painful. That kind of loneliness has never gone away; it’s part of my discipline of writing now.

“I thought of loneliness as being as ubiquitous as water. The book has many ocean and water images. I thought of the different forms loneliness takes: the immigrant’s loneliness, the self-displacement of becoming unknowable. ”

In those moments in the university library, do you remember when the initial seeds of this book were sown? And why did you choose such elaborate, extensive world building—something not always seen in literary fiction?

After writing The Inheritance of Loss, which is a very political book about borders— whether in the Northeast or in the basement kitchens of New York—I think it gave me the courage to write from a more intimate sphere. At that time, I would never have been persuaded to write a love story. Although this book has a love story, it’s not exactly a romance; there are many other elements. Sonia and Sunny meet very rarely. I felt confident enough to go to this more intimate and vulnerable subject, to write about what two people may say to each other or about painful conversations such as parents deciding to part company. That feels revealing of oneself but it is also why we read.

When it comes to Indian stories, I’m often surprised at how books narrow down, especially those with love stories. I often think, where’s the family? In India, even in its absence, family is present. Dysfunctional, broken, divorced—it still takes form, it still exerts a psychological presence. I wanted to write about the stories that inform Sonia and Sunny’s story: the grandparents, the parents, all the different forms that love and marriage have taken in this landscape.

Yes, you have so many characters and side stories that help us understand Sonia and Sunny better. What kind of research went into it? How did you piece it all together?

I didn’t have to do actual research. I kept many diaries and journals. The places I picked were ones I knew. Delhi is my childhood. I was still going back while working on the Delhi chapters. Goa was also a landscape I wrote in, so the veranda where Sunny and Sonia sit, is familiar to me, though not in such a grand house. Italy came from brief but important visits. I wanted to write about a young couple abroad, about connections between countries that are not the West—what does it mean for an Indian to go to Mexico? I always loved reading Octavio Paz’s work on India.

For the characters, I had many and whittled them down to those connected to Sonia and Sunny. Many of them come across a kind of unknowing—a white, empty space I used as a psychological motif. Babita; when her uncles are murdered, Sonia; when she meets a man declared dead, Sunny; with the way news constantly changes form. Each character added to that lexicon. It was difficult to cut and rearrange; every time chapters came out, the whole book had to be reconstructed. Balancing themes with chronology— making the years and seasons add up—was the hardest part.

There is an enigma about Badal Baba, who recurs through the story. What is the significance?

Midway through writing, I worked on an introduction to the artist, Francesco Clemente. His Indian work is mystical, mingling shapes and forms, resembling what happens in your mind during a siesta, where real life and dream life mingle. One of his exhibitions was called Emblems of Transformation. It made me think about transformation in an age of nationalism and identity politics. Clemente’s work suggests we are always trying to escape identity; the narrative is never fixed. He gifted me a painting I loved, a little faceless demon that reminded me of tantric figures or monastery carvings. I realised I could use it as a talisman, a kind of deity in my book. I secretly structured the book around the question of who is captured by whose gaze—Sunny in his mother’s, Sonia in Ilan’s or in the gaze of a German sculptor. Badal Baba became central to that idea. The title speaks of the loneliness of Sonia and Sunny but all the characters have their own encounter with loneliness.

I thought of loneliness as being as ubiquitous as water. The book has many ocean and water images. I thought of the different forms loneliness takes: the immigrant’s loneliness, the self-displacement of becoming unknowable. Sonia’s father tells Sunny that at a certain age you wonder who you should have become instead of the person you are. There’s also loneliness as sustenance. Sonia and her mother find it a kind of peace, the quiet after war. There’s loneliness as luxury, as Albana tells Sonia—that true loneliness is a privilege of wealthy countries, while the real terror is the loneliness under surveillance in authoritarian states.

“In India, even in its absence, family is present. Dysfunctional, broken, divorced—it still takes form, it still exerts a psychological presence. I wanted to write about the stories that inform Sonia and Sunny’s story.”

Who are the writers you turn to for comfort and inspiration? What did you read during the process of this novel?

With Inheritance, I read Naipaul, Chinua Achebe, Mahfouz. For this book, I returned to books I loved earlier, even those I read in that Vermont library: Anna Karenina, Snow Country, a very Asian book though imbued with haiku principles, holding mystery at its heart. Kafka’s Castle, a metaphor for estrangement and the unending journey. Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being, another book about exile, borders and multiple couples. And finally, Love in the Time of Cholera, apolitical but beautiful; Marquez.

You have said the next novel won’t take twenty years. Do you already have something in mind?

I’m not sure which way I’ll go but I want to write more about Mexico, more about Satya and Pooja—the life of a rural Indian doctor in small-town America is very interesting to me. I’m also drawn to my German grandmother’s story, a mystery in our family. And I’d love to write a murder mystery, though I’m not sure I can. It won’t be a twenty-year novel again; I don’t have that much time now.

Words Shruti Kapur Malhotra & Neeraja Srinivasan

Photography M. Sharkey

This article is from Platform’s November 2025 Bookazine. For more such stories, purchase your copy here.